What do we know about the 2018 ASF outbreaks?

With the recent surge in cases of African swine fever around the world, and its prevalence in Eastern Europe, stakeholders in the agricultural sector are keener than ever to gain a deeper insight into the causes, management and implications of these outbreaks.As the name indicates, African swine fever (ASF) originally comes from Africa, where it is endemic. It first appeared in Eastern Europe in Georgia in 2007, and from there the virus spread to Russia and other countries, reaching the European Union in 2014. Now, following the 2018 outbreak of ASF in Belgium, there is a pressing need to find the best measures for both preventing and controlling the disease.

Causes and clinical signs

Wageningen Bioveterinary Research describes the causes and symptoms of ASF as follows: ASF is a viral disease that only wild boars and domestic pigs are susceptible to. No vaccine against African swine fever is available. Research into the spread of ASF in Eastern Europe indicates that human intervention played a major role, which is suggested by the often large distances between outbreaks.

The virus spreads directly from animal to animal and indirectly through contaminated materials, biting flies and ticks (in which the virus multiplies). It is also easy for the virus to enter into the feed chain via food waste or offal from infected pigs. The diagram below shows how animals can become infected.

.jpg)

Infographic: how animals become infected (source: Wageningen Bioveterinary Research)

The incubation period for ASF varies from between two and 10 days, depending on the virulence of the virus. Laboratory tests are always essential to make a definitive diagnosis. Clinical symptoms may look similar to those of classical swine fever: fever, listless pigs, a lack of appetite, red skin, (bloody) diarrhoea, vomiting. Bleeding, cyanosis (blue skin) and necrosis of parts of the skin (blackening) may occur. Sows may abort upon infection. Pigs may suddenly die without symptoms being observed beforehand.

Domestic pigs can experience mortality of up to 100 percent, and 30 and 70 percent for lower mortality-rate strains. Pigs surviving the acute phase may remain carriers of the virus for several months; symptoms may disappear but can return at a later stage.

The virus may be found in sick animals in the blood, tonsils, lymph nodes, spleen and liver, among other places. Laboratory tests are always essential to make a definitive diagnosis.

The 2018 ASF outbreaks

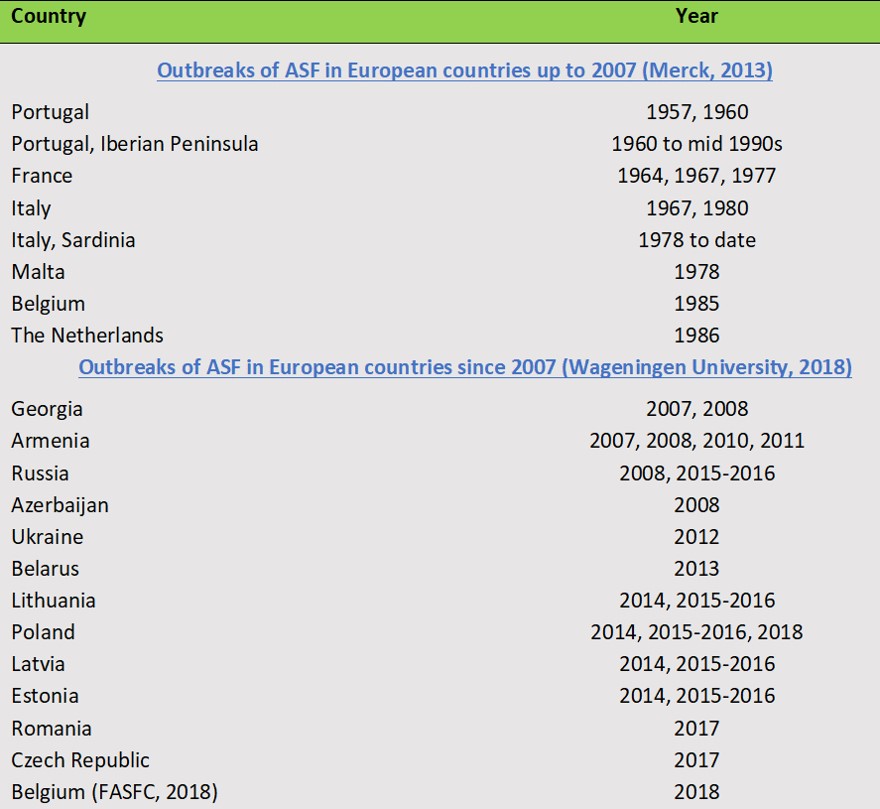

Sometimes the outbreaks can be understood by connecting the dots backwards. For example, analysis of the genetic background of the detected viruses has confirmed that ASF has spread from Russia to most of the Eastern European countries where cases have been reported – this information might be helpful in control measures to prevent entry of the disease from other countries. Via Russia, Ukraine and Belarus, wild boar populations in the European Union territories became infected – and various farms, often small but sometimes large, had to be cleaned. In September 2018 the virus made a big leap, infecting a few wild boars in Belgium. Knowledge of all the outbreaks across the continent (see table below) can help countries to take the right precautions on time.

