The eve of disruption: How changes in retail and consumer trends might affect pork consumption - and production

Today, almost any product in the world is at your fingertips - literally. A mouse click or screen tap is all you need for access. And often you can get the item you covet delivered the next day - at no extra cost.By Marlys Miller

Any business that produces, markets or sells a product - including food - now faces unprecedented competition, often from companies that weren’t remotely close to being players a short time ago.

These new and heated rivalries drive the need for product differentiation while fueling more aggressive, innovative and disruptive marketing techniques that tap the power and immediacy of today’s digital media.

In this special report, Pig Health Today looks at disruptions in the consumer and retail landscapes and how they could forever change the US pork industry and the way pigs are raised.

Disruption has seeped into every facet of society. The dominant population group is shifting; political upheaval is rampant; new technologies and trends develop and fizzle at lightning speed; and social media has seemingly reduced the planet to the size of a marble.

Consider how Uber revolutionized taxi service, how Airbnb coaxed many travelers to check out of hotels or how Amazon disrupted all things retail. What began as the demise of local book stores quickly morphed into a complete overhaul of how Americans shop for everything.

Amazon’s Whole Foods acquisition signals that groceries are the new frontier for the online retailer (See related article, “The Amazon Factor”).

To paraphrase a question from a 1960s folk-rock anthem about change, “You don’t believe we’re on the eve of disruption?”

Everything all the time

“Whether it’s cars, clothes or the food they put into their bodies, consumers today can ask for specific attributes - and they can get them,” Justin Ransom, supply chain and consumer insights specialist who has worked with the world’s largest supply chains, including McDonald’s.

“Suppliers that do a good job of listening to the customer and providing what they want are growing their businesses.”

The rise of consumer empowerment can be traced back to the “age of information” and the Internet’s reach. But Ransom cites 2010 and the ubiquitous smartphone expansion as the tipping point.

“Increasingly, people are getting everything from their phone,” he notes. “It has connected people and products like never before.”

He points to post-2010, when the paradigm shifted from sellers/suppliers stating “this is what we’re bringing you” to consumers saying “this is what we want.” Hence, the marketplace has evolved to what Ransom calls the “age of the customer.” Products, purchases and providers will never look the same.

‘Outside industry’s control’

Business experts agree.

“In the last 5 or 6 years, no trend is causing more concern in the food industry than what’s going on with consumers,” says Mary Shelman, president of Shelman Group, who advises companies how to strategically position their businesses for growth, “and it’s completely outside of the industry’s control.” Previously, Shelman studied global food trends for 11 years at Harvard Business School.

Dallas Hockman, vice president of industry relations for the National Pork Producers Council (NPPC), sees it another way.

“These are exciting times. We’re going to see more changes in the pork industry in the next 10 years than we have in history,” he says. “Pork will see more product segregation, but with that comes opportunity for the producer to move up the value chain. A producer can choose whether to produce commodity pork or move to value-added.”

He cites the record-setting hog supply, new packing plants coming online and pork’s increased popularity at home and internationally as signals of a growing industry.

“There are a lot of opportunities when you see this much growth,” Hockman adds. “Change is neither good nor bad, but you’re going to be very uncomfortable if you’re not Ok with change.”

Changing population

Although there are many factors driving consumer demands, the millennials’ influence cannot be overlooked. Just as the baby boomers - those born after World War II through the early 1960s - once dictated workforce trends, politics, television shows, car models and everything in between, so too will the millennials. As of 2016, millennials - people born between the early 1980s and early 2000s - made up the largest US population segment. They now outnumber baby boomers 83 million to 75 million - and will continue to overtake the aging boomers (See related article, “What Makes a Millennial”).

Millennials have since come into their own, having families and entering their peak earning period. A study by businessconsulting powerhouse Accenture reports that millennials now spend $600 billion annually. By 2020, that is projected to grow to $1.4 trillion and account for 30% of total US retail sales.

These consumers also exhibit some behaviors that are markedly different from previous generations. Maintaining health and wellness is part of their daily routine; dieting is not part of their equation. They’re more focused on making what they perceive to be healthy choices. For many, that means paying more to ensure what’s not in the product as well as how it was produced versus whether it’s a good value.

