AHVLA Report: Piglet Diarrhoea, Colitis, Oedema Disease, Actinobacillus

UK - The Animal Health Veterinary Laboratories Agency (AHVLA) has reported piglet diarrhoea, colitis, erysipelas, oedema disease and an unusual presentation of Actinobacillus suis, in its Pig Disease Surveillance Monthly Report for November 2014.Enteric Diseases

Sudden deaths and diarrhoea due to clostridial enterotoxaemia outbreaks at different ages

Clostridial enterotoxaemia was diagnosed as one of the causes of yellow watery diarrhoea affecting one to two-day-old piglets in five to six litters in the farrowing batch on an indoor unit. Bright and alert live piglets with mild creamy yellow diarrhoea were submitted for investigation. There were no mucosal lesions and, in one piglet, alpha toxin was detected which, together with supportive histopathological lesions, was consistent with a diagnosis of Clostridium perfringens type A. In the second piglet, histopathology was more suggestive of an enteric virus; although neither rotavirus nor porcine epidemic diarrhoea virus (PEDv) were detected.

In another incident, three dead piglets were submitted to investigate sudden deaths at three weeks of age on an outdoor breeding unit. In the batch of 1,500 piglets, 100 were reported dead with one or two piglets dying within affected litters. The pigs were dehydrated and one had marked purpling of the small intestine with whitening over the Peyer’s patches as shown in Figure 1 (likely diffuse mucosal necrosis) and small intestinal contents were red-brown. A second piglet had marked liquid diarrhoea without specific mucosal lesions.

Clostridial toxins were detected in both piglets, both alpha and beta were present in the diarrhoeic piglet pointing to Clostridium perfringens type C. Alpha toxin only was detected in the piglet which had lesions most consistent with necrotic enteritis (classically type C), however beta toxin is labile and is sometimes not detected. Where necrotic enteritis due to clostridial enterotoxaemia occurs at this later age rather than neonatally, the presence of other enteropathogens, in particular Isospora suis, is worth investigating as a predisposing factor. No coccidia were detected but the ideal submission for diagnosis of pre-weaning coccidiosis is live affected piglets to allow prompt fixation of intestines within minutes of death allowing worthwhile histopathology.

Rotaviral enteritis in neonatal piglets in mainly gilt litters

Live affected piglets were submitted from an outdoor unit to investigate diarrhoea mainly occurring in gilt litters and starting when piglets were one to two-days-old. The piglets had good milk clots in the stomach but gammaglobulin concentrations in two of the piglets suggested low to negligible colostral antibody transfer, and rotavirus was detected in small intestinal contents.

Being from gilt litters where immunity to resident pathogens may not have fully established, and the poor colostral antibody transfer in some of the pigs, are both factors which may have predisposed to disease.

Piglets aged eight to ten days were submitted to Starcross with a history of diarrhoea and mortality in the first ten days of life. The problem occurred initially in gilt litters then spread to some older parity sow litters. There was poor response to various antimicrobial treatments. The piglets were depressed with mustard-coloured diarrhoea evident. Laboratory testing confirmed the presence of rotavirus in one piglet and villous atrophy supportive of a viral cause was seen histologically in two piglets and no PEDv was detected. In this case, gammaglobulin estimation showed adequate colostral antibody transfer.

Rotaviral enteritis was also the likely cause of periodic bouts of diarrhoea in three-day-old piglets on an indoor unit with just 3-4 litters affected in each farrowing batch. Rotavirus was detected in a diarrhoeic sample which was submitted.

Coccidiosis contributes to mortality, diarrhoea and poor growth in piglets

Coccidiosis due to Isospora suis infection was confirmed contributing to piglet mortality of 25-30 per cent in 24 litters in two farrowing houses. The history was of diarrhoea, vomiting and death between two and tendays-old. Recovering piglets were reported to then grow poorly. Two batches of three live pigs ranging in age from three to ten days were submitted to Sutton Bonington for post-mortem examination. In all the piglets, small intestine contents were yellow and watery with white flecks. The small intestinal mucosa was slightly thickened and velvety and the large intestinal contents were yellow and watery to pasty.

