PRRS Gate-Keeper Found Using Gene-edited Pigs

ANALYSIS - At the North American PRRS conference in Chicago in early December, Dr. Randy Prather, animal science professor at University of Missouri, shared the process and data behind the incredible discovery – identifying the CD163 gene that is resistant to Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome (PRRS).PRRS is an obvious disease to target as it costs the industry about $664,000,000 per year in North America, and in Europe it's estimated at about $1.5 billion Euros.

“You add all of that up and that's $6 million per day in North America and Europe - that what PRRS is costing,” Dr. Prather said. “We think of this as an economic problem and yes it is, but this is also an animal welfare issue.”

The Case for CD163

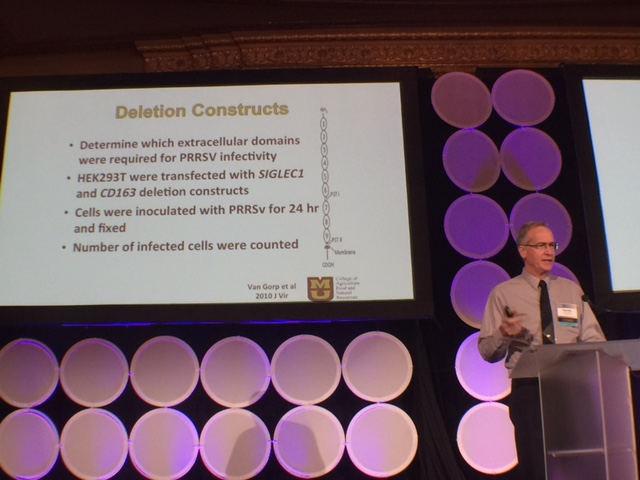

Several studies have been conducted to determine which of these extracellular domains of CD163 are involved in PRRSv infectivity and they have been numbered from one through nine, with a PST I domain and a PST II domain.

“They took some HEK293T cells and then transfected them first with cyclohexane because we know cyclohexane is important for infectivity, right? Well, maybe not?” he said.

They then inoculated cells with PRRS and waited 24 hours and fixed them. Next, they counted the number of infected cells.

CD163 is a member of a gene family, and there's also a human equivalent. Another molecule called hCD163-like exists and has 12 extracellular domains but it does not function in infectivity.

The plan was to swap domains from hCD163-like and CD163 and determine infectivity. The result provided evidence that perhaps one domain's was responsible for the infection process.

This was pursued in two proposed targeting approaches. One was to use a traditional knockout by homologous recombination and additional swap of a stop codon to knock it out.

“We also wanted to pursue the idea of a domain swap because we thought maybe this thing was necessary for life and we really needed to be careful,” he said.

Haptoglobin’s ability to promote binding of hemoglobin to CD163 in humans has high affinity, but not in mice. In mice CD163 accounts for a small part of the hemoglobin clearance. Knockout of CD163 resulted in “no apparent phenotype change… and offspring were viable and fertile.”

A technology called CRISPRS-mediated gene editing was used to genetically edit cells in a few different ways.

The timeline for creating the CD163 knockout pigs for the somatic cell nuclear transfer was about 5.5 to 6 months and most of that was gestation. Genetic engineering somatic cells can take quite a while, he said, but somatic cell nuclear transfer and zygote injection take about a week. Gestation was three months, three weeks and three days. Puberty was six to nine months.

The PRRS Challenge & Results

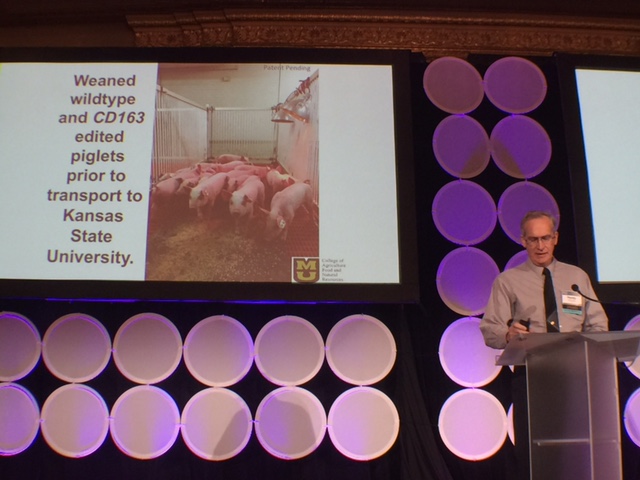

The pigs were sent over to project collaborator Raymond “Bob” Rowland, professor in the College of Veterinary Medicine at Kansas State University. The knockout pig's identity was blinded to the researchers. The pigs were acclimated and then challenged with the virus.

The pigs were sent over to project collaborator Raymond “Bob” Rowland, professor in the College of Veterinary Medicine at Kansas State University. The knockout pig's identity was blinded to the researchers. The pigs were acclimated and then challenged with the virus.

“These pigs were maintained in the same pen so even if it didn't get infected - he's going to cough on everybody else. They were monitored daily for clinical signs, blood was collected and they were terminated at thirty-five, did lung lavage and isolated the lungs and tissues for pathology,” said Dr. Prather.

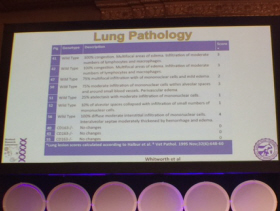

Clinical signs were scored along with respiratory response.

“Over half the pigs by day seven - respiratory signs had diminished; same thing with fever - comes up and it goes down. However, with those three wild type pigs, there's nothing there,” he said. “These pigs don't get a fever; they don't cough. They're in the same pen with these other pigs coughing. There's absolutely no signs.”

For the three knockout pigs, lung pathology was perfectly normal.

Overall conclusions indicated that cyclohexane (SIGLEC1) pigs are not resistant to PRRS. CD163 knockout pigs are resistant to PRRS.

“We knocked out CD163, it's definitely involved in PRRS infectivity. CD163 is a gate keeper,” Dr. Prather said.

What’s Next for CD163?

“This technology is going to allow us to answer a lot of really neat questions about both basic and applied questions for bio medicine but also domestic animal biology and answer some really important questions for agriculture. The debates been on which molecule's involved, I think we now know CD163 is,” he said.