Lessons learned from PRRS outbreak investigations

It’s been three decades since veterinarians and researchers first recognized porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS).[1] Despite years of research and experience, the disease still causes productivity losses in the US worth $664 million annually.[2]By Derald Holtkamp, MS, DVM

Iowa State University, College of Veterinary MedicineAmes, Iowa

Arguably, the industry’s biggest problem is preventing new PRRS outbreaks in sow herds. Outbreaks are reported in about 20% to 40% of sow herds annually. [3] Every time a sow herd has a new outbreak, groups of infected, weaned pigs are transported to other locations, perpetuating spread of the virus.

Why do we continue to have so many new outbreaks in sow herds every year?

The PRRS virus changes over time, and immunity in a sow herd to one isolate frequently doesn’t provide enough protection to prevent a clinical outbreak when a different isolate of the virus is introduced into a herd.

In addition, the virus can be transmitted from one herd to another in multiple ways. Even though research tells us how PRRS virus can be transmitted, it doesn’t tell us the most common ways the virus is transmitted in the field. Only systematic observation can help us answer that question, and without an answer, we don’t know where to focus our bio-exclusion efforts. Still, we have to decide what to do first.

Outbreak investigations help

Toward this end, we initiated outbreak investigations in sow herds in 2013 through a pilot program funded by the Iowa Pork Producers Association. [4] The objective was to identify, when possible, the likely cause of outbreaks, identify gaps in biosecurity and reduce the frequency of outbreaks in sow herds over time.

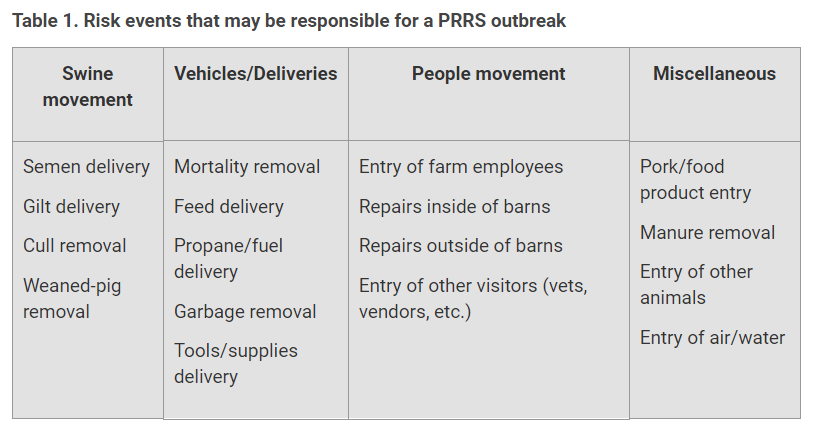

Producers and veterinarians are especially motivated to identify gaps in bio-exclusion and make changes when the pain of an outbreak is still fresh. We conduct the investigations by assessing the risk events where carrying agents enter the site. Carrying agents are defined as anything that can carry the virus into a herd because it’s either infected or contaminated. For example, semen is a potential carrying agent, but it’s not just semen. It’s the semen packaging as well as the delivery vehicle and driver.

The complete list of risk events we assess during an outbreak investigation for a sow farm is shown in Table 1. For each risk event that may be responsible for an outbreak, we assign a rating of high, medium or low.

Employee entry is high risk

The entry of employees and removal of culls were the risk events most frequently rated as being “high.” Of 17 investigations conducted since 2014, each was rated high eight times.

On every one of the 17 farms investigated, employee entry was the most frequent risk event, and the presence of a shower alone wasn’t sufficient to reduce this risk. For several farms investigated, the employees were at risk for PRRSV contamination because they were performing other jobs besides working on the sow farms. These jobs included managing a finishing site, performing maintenance on other swine farms, driving feed trucks, transporting pigs to and from other farms, managing a feed mill and loading market hogs.

In one case, an employee also managed a finishing barn with pigs infected with an isolate of the virus that was over 99% similar to the one that caused the outbreak at the sow farm. The evidence, in this case, was strong enough that we considered it a smoking gun.

On another sow farm we investigated, the shower was located in a detached shed next to barns with no walk-through separating clean and dirty areas. Other observations included the absence of a bench entry where employees could place their socked feet in a cleaner area after removing their shoes. There were also frequent reports of towels on the dirty side of the shower. Employees would enter and exit the barns multiple times daily to leave for lunch, to smoke, to work outside the barns or work at other swine or swine-related premises. In some cases, they were not required to shower in again.

Removal of culls — the other big risk

Producers sometimes viewed removal of culls as a low-risk event because the culls were leaving the farm. However, in several cases, there was a high risk posed by contamination of livestock trailers, swine panels, other equipment and the driver.

For several of the farms investigated, hauling of culls was contracted out to a third party that also transported pigs for other producers, and the identity of those other producers was unknown. This was the case for replacement gilts as well.

In almost every case, the producer relied on the contractor to establish protocols for cleaning and decontaminating trailers, and there was no oversight or auditing. Under these circumstances, the producers had no knowledge of where the trailer and driver had been, what types of swine it had hauled or how well it had been cleaned and decontaminated prior to arriving at the farm to remove culls.

In one case, there was a farm cart dedicated to hauling culls to the road where a bumper-to-bumper transfer was made. This would have reduced risk — except that same cart was used to haul gilts from an on-site gilt-development unit to the gestation barn right after the culls were removed. If the cart became contaminated during the transfer, there was a high likelihood that gilts were infected on the ride to the gestation barn.

Conclusion

Mistakes are opportunities to learn and improve, but making mistakes doesn’t guarantee we’ll learn from them. If we don’t learn, we’re destined to keep repeating the same mistakes.

Outbreak investigations are a great way to identify mistakes and learn from them. It takes time, but the alternative is another three decades of PRRS.

[1]. Keffaber KK. Reproductive failure of unknown etiology. Am. Assoc. Swine. Pract. Newsl. 1989;1:l-9.

[2]. Holtkamp DJ, et al. Assessment of the economic impact of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus on United States pork producers. J Swine Health Prod. 2013;21(2):72-84.

[3]. Swine Disease Eradication Center. Swine Health Monitoring Project. University of Minnesota. Available: https://www.vetmed.umn.edu/centers-programs/swine-program/research. Accessed 6/25/2017.

[4]. Canon A, et al. PRRS, SVA, and emerging and transboundary diseases – systematically investigating swine disease outbreaks with the Outbreak Investigation Program. In: Proc. 2015 ISU James D. McKean Swine Disease Conference. Ames, Iowa. November. 94-97.