The Isospora suis oocyst count per gram was 129,500 in a pooled intestinal content sample and a diagnosis was confirmed by histopathology. The relatively high mortality and early age of onset suggests earlier involvement of another enteropathogen, such as clostridial enterotoxaemia or rotavirus prior to the coccidiosis, although no other enteropathogens, including PEDv were detected.

Colitis due to Brachyspira pilosicoli

Three incidents of colitis due to Brachyspira pilosicoli were diagnosed. In one, diarrhoea was described affecting 20 per cent of the group of housed 16-week-old finishers. In the second, it was the cause of loose faeces in housed 15-week-old finishers. In this case less than five per cent were affected and there was no associated mortality. In the third, no morbidity figures were available but disease was affecting nine-week-old pigs in a straw-based system.

Brachyspira intermedia was the only organism detected in two faecal samples submitted from 21-weekold housed finishers of which 10 to 15 per cent had diarrhoea. The significance of this was difficult to assess without histopathology to follow-up. No Salmonella, porcine epidemic diarrhoea virus or other Brachyspira species were detected.

Colitis due to a combination of Brachyspira pilosicoli and salmonellosis

Diarrhoea and poor growth were reported in a batch of 1,000 seven-week-old pigs that were sourced from breeding farms from another region of GB. The pigs had an interim stop for three weeks on a farm before they arrived in the Thirsk region. There was evidence of diarrhoea prior to the arrival on the finishing farm and this partially responded to colistin treatment in the water on arrival. However, some diarrhoea persisted and some pigs were showing significant ill thrift.

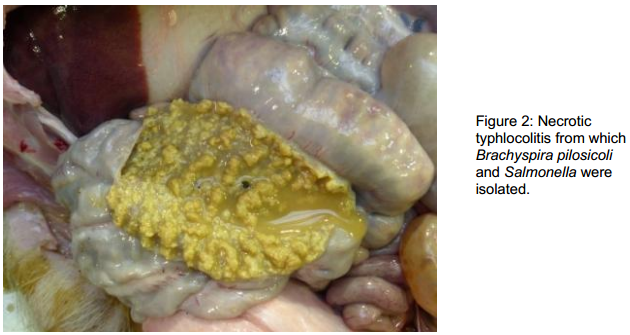

The pigs had been vaccinated for PCV2 and Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae at weaning. One affected pig was euthanased and submitted to Thirsk for investigation. Post-mortem examination revealed a diptheritic typhlocolitis; the walls and mucosae of the caecum and colon were irregularly thickened with the mucosa covered with a yellow-white layer of necrotic material, as illustrated in Figure 2. Faeces were markedly liquid with no evidence of blood or mucus. Brachyspira pilosicoli and a monophasic Salmonella typed as 4,5,12:i:, phage type 193 were both isolated and, although the gross appearance of the large intestine was mainly suggestive of salmonellosis, histopathology, that included special stains for spirochetes, confirmed that the Brachyspira pilosicoli was also contributing to the pathology in this instance.

Abdominal catastrophes in adult breeding pigs dying on two units

In the first incident, two adult pigs were submitted to Sutton Bonington from a 1,000-head breeding unit. One was a boar found dead in his pen, the other was a sow seen to be off-colour which then died suddenly when being fed. Both had distended abdomens and in the boar there was a diffuse, fibrinous peritonitis. A 360-degree torsion of the mesentery associated with the distal small intestine was identified. In the sow there was also a diffuse, fibrinous peritonitis, but intermingled within this were large amounts of ingesta. The stomach was distended and heavy, with 12kg of washed stones recovered from the lumen. A perforation of the jejunum was identified as the origin of the peritonitis.

