5.2 Examining the Intestines in an Autopsy – What to look for?

Autopsies are important to diagnose or verify Lawsonia intracellularis infections or to run a differential diagnosis in case of other enteric pathogens causing disease, especially regarding vaccine complaints.

In cases of diarrhoea, autopsy should be performed within 1–2 hours after death. A necropsy performed later than this may be a waste of time due to the early onset of autolysis. The small intestine lies in the right dorsal abdomen and extends to the floor of the abdomen. The large intestine is in the mid abdomen, with the blunt end of the caecum often on the floor of the abdomen near the umbilicus. The caecum extends along the left flank of the pig. The colon forms three double spiral coils in the ventral mesentery.

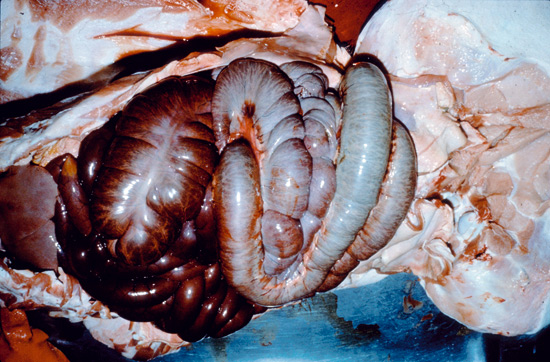

The first step after opening the abdomen of a dead pig is to palpate the root of the mesentery for any evidence of torsion. Intestinal torsions are common, important and usually fatal in finisher and adult pigs. They are sometimes called “haemorrhagic bowel syndrome”, but there is no inflammatory response involved in this condition. The severe reddening of the intestinal loops involved in the torsion results from passive congestion. With the pig lying in right-side-up position, with its legs facing the operator, the left hand, palm upturned, is slid under the caudal edge of the root of the mesentery, which normally forms a flat, smooth shelf. If there is any degree of mesenteric torsion, the root of the mesentery feels tight and cord-like; palpation indicates the direction and extent of the torsion (see pictures 5.2 a, b). Post mortem torsion may occur but no congestion or mesen-teric vasculation is present.

Picture 5.2 a (by J. Pohlenz)

Situs of a pig which died from a colonic torsion. Displacement of the large intestine resulting in severe bleeding into the intestinal lumen from venous congestion.

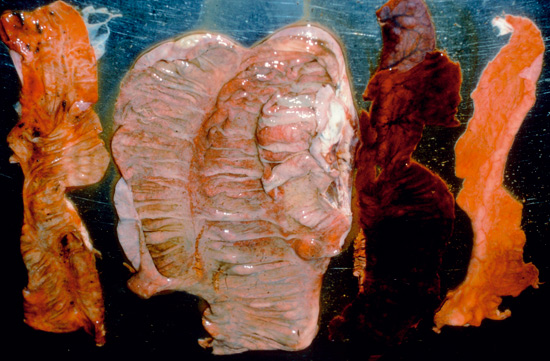

Picture 5.2 b (by J. Pohlenz)

Washed large intestinal wall from twisted colon. Blood coagulum in lumen, but neither inflammatory nor proliferative response.

After removal of the intestines from the carcass it is separated from its mesentery and spread out in its entire lengths on the table. The intestine is opened and its mucosal surface and contents carefully examined. Aggregated lymphoid nodules (Peyer’s patches) are present along the length of the small and large intestine. These patches are usually visible on the serosal surface as pale, circumscribed, slightly raised areas opposite the mesenteric attachment (see picture 5.2 c).

Picture 5.2 c (by J. Pohlenz)

Peyer’s Patch in a dilated blood filled small intestinal loop 450 cm behind the pylorus. This fattening pig exsanguinated from a bleeding stomach ulcer.

The wide continuous band of Peyer’s patch in the terminal ileum can give the contracted ileum a thickened appearance, even when normal. Peyer’s patches form a noticeable thickening of the mucosa around the ileocaecal opening often called the caecal tonsil. This is usually 2cm diameter, extending into the caecum and colon, sometimes tripod-like with a raised, pitted surface.

The small intestine, when contracted and free of contents, is normally off-white to beige in colour. Physiological congestion, the influx of blood into the intestinal tissue especially in response to eating produces colours ranging from pink to dark red. The colour of the intestinal contents may be off-white, light to dark red, sometimes brown, yellow or green. This may give the intestines a misleading appearance, especially when the small intestine is distended and its wall is thin, when the animal has been dead for some hours. Bile staining produces yellow to green duodenal and jejunal contents. The luminal contents vary from watery to pasty and normally contain food particles in the lower small intestine. The contents of the large intestine vary with the pig’s diet, but in general the contents of the caecum and proximal colon are soft, unformed, gritty, brown – grey to beige material. The beige colour of large intestinal contents is normally seen in free-range pigs and those fed on normal home mixed preparations. Many proprietary pig feeds have an excess of iron, which may alter the contents to a dark, brown colour.

© Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health GmbH, 2006

All rights reserved. No part of this Technical Manual 3.0 may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or photocopy, without permission in writing from Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health GmbH.