Norwegian legislative debate opens doors for gene editing in the pork industry

In a move that could have huge implications for global pork production, a new way to classify and regulate GMOs has been proposed by the Norwegian Biotechnology Advisory Board this week.The board proposed a renewed public debate and dialogue over genetically modified organisms (GMOs) and 17 of the 20 members voted in favour of a new three-tiered classification for genetic engineering. If adopted, this could offer hope that a number of current pig genetics projects – in particular those using gene editing to reduce body fat and increase disease resistance – could gain fairly rapid regulatory approval.

As the board reflects in a statement: “Genome editing, CRISPR being the prime example, is now being employed by researchers all over the world at an unprecedented pace. The technique allows for targeted genetic alterations such as deleting, substituting or adding DNA, or switching genes on or off without making any changes to the genetic sequence.”

The key to the debate is how far and how fast these technologies have developed – factors that make current legislation appear particularly dated.

The statement continues: “We have to discuss how GMOs are regulated. Current GMO regulatory frameworks, both in Norway, the EU and elsewhere, were developed when genetic engineering was still in its infancy. At the time, the divide between gene technology and conventional breeding techniques was clear. Today, with new technologies giving a much larger range of possibilities, these lines are becoming increasingly blurred. For example, gene editing can be used to make genetic changes that are equivalent to those that can or do arise naturally, or can be obtained using conventional breeding techniques.”

Gene editing can be used to make genetic changes that are equivalent to those that can or do arise naturally, or can be obtained using conventional breeding techniques. Current projects that have gained momentum this year include the Roslin Institute’s work on PRRS-resistant genes, and China’s research on producing healthy pigs with significantly lower body fat.

A three-tiered system

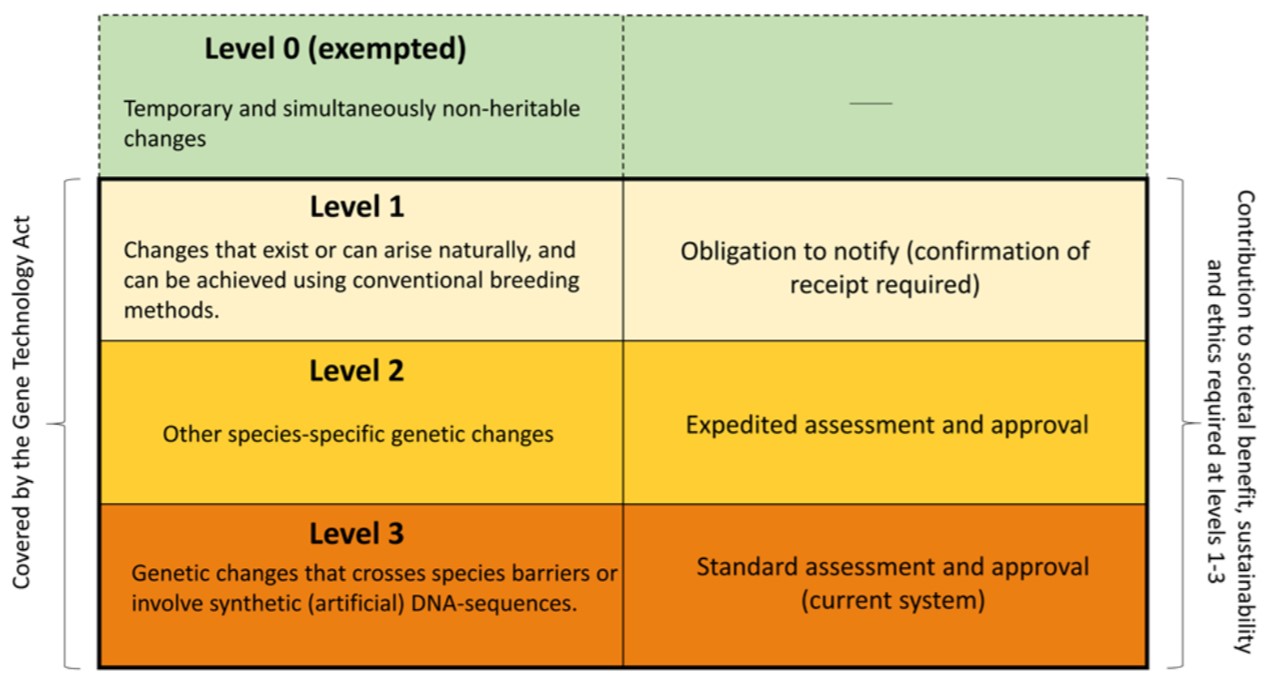

Seventeen members of the board argued that organisms can be divided into different levels, based on the genetic change that has been made, according to general principles. For example, relevant criteria can be whether or not the change is permanent and heritable, whether or not the change can also be made using conventional breeding techniques, and whether or not the change crosses species boundaries.

At the lowest level (see diagram below), a notification to the authorities (receipt required before the organism can be released) may be sufficient. At higher levels, organisms would require approval before release is authorised, but may be subject to different risk assessment and approval requirements.

© Bioteknologiradet

The response has been greeted with enthusiasm by a number of eminent scientists and researchers, particularly those involved in GM-related projects.

As Professor Johnathan Napier, who has led a project developing a strain of GM camelina that produces the key long chain omega-3 fatty acids EPA and DHA, reflects: “It strikes me as a very positive thing - given the interlinked global challenges of climate change, population growth and food security, we need every tool in the box to help address these problems. Genetic engineering and genome editing are technologies which can contribute to solving these global challenges, and it is very positive that Norway is seeking to reconsider how these are regulated.”

Next steps

To facilitate a national debate the board plans to hold open meetings and talks in all of the biggest Norwegian cities over the next months. The deadline for responses to the public consultation is 5 May 2018. More information will follow at www.bioteknologiradet.no/genteknologiloven.