The second incident was diagnosed in an outdoor breeding herd in which six parity 2 and 3 sows were found dead over a period of a month and two found dead one morning were submitted to Bury St Edmunds for investigation.

Fatal mesenteric torsions were present in both and large quantities of stones were noted in both stomachs and large intestines. In one of the pigs, these weighed 8kg at each site. This is likely to have resulted in instability of the large intestine and predisposed to torsion. Ingestion of excessive quantities of stones is more frequently seen in young replacement breeding pigs, new to living outdoors. When it occurs, it merits a review of the frequency and method of feeding.

Respiratory disease

Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome diagnosed on a continuous unit

An increase in mortality to five per cent, respiratory disease and pasty-grey diarrhoea in the two- to three- weeks after weaning prompted submission of three dead pigs to Bury St Edmunds from a continuous outdoor unit. PRRS-associated pneumonias were confirmed in two by immunohistochemistry and PCR – the pigs had been vaccinated for PRRS, the immunohistochemical detection of PRRSv in the lungs indicates that in spite of vaccination, the virus was implicated in the respiratory disease.

Streptococcus suis types 2 and 8 were isolated from the lungs as likely secondary infections and one of the pigs also had salmonellosis due to S. Typhimurium Copenhagen phage type 193. The continuous nature of the unit was likely to be facilitating persistence of PRRS on the unit with susceptible pigs being introduced at regular intervals.

Bacterial pneumonias in lungs from the abattoir

Significant numbers of lungs being affected with pneumonia at slaughter prompted the submission of 10 plucks from the abattoir. Four of the ten plucks were affected with cranio-ventral consolidation with lung scores up to 21 (of a maximum of 55) in those which had no lung lobes missing and could be scored.

Pasteurella multocida was isolated from three of the four lungs, together with Streptococcus suis type 2 from one, and porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSv) was detected by PCR in one of the lungs. Histopathology was consistent with a bacterial pneumonia; however submission of lungs from the abattoir is not ideal for complete diagnosis as the disease is likely to be chronic by this stage and testing may miss earlier involvement of other pathogens, particularly viruses.

Typical Glasser’s disease outbreaks causing respiratory disease, nervous signs and lameness

Respiratory disease, lameness and 1 per cent mortality over a two-day period were reported in 10 to 11-week-old pigs. Two dead pigs were submitted and both had severe fibrino-purulent polyserositis lesions from which Haemophilus parasuis was isolated confirming Glässer’s disease. No viral involvement was detected.

Another outbreak of Glässer’s disease was diagnosed at Bury St Edmunds, on this occasion causing nervous signs. Three dead pigs were submitted to investigate the cause of nervous signs (recumbency, paddling, opisthotonus, nystagmus) and sudden deaths affecting 20 of 750 eight-week-old pigs, of which 15 pigs had died. One pig had a severe fibrinous pleurisy, another had severe fibrinous polyserositis and the third had non-specific lesions.

The findings were suspicious of Glässer’s disease and this was confirmed by isolation of Haemophilus parasuis from visceral sites of the pigs with fibrinous serositis, and also from the meninges of the pig with non-specific lesions. No underlying viral infection was detected. Isolation of H. parasuis can be difficult and successful culture, as in these cases, is helped by submission of a batch of untreated freshly dead pigs.

Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae with pasteurellosis outbreak in finishers

A 21-week-old fattening pig was presented to Shrewsbury for postmortem examination following the death of five pigs from a group of 580 within two days. The pig had shown malaise and was euthanased prior to submission. There was consolidation of the cranial right lung and the remainder of the right lung and accessory lung lobe were dark and firm on palpation. There was also a fibrinous pleurisy with adhesions from lungs to the inner thorax. Pasteurella multocida and Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae were both isolated from the pneumonic lung and no viral involvement was detected.