“They want to eat better. They emphasise freshness,” Hockman says. “And they’re willing to pay more for food.”

Food part of identity

Interestingly, while millennials want immediate information and want to know more about food, “they don’t know what to do with that information,” he notes. “And they aren’t consistent; they may go an entirely different route on the weekends.”

Food is a part of millennials’ identity and life experiences, Shelman points out. So, ethnic cuisine often tops their list, which means meat is an ingredient versus the entrée. “They have a new interest in cooking but they don’t know how,” she adds. Their perception of a “home-cooked meal” is different, too (See related article, “Make way for meal kits”).

But although it’s true that millennials are the dominant pack, other consumers tend to follow once they see product options expand. “People across nearly all demographics are paying more attention to food. They care about what they’re eating,” Shelman says. “They want to know where things are grown and how it’s produced - the product’s journey.”

Values shift demand

While it may be tempting, it’s important not to dismiss these trends as a “millennial thing” rooted in self-absorption or affluence, trend watchers say. It’s more about a societal and cultural change.

“Today, consumers have higher expectations for authenticity, ingredient focus, health, sustainability and overall social responsibility,” says Jarrod Sutton, vice president, domestic marketing for the National Pork Board (NPB). “The speed of communication and access to information is fueling these rapidly changing demand drivers.”

But having more information doesn’t translate to having a credible or complete story. The unlimited digital venues also make it easier for individuals to interact with only like-minded people. According to the International Food Information Council’s (IFIC) 2017 Food and Health Survey, involving 1,002 Americans ages 18 to 80, eight in 10 participants said they get conflicting advice about what to eat or avoid, and many doubt their food choices.

Friends and family

“The top trusted sources for food information is a registered dietician or a healthcare professional,” points out Tamika Sims, director of food technology information for IFIC. “But in reality, individuals frequently get information from friends and family. So, they often get conflicting information.”

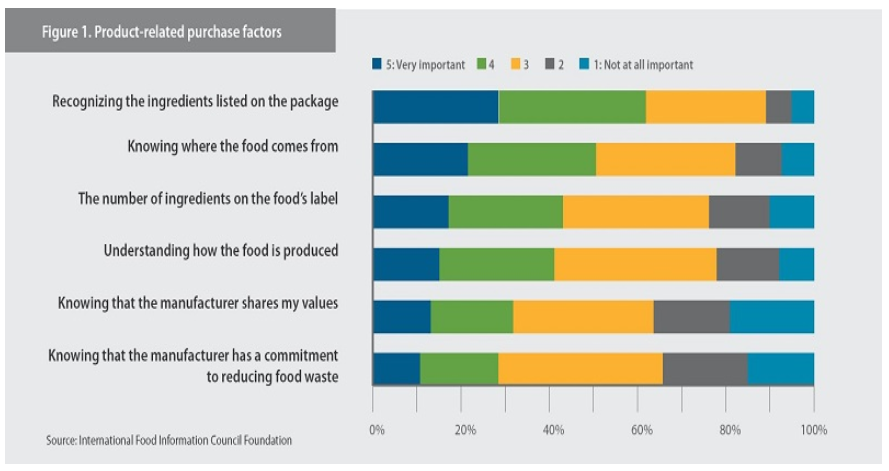

In the 2017 Power of Meat study, conducted for the Food Marketing Institute and the North American Meat Institute, nearly 50% of millennials cited values or “supporting a cause” as a purchasing consideration. However, these sentiments have spilled over to more traditional, mainstream consumers. The IFIC survey found that nearly one-third of all consumers said it’s highly important to know that a company shares their values (Figure 1).

Are your values my values?

When it comes to what Americans eat and why, the production process, food origins and perceived corporate values have a big impact on decisions.

Some values get lumped together, whether accurate or not. For example, most consumers believe “organic” means free of everything but also includes animal welfare. Fact is, there are no animal-welfare guidelines currently tied to organic meat and poultry products. USDA’s Agricultural Marketing Service has proposed a rule for such standards, but it was terminated by the Trump administration as of late December 2017. NPPC and the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association both opposed the rule.

The term “organic” is more regulated than “natural,” which refers to the way meat is processed, and has largely become diluted and irrelevant. However, the “organic” tag - which, for many, conjures up bucolic images of heritage farming practices - carries more weight with consumers. The 2017 Power of Meat study found double-digit growth for organic, antibiotic/hormone-free, grass-fed and other special attributes of meat products (Figure 2).

