What is the National ASF-surveillance plan?

The pork industry leans heavily on diagnostics to minimise the impact of disease, but they’re especially critical for monitoring African swine fever (ASF) and other trade-limiting foreign animal diseases (FADs).Key to that effort is the new ASF-surveillance plan, which ties into the already existing classical swine fever (CSF) surveillance programme directed by USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS). It is officially known as the swine haemorrhagic fevers: African and Classical swine fever Integrated Surveillance Plan.

‘Broaden our ability’

“It will broaden our ability to surveil for CSF as well,” Paul Sundberg, DVM, executive director of the Swine Health Information Center told Pig Health Today, making both programmes more efficient and cost-effective.

“We will test samples from the same high-risk animals, using the same overall process, but will test for both diseases instead of one,” said Greg Ibach, USDA undersecretary for marketing and regulatory programmes. “An enhanced surveillance programme will serve as an early warning system, helping us find any potential disease much more quickly.”

In the near term, the enhanced surveillance program will confirm the US herd’s ASF-free status to current trading partners. Long term, it will support efforts to restore trade markets and animal movements as quickly as possible should the disease be detected, Ibach added. Indeed, since there is no vaccine or treatment for ASF, the best defence is a quick response and containment.

Digging into the details

USDA’s timeline is to fully implement the combined surveillance program over the course of this spring. There is no pre-determined end date. “It’s an ongoing program, and we need it to be,” Sundberg said.

According to APHIS, the enhanced surveillance programme will test samples from high-risk animals, including submissions to veterinary diagnostic laboratories (VDLs); sick or dead pigs at points of collection, such as markets or packing plants; and pigs from herds at greater risk for disease such as exposure to feral swine or waste-feeding systems. USDA also will work with state and federal partners to identify sick or found-dead feral swine to determine if they should be tested for ASF or other FADs. Feral swine collected through hunting or trapping that appear healthy will not automatically be tested.

The key point is that surveillance samples will come from swine that are already raising health questions, because they provide a higher likelihood of detecting the disease. The VDLs will use real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing, which detects viral antigen, and therefore testing healthy pigs without clinical signs would provide little diagnostic value, APHIS cited.

More specifically, Dave Pyburn, DVM, National Pork Board’s senior vice president, science and technology, noted that for domestic pig samples to be eligible for ASF testing, one of the following clinical history categories and/or post-mortem lesions must be documented.

Clinical history:

- Increased mortality rate.

- Febrile conditions, including fever, lethargy, anorexia, depression, abortion.

- Undiagnosed central nervous system cases, especially congenital tremors and nonsuppurative encephalitis; also, lameness, recumbence, paddling.

- Haemorrhage, including red, blotchy skin (antemortem erythema, petechiae); hematoma; bleeding from the nose (epistaxis).

Post-mortem lesions:

- Hemorrhagic lymph nodes or organs.

- Enlarged spleen.

- Tonsils - erosions, hemorrhage, necrosis, proliferation.

- Gastrointestinal - acute or chronic ulcers, button ulcers.

“There will be some discretion by the lab diagnostician whether a sample meets the case definition and should be included in the surveillance programme,” Sundberg said. “If the case fits into the programme, USDA will pay for the CSF and ASF testing.”

It’s important to note that the programme document clarified that the ASF case definitions are a work in progress and subject to change as more information is collected through the sampling process.

Selecting samples and VDLs

APHIS has outlined that laboratory submissions from clinically-ill pigs that meet the ASF-testing criteria would use tissue (in order of preference) from the tonsils, spleen or lymph nodes. Submissions should reach the VDL within 48 hours - the sooner the better.

VDLs in the National Animal Health Laboratory Network are candidates to participate in the AS- surveillance programme, but they have to be certified by USDA. Due to capacity and location, not all laboratories may elect to participate.

“Rest assured that the major swine diagnostic labs will be contributing to the programme,” Pyburn said. “It’s a good bet that the CSF labs will serve as ASF labs.” There currently are 10 VDLs participating in the CSF programme.

