A snapshot of pig farming in rural India

Researchers have documented traditional farming practices and remedies in Nagaland, India in hopes of harnessing an underexplored resource.A recent article in the Indian Journal of Animal Sciences has explored the indigenous tribal knowledge of pig farmers in Nagaland, India. Since many of the management practices and remedies vary regionally and aren’t standardised, researchers hope to record, test and verify Naga tribal knowledge. This will allow Naga farmers, policymakers and scientists to coordinate efforts to improve productivity and preserve indigenous resources.

The importance of pig farming in Nagaland

Nagaland is a tribal state in Northeast India that borders Myanmar. The state is largely agrarian and backyard pig keeping is an integral part of Naga livelihoods and culture. Pigs account for more than 55 percent of the total livestock population in the area and the state has the highest per capita consumption of pork in India.

Pig farmers in Naga tend to use a cropping system to raise pigs. Since many producers do not have easy access to veterinary care, they rely on traditional management practices and indigenous tribal knowledge (ITK) to raise pigs. Producers are also dependent on locally available food and food waste to feed the pigs – commercial pig feed isn’t economical. Individual piggeries tend to be small and prioritise fattening over breeding, leading to low productivity measures.

The study

Though ITK is used widely to raise pigs in Nagaland, many of the practices haven’t been scientifically tested or recorded. Because of this, researchers wanted to document the Nagas’ pig farming knowledge and track the commonly used plants in pig farming. This would let researchers test the efficacy of the plants and make standardised dosing recommendations.

The researchers used surveys and case studies to collect data. After interviewing 165 farmers from different tribes in Nagaland, they tracked different aspects of pig husbandry. They focused on general management, feed, breeding and treating disease.

Key findings

Rural tribal farmers tended to have two or three pigs per household in open pens – very few producers let their pigs forage or scavenge. Piglets are weaned 2-3 months after farrowing. Since most pigs are raised for fattening instead of breeding, male pigs are castrated.

Since much of Nagaland is remote and rural, the availability, accessibility and affordability of high-quality pig feed is a major constraint on production. For the most part, conventional pig feed isn’t economical for small-scale farmers. Instead, Naga farmers developed a self-sustainable local resource system to feed their pigs. Researchers found that producers didn’t prioritise pigs’ nutritional needs when making feed. Pigs are fed local vegetation, crop residues and kitchen waste during grow-out.

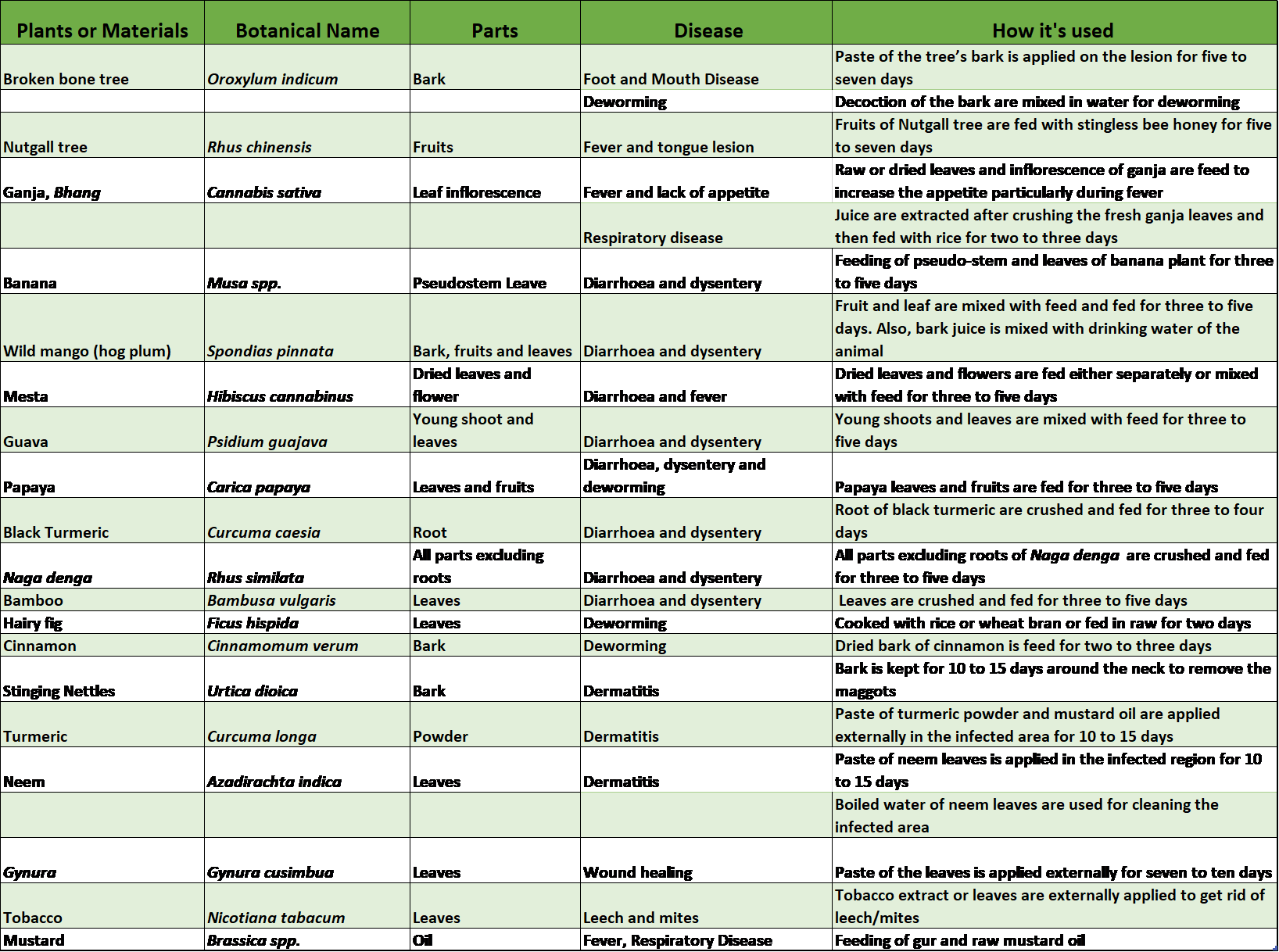

Farmers relied on ethno-veterinary plants and resources to treat most pig diseases. Diarrhoea, dysentery, classical swine fever, respiratory issues and foot and mouth disease are treated with locally available vegetation. The researchers noted that there were significant variations in doses across regions and tribes within Nagaland. Prescribed doses were determined by context and case-by-case factors – there weren’t any overarching or consistent guidelines for the remedies.

Tribal farmers' traditional knowledge and practices for pig farming in Nagaland - Scientific Figure on ResearchGate. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/f... [accessed 19 Dec, 2019]

When the researchers explored breeding strategies in Nagaland, abortifacients and breeding prevention techniques were common. Though rare, some tribes would cut the tip of the vulva in female pigs to prevent oestrus and breeding, and castrating male pigs was common. Similar to the disease management strategies, researchers noted that prescribed doses varied widely.

Conclusions

Indigenous tribal knowledge in pig farming is an underexplored resource. Many of the ethno-veterinary remedies observed by the researchers appeared to be effective, but additional research is needed to determine appropriate doses and make uniform recommendations. The researchers note that since many of the plants mentioned in the study are foraged from the wild and not cultivated, additional resources should be devoted to conservation efforts. This will allow Naga communities to preserve tribal farming practices.