Consumers prioritise meat attributes

Shoppers are most interested in the animal’s diet/treatment and origin, according to the 2017 Power of Meat study. Surveyed consumers identified several categories where they said they want to see expanded meat and poultry offerings.

Meanwhile, the grocery store’s traditional offerings are growing at a much smaller rate. Among Power of Meat study participants, nearly half said they purchased organic/natural meat/poultry in the past 3 months; 19% planned to purchase more in the year ahead.

‘No BS’ and clean labels

Pork producers know all too well that changes in consumer preferences don’t begin in the retail marketplace. They tend to start at the restaurant and foodservice level. For example, in 2016, Dickey’s Barbecue Pit - the family-owned American barbecue chain based in Dallas - announced its “No BS” (as in no bad stuff) initiative. The company said it would source only chicken humanely raised and raised without antibiotics. Roland Dickey Jr., the company’s CEO, said the initiative would eventually include beef and pork products as the supply chain allows. “I think you’re going to see antibiotic-free and sustainable meats everywhere 5 years from now,” he added.

No question, meat from pigs, cattle and poultry “raised without antibiotics” is a hot foodservice and retail trend. Consumers tend to put antibiotics - those FDAapproved medications used to prevent, control and treat farm-animal diseases - in the same boat as hormones, pesticides and food additives as having the most direct impact on them.

Following a decade of research, the Center for Food Integrity’s (CFI) 2016 study found that more than half of consumers surveyed were concerned about antibiotic resistance due to on-farm usage. An equal amount was concerned about antibiotic residues in meat, milk and eggs.

What consumers want

Among consumers surveyed by the Natural Marketing Institute, 67% said it was important that their grocery store carried hormone-free meat and poultry products (even though hormones are not used in pork or poultry production), and 66% responded the same way for antibiotics.

Sutton points to a Nielsen survey that shows pork “raised without antibiotics” currently accounts for significantly less than 1% of total fresh-pork sales. “That said, it is a growing segment that has the retailers’ attention,” he adds.

In contrast, “no antibiotics ever” (NAE) poultry production accounted for 20% of 2016’s US production - up nearly 67% from 2015 and a seven-fold increase since 2014, estimates Greg Rennier, president of Rennier Associates, Columbia, Missouri, who tracks poultry feed-medication sales and usage trends. NAE broiler feeds topped 40% in 2017.

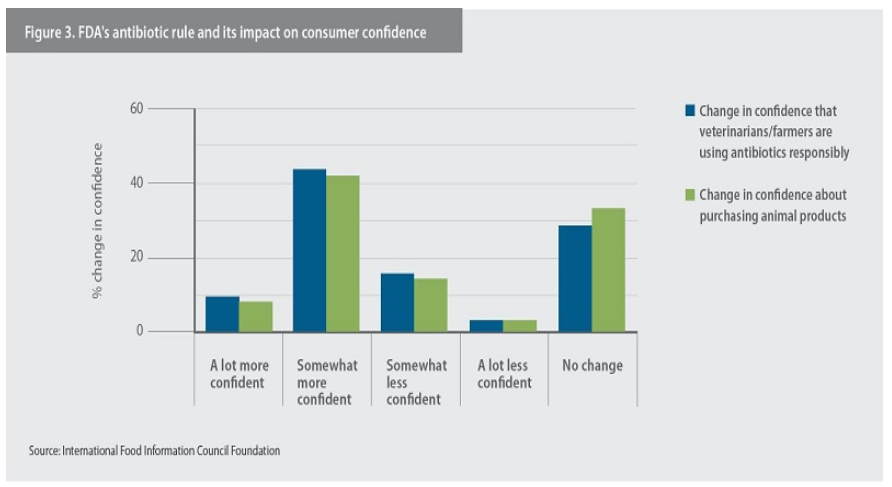

FDA’s antibiotic rule increased confidence

On a positive note, the IFIC study shows that FDA’s new rules on antibiotic use on farms - those restricting the use of antibiotics deemed medically important to humans - has helped balance the public’s understanding (Figure 3).