The VDL tests will determine a negative or suspect result. “Any suspect result will have to be confirmed positive through additional testing at USDA/APHIS Foreign Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory (FADDL) on Plum Island,” Pyburn pointed out.

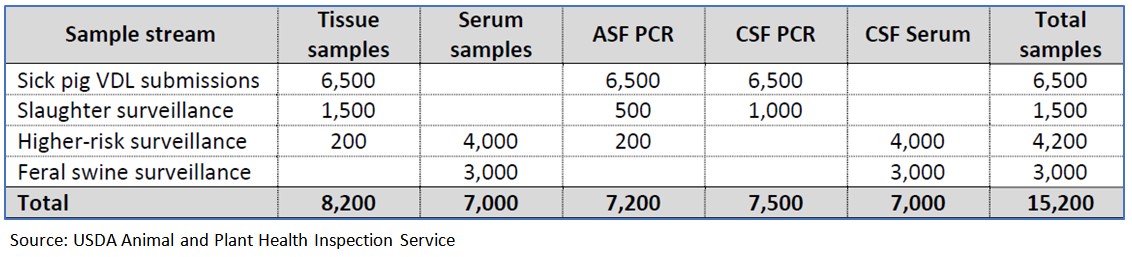

Sundberg said that the FADDL system is designed to ensure a quick turnaround on FAD results. The annual sample numbers by the various categories or streams as designated by USDA/APHIS are outlined as follows:

© USDA

Pyburn emphasised that it’s essential with “all diagnostic lab submissions to send in detailed and accurate clinical signs and descriptions of disease on the farm along with the premises identification number in order to help facilitate this surveillance programme.”

Real-world reporting

So, how would things unfold in the real world?

First, if there is a sincere suspicion of an FAD on a farm, the herd veterinarian will contact the state veterinarian or animal-health official before testing even begins. Out of caution, the state or federal official may place a stop order on all hog movements, until the VDL test is completed and confirms a negative status.

Beyond that, Sundberg offered this snapshot of how the surveillance program would proceed. Sick-pig samples are submitted to the VDL, and the diagnostician determines whether it is a case compatible for ASF. If the test results come back as “negative,” then hog movements and on-farm production can return to normal. If the results are “suspect,” additional samples will be collected and sent to FADDL for final confirmation.

“There is no public reporting until a test is confirmed positive through Plum Island,” he emphasised. “The test results are extremely accurate.”

This surveillance programme is meant to serve as something of a test run, evaluating the ability to handle high-volume sample collection in the field, VDL capacities and data management in the event of an actual ASF or CSF outbreak. Having consistent and timely surveillance data in hand also could help focus initial outbreak testing and response efforts.

According to APHIS, surveillance reports will be summarised quarterly and annually, and the overall program will be evaluated after the first year and then every 3 years.

Important to all

The CSF and ASF-surveillance programme is important to the FAD preparedness for all US pork producers and swine veterinarians whether you oversee one pig or 1 million. “It’s critical that anyone who has a dead pig or a mortality event of any size gets professional veterinary help and submits samples to get a diagnosis,” Sundberg said. “Never assume you know what you have.”

Diagnosing ASF, and CSF for that matter, is complicated because the clinical presentations resemble symptoms of many other production diseases already present in the US. The longer the delay, the more likely an FAD will spread. After all, there are more than 1 million hogs travelling on US roads every day.

Sundberg also emphasised that on-farm biosecurity is the last line of defence for the national herd. “Anyone that is lax, whether a small or large producer, can bring the whole country down,” he noted. “You are part of the national biosecurity.”

Now is the time to review on-farm biosecurity procedures with your herd veterinarian. There are plenty of resources, including PQA Plus and the Secure Pork Supply plan, both of which have user-friendly biosecurity checklists and materials.

In a final recommendation, Sundberg emphasised that farms do need to move a bit beyond the regular biosecurity plan and think about international contacts. This is not just about limiting international visitors but also knowing whether your employees have such interactions.

“You need to know and have protocols in place, including restrictions on bringing lunches on the farm,” he added. “We are really glad that USDA is implementing this surveillance programme. We have to do everything to protect the country.”