Is it time to eliminate PED from US herds?

Outbreaks of PED in the US were a wake up call but is it time time to take the next step and seriously consider eliminating PED from the national herd?

Porcine endemic diarrhoea (PED) virus made its way into the US swine population unexpectedly in 2013. That year at the World Pork Expo, Paul Yeske, DVM, of the Swine Vet Center, St Peter, Minnesota, and I led a meeting stressing the importance and value of elimination. We had little support because there were a lot of unanswered questions.

Nevertheless, PED was a great wakeup call for the industry. It spawned development of the Swine Health Information Center (SHIC) as well as a definition of transboundary agents. It fostered cooperation with USDA. The industry realised $3.734 million Pork Checkoff dollars for research. Elimination techniques were refined to minimise losses. Thousands of dollars were invested in biosecurity, including erection of truck washes. Research models were developed to evaluate our industry’s risk for entry of foreign animal diseases.

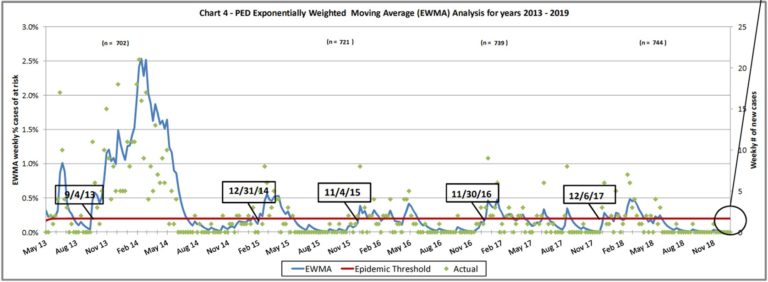

As a result of these efforts, the number of PED cases each winter in the Morrison Swine Health Monitoring Project database remains essentially the same (Figure 1). That might be considered progress, but I believe it’s time for our industry to take the next step and seriously consider eliminating PED from the national herd.

Back in 2013, I was confident we had a high probability of success based on experience with transmissible gastroenteritis (TGE) virus elimination as well as the resourcefulness of producers and veterinarians. I thought there was a higher likelihood of success if we moved before this pathogen became endemic. The experience with PED in our practice has demonstrated that some assumptions were correct and others not.

Correct assumptions

At my practice, we’ve learned that PED can be eliminated in individual herds with relative ease and with a 95 percent or higher success rate. Failures can be corrected in a timely manner, leading to 100 percent resolution.

Re-entry of the PED virus into a herd can’t be predicted, but it requires a coordinated sequence of events - a “perfect storm,” so to speak - and is therefore unlikely.

Elimination of any pathogen in the national herd is generally a good thing because it enables our industry to be globally competitive in costs and allows us to focus on other costly, endemic pathogens, such as porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) virus.

Our industry needs to improve biosecurity.

Incorrect assumptions

It was wrong to assume that PED management would be similar to managing TGE or that segregated production and external/internal biosecurity would prevent widespread movement of the virus. PED virus survivability is not similar to that for TGE.

Planned exposure with sanitation is inadequate as the basis for PED virus elimination in an individual herd. There is no smoking gun or single ingredient to explain PED.

Perhaps one of the biggest incorrect assumptions was that PED would not affect post-weaning performance, because it does.

What have we learned?

Contamination of herds with the PED virus through transport - at collection centers such as harvest plants, cull stations and transport centers - can occur, though at a low dose. Some of the procedures suggested for transporters and at collection points to prevent PED virus transmission were impractical.

The industry can’t build enough truck washes to physically wash all slaughter trucks without disrupting the flow of pigs.

PED virus can survive in stored manure, but good biosecurity practices minimise this as a contamination risk. PED virus can also survive in certain ingredients such as sodium metabisulfite, lysine, Vitamin D and plasma, and these ingredients may actually protect the pathogen.

Temperatures that can inactivate PRRS virus aren’t high enough to inactivate PED virus. However, feed and/or the risk of PED virus contamination in feed ingredients can be mitigated with high enough temperatures, with high temperatures plus storage for two weeks at room temperature or with chemical treatments.

Nursery, finishing and wean-to-finish facilities can be cleaned and decontaminated with basic procedures and processes.

Natural immunity against the PED virus is of relatively short duration, but it can lower pre-weaning losses if the herd is subsequently exposed. Killed vaccines, which are the only type of commercial vaccines available in the US for PED virus, provide some protection in previously exposed animals and can marginally lower pre-weaning mortality. We need a modified-live vaccine (MLV) and one that’s highly protective.

The inability to grow PED virus in the lab continues to impair diagnostics, particularly when monitoring sanitation processes.

Growing-pig performance is economically affected by PED but is often overlooked.

Growing gilts and sows stop shedding PED virus but it may take up to 12 weeks. The time it takes to stop shedding is shortened if gilts have two PED virus exposures.

Can PED virus be eliminated on a regional and national scale?

With the movement of pigs and sows on a daily basis, regional elimination is probably only possible in peripheral geographical areas, such as west of the Rockies, the Southwest, Arkansas and east of the Appalachians. All other areas will need to be part of the national programme. Canada is well on its way to elimination of PED from Manitoba and previously was successful in Ontario.

MLV vaccines for PED in the US would be a huge step forward.

Steps toward elimination from national herd

Eliminating PED from a herd requires commitment and leadership from the producer and a commitment from the herd veterinarian. Everyone else in the production chain, such as service providers, transporters, etc, must cooperate.

Herds with endemic PED virus need to be identified. There needs to be an individualised plan for PED virus elimination with a timeline that coincides with an industry goal for elimination. Replacement gilts must be exposed at 10 to 12 weeks of age and 18 to 22 weeks of age until 1 October, and after that date, exposure must cease.

We’re also going to need increased biocontainment and biosecurity in the nursery and in finishing or wean-to-finish systems and at collection points for one year. SHIC’s rapid-response team needs to be involved if an unexpected case occurs.

Producers need to be transparent about the PED status of their herds through the SHIC programme. We could also benefit by carefully reviewing Canada’s success eliminating PED.

In short, the US swine industry has the tools and technology to eliminate PED. We just need to put them to work.