Nearly half of the participants in IFIC’s 2017 survey said FDA’s new rules for on-farm antibiotic use raised their confidence that such products are used responsibly.

“They also said it made them more confident about purchasing animal products,” says IFIC’s Sims. “This is particularly interesting because government agencies rank pretty low as a food information source for consumers.”

Unfortunately, headlines were cited as the most common source for antibiotic information associated with animals.

Sims points out that although the IFIC survey shows that more than half of consumers were confident in the US food supply, the trend has declined a bit. Also, 43% said they have changed eating habits due to food-safety concerns.

Animal welfare continues to garner consumer attention and, ironically, is not associated with responsible antibiotic use. Rather, the thinking goes: “If animals were raised in more natural conditions, you wouldn’t need antibiotics.”

NPB’s Sutton points out that since 2011, there has been a 45% increase in food-product launches with an animal well-being label claim and a 72% increase in environmentally friendly claims.

What’s ‘sustainable’?

This leads into sustainability - another ill-defined concept that, in the minds of some consumers, wraps many of their values together in a neat, clean package. “The convergence of health and sustainability has led to a clean-label imperative, with absence claims and fewer, healthier ingredients perceived to be sustainably grown,” Sutton says.

Research by the Kerry Group, an international food-ingredient company based in Ireland, reports more than half of consumers polled said they were familiar with “clean labels,” but just 38% indicated a strong understanding of what it actually means. Instead, respondents had a range of interpretations, most applying their own vague qualifiers such as “farm grown,” “sustainably produced” or “made with real ingredients.” Notably, nine in 10 said they look for clean labels and will pay more for such foods.

Americans perceive a clean label as one with a small number of simple, easy-to understand ingredients. “Ingredients that read or sound like chemicals are going to be a big challenge,” according to Renetta Cooper, Kerry Group’s business development director. “Clean label is a big trend and moving very quickly.”

Notably, last August, Hy-Vee - a chain of 240 grocery stores in the Midwest - announced plans to eliminate more than 200 artificial ingredients or synthetic chemicals across 1,000 Hy-Vee-label products by July of 2018. According to the company’s news release, the move is part of Hy-Vee’s Clean Honest Ingredients initiative.

Transparency equals trust

“Transparency is becoming table stakes with food retailers,” NPB’s Sutton adds. “But consumer expectations for transparency do not translate into demand for perfection - rather, honest intent with action.”

This is a conversation about trust, he adds. “Trust in farming and farmers, trust in veterinarians and trust in the food system.”

Sutton also believes pork producers and veterinarians have an opportunity to embrace, define and communicate their practices and shared values with consumers.

To underscore this, CFI’s long-running research shows that communicating shared values is three to five times more important to earning consumer trust than sharing facts or even demonstrating expertise.

“Building trust begins by demonstrating ways in which your values align with those of consumers,” says J. J. Jones, co-founder of Roots & Legacies Consulting, Manhattan, kansas, and a CFI consultant. “Consumers want to know that the folks growing and producing food care about issues like the health and safety of food, high standards in food-animal care and environmental stewardship.”

CFI’s research also shows that consumers are responsive to what farmers have to say. In its 2016 study, farmers ranked seventh out of 15 “most trusted sources” on food-related issues. In order, the family doctor, family members, university scientists, dietitians, friends and nutrition advocacy groups scored higher. But consumers were curious about agriculture, with 80% expressing a strong desire to learn about how food is produced. Nearly 70% had a positive view of agriculture.

“Transparency is about illustrating your principles - what you stand for - caring for pigs, people and the planet. Best practices - the actions you take on your farm. Proof that you’re doing what you say; that means things like audits and opening your doors, if not literally then online,” NPPC’s Hockman says.

‘Great sustainability story’

Whether it’s online or in person, pork-industry personnel, from producers to workers to veterinarians, need to be prepared for critical day-to-day conversations - anytime, anywhere, says Brad Greenway, a pork producer in Mitchell, South Dakota, and 2017 America’s Pig Farmer of the Year.

“People want information and there are so many places to get it today. But if they want to know about activities on a pig farm, antibiotics or sustainability, we need to be the people they listen to,” Greenway says. “We have a great sustainability story to tell. By raising pigs indoors, we use less feed and land, have a smaller carbon footprint and distribute nutrients back to the land more effectively.”