Outbreaks of ASF in Europe to date (2018)

Management

In the prevention and control of ASF, four crucial steps may be distinguished, of which all are important in order to limit the damage resulting from an outbreak. These steps are researched and well-put by Wageningen Bioveterinary Research in Lelystad, The Netherlands as follows:

1. Prevent introduction

The following emerged to be important on the control of ASF:, “In the Netherlands, any suspected cases of ASF must be reported to the [authority] that, after confirming the diagnosis, [is responsible for controlling] the disease. If pigs have died, but there is no immediate suspicion of ASF, there is an option – as part of an early-warning system – to have a dissection carried out at the Animal Health Service or by a designated and approved veterinary practice. If the findings from the post-mortem dissection resemble ASF, the pathologist will report this suspicion to the Netherlands Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority (NVWA).”

Introduction can only be prevented by exercising extreme care with animals and products from abroad that might carry infection. In this respect, the main measures are:

- A ban on the import of live animals, meat and meat products from regions where African swine fever has been reported. Also safeguard against meat products that might be brought in from affected regions by individuals – for example by truck drivers on long routes, commuting foreign workers, hunters hunting abroad and tourists.

- A ban on swill feeding (as seen in China following the 2018 outbreak). Also be alert to exposing pigs and wild boar to potentially infected food products. Pig farmers must control visitors bringing food onto their farms.

- Cleaning and disinfection of livestock transports returning from abroad.

- Cleaning and disinfection of materials used when hunting in or in the vicinity of infected areas.

2. Limit further spreading

In most cases, the introduction of the virus to a new region will initially go unnoticed. It can be assumed that there will be a few weeks between the time of introduction and the first diagnosis.

During this phase the virus will be able to spread unchecked to other farms. Measures will be needed to limit this as far as possible. Under all circumstances:

- Restrict the number of contacts between pig farms. This applies primarily to contact between animals, but also to indirect contacts, such as interpersonal contact and to contact via manure, trucks and other materials.

- Ensure that essential contact is rendered safer by mandatory hygiene precautions.

- Encourage intelligent hunting: well organised and focused on females – intensive, unrestricted hunting in a 50km radius around infections, so in areas where there are no ASF infections. We need to reduce the wild boar population by 20 to 30 times.

- Establish electric and smell fencing around the infection epicentre, combined with a cull to kill as many boars as possible in the surrounding area.

3. Trace a possible infection early

Efforts to control ASF at source require the ability to rapidly trace any new outbreak. Pig farmers bear great responsibility in this, since they will be the first to observe suspected symptoms. In this regard, it is essential that the right follow-up steps are taken quickly to confirm the presence of ASF in the laboratory or to rule it out.

4. Controlling an outbreak quickly and efficiently

Since treatment of the disease is not possible, if an outbreak occurs, ASF will initially have to be controlled using zoo-sanitary measures:

- culling animals on infected farms, followed by cleaning and disinfection;

- tracing possible contact farms, followed by quarantine or preventative culling;

- tightening biosecurity measures;

- a transport ban on pigs and pork products;

- improving surveillance in the region where the outbreak occurred.

Implications in Europe

The Belgium outbreak of ASF resulted in exports to countries outside and within the European Union being put on hold.

The impact on the welfare of the affected pigs will be large. Apart from that, it will have a large psycho-social impact on pig farmers whose operations have to be cleared out and on others involved.

Outbreaks will have a major economic impact, including export bans, the loss of healthy pigs and transport bans.

There would be little hope of stopping the virus circulating in very dense wild boar populations, such as those found in Poland or Germany. In the case of confirmed outbreaks in these regions, wild boars might need to be killed en masse, which might not go down well with animal-rights and -welfare activists. Germany, for example, is extremely concerned about the spread of ASF to the Czech Republic and the region around Warsaw in Poland; Germany is even considering culling 70 percent of its wild boars by shooting.

It is a big challenge to bring in uniform control measures. For example, in the Netherlands pig farmers are also concerned and through their farming associations are calling for effective and uniform measures across the European Union. In January 2018 questions on ASF were put to the Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality in the Lower House of Parliament.

Controlling the human factor in spreading the disease might also pose a challenge, particularly if there are no benchmark rules from region to region. But this is necessary since research into the spread of ASF in Eastern Europe has indicated that human intervention has played a major role in the outbreaks.

By Matthew Wedzerai

Matthew Wedzerai holds an MSc in Animal Science (Animal nutrition) from Wageningen

University, The Netherlands. He also holds a Diploma in Pig husbandry & Animal Feed,

PTC+ College, The Netherlands.

He has 7 years’ experience in the pig husbandry and animal feed industry. Since 2014 he

has been contributing to the pig and feed industry through his articles based on scientific research. He is also a Copywriter and Editor of the editing company, Spotless Copy, a firm that

provides professional copywriting and editing services.