Unfortunately, that message isn’t getting out. CFI’s 2016 survey shows that more than half of respondents aren’t convinced that farmers are taking good care of the environment.

Greenway emphasizes that communicating with consumers doesn’t have to take a lot of time or effort. “Post a picture or video, have a conversation, invite a group to the farm, and don’t forget your neighbors,” he adds. “But humanize the message. Show them who you are, why you do what you do, and that we think about what’s right for the animal every day.”

Companies and brands are engaging with consumers more directly. For example, New Jersey’s Applegate Farms - an organic meat producer and marketer acquired by Hormel in 2015 - uses UPC codes to link consumers to a web page that shows its farmers, where the pork comes from and how it’s produced.

But in all of this, it’s equally important to recognize it’s not about educating consumers. It’s about listening - really listening - understanding consumers’ concerns and finding common values. “Engage, don’t educate,” Jones says.

Put simply, if you’re not willing to listen to me, then why should I listen to you? “Farmers also should be listening to learn,” Shelman says. “If you start by thinking you’ll educate someone, you’ve already lost.”

Effect on production

So, what is the long-term impact of the disruptions that food - and pork - are facing today? And how might it affect production on the farm?

“We’ll continue to see product differentiation and fractured demand,” Shelman points out. “Last year, specialty products, natural products, in supermarkets grew at 10%. Conventional products grew at 0.1%.”

As companies look for ways to differentiate their product, issues like animal welfare may find a place at the table. For example, Business Benchmark on Farm Animal Welfare, which has tracked and measured company practices on animal welfare since 2012, reports that more food companies are describing farm-animal welfare in terms of opportunities - financial and reputational - and are positioning the issue as part of their corporate responsibility versus simply a compliance requirement.

Another example: In 2017, Smithfield Foods announced a new line of fresh-pork products from pigs raised without antibiotics, marketed under its Pure Farms brand. According to the company, products within the Pure Farms brand also “meet the highest level of USDA standards with minimal processing and no steroids, hormones or artificial ingredients.” The products, which include fresh-pork cuts, ham, breakfast sausage and bacon, are available at the retail and foodservice levels. NPPC’s Hockman expects differentiation will continue throughout the marketplace, including among pork production.

‘Won’t be a uniform market’

“We’ll see more alignment between producers and packers, and companies will more directly prescribe production methods. To what supply level will depend on the marketplace and consumers’ willingness to pay for it,” he says. “But it won’t be a uniform market or encompass the whole meat case. If one player goes one direction, another will feature something else.”

Expect the meat category to explode with acquisitions and new brands. For example, Tyson buying Hillshire Farms and aligning specific attributes to its Naturals line such as “farm values,” “no artificial ingredients,” “simple and delicious.”

Aligning with values

Notably, with each brand comes the die-hard commitment to brand protection. “You only have to look at Chipotle to see how far a brand can fall,” Hockman says. “So, producers can expect to see more auditing and certification programs to confirm on-farm practices.”

The top issues and on-farm practices that will continue to nag pork producers include how food is produced and processed, treatment of animals, environmental sustainability, antibiotic use and growth hormones, he notes. Breed differentiation - heritage breeds, Duroc pork, meat-type and quality genetics, and artisanal products - also will find expanding markets.

The bottom line: Product or brand expectations among all consumers are higher, and shoppers want to feel good about their choices. Transforming messaging to align with changing social/cultural values is part of building that relationship. Sutton points out that part of NPB’s future strategy is to emphasize the three pillars of pork’s identity - quality, trust and value.

More broadly, supply-chain consultant Ransom advises, “The key is having the right insights into what consumers think they want, and then finding the most sustainable way to move the business to meet those needs.”

He admits that likely includes changes. “Producers need to be prepared to engage with consumers on the positive things they do every day,” he says. “But if consumers are beating you up over something they dislike, then maybe you need to look at the practice. You have to figure out how to bridge that disconnect on their perceptions of how their food is raised.”

Still, Hockman contends that the US pork industry, producers and veterinarians are in a solid position. “This is a brand-new world. But our sector is growing, and pork producers and veterinarians are engaged in industry programs like never before,” he says. “It’s a moving target, but we’re prepared.”