Systemic disease

Erysipelas outbreaks in unvaccinated pigs

Erysipelas was diagnosed at Bury St Edmunds as the cause of five deaths from a group of 600 13-week-old indoor rearing pigs in which another 15 were affected with lameness and respiratory signs. The pluck submitted from a dead pig showed evidence of pulmonary oedema which was due to heart failure caused by severe valvular vegetative endocarditis. Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae was isolated from the valve lesions confirming the diagnosis.

E. rhusiopathiae was also isolated from heart valves with lesions of vegetative endocarditis submitted to Shrewsbury from two, five-month-old pigs, to investigate the cause of malaise and sudden deaths. Sixteen pigs were unwell in a group of 400 and 13 had died on a farm with 1900 pigs. The continuous nature of the unit and strawed system without regular cleaning and disinfection may have allowed accumulation of high levels of contamination with E. rhusiopathiae. Once clinical cases occur, this adds to the infection challenge to pen-mates and an outbreak can ensue. Improving hygiene and pig flow is an important part of control and occasionally vaccination of growing pigs is merited where successive batches of pigs are affected.

Nervous disease

First APHA diagnosis of oedema disease in East Anglia for many years

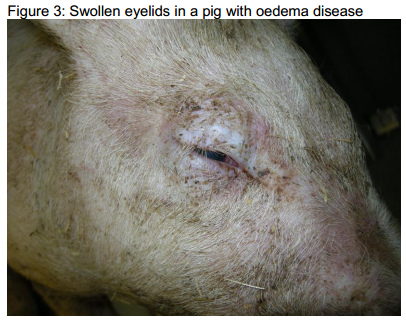

Oedema disease was diagnosed as the cause of malaise, nervous signs, swollen eyes and death of 30 pigs from a group of 600 eight-week-old indoor growers over a period of a week. Three dead pigs were submitted, two had swollen eyelids as shown in Figure 3 and there were other non-specific lesions including reddening of the skin of the ventral abdomen, fibrin stranding and excess fluid in the pleural cavities and prominent meningeal blood vessels.

The clinical signs had raised the suspicion of oedema disease and this was confirmed by isolation of haemolytic Escherichia coli strain E4 (serotype O139:K82) from the small intestine, a strain known to be associated with oedema disease. Brain histopathology revealed multifocal asymmetric acute necrotising panencephalopathy and other histological features characteristic of oedema disease and reflecting the effect of the shiga-like toxin elaborated by the E. coli. This is the first diagnosis of oedema disease in the East Anglian region for many years; interestingly, increased diagnoses of oedema disease elsewhere in the country have been noted in 2014 although the reasons for this are unclear. Oedema disease tends to affect rapidly growing pigs and feed factors including changes in diet or nutrient quality may be involved.

Musculoskeletal Disease

Unusual presentation of Actinobacillus suis causing spinal abscesses

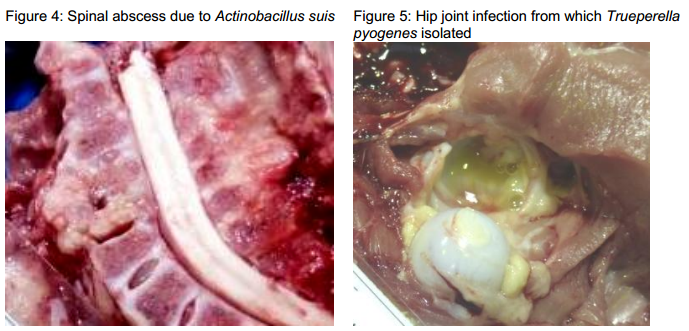

A breeder-finisher unit reported sudden onset lameness in pigs from one- to seven-weeks-old with a poor response to antimicrobial treatment. Between five to 10 per cent of each batch of pigs was affected with pigs becoming unwilling to stand or move. Three such cases aged from one to four-weeks-old were submitted to Thirsk for investigation, one of which was showing hindlimb paresis and another with obviously swollen hind-limb joints. There was no evidence of infection at the sites of tail docking or teeth clipping, nor at the navels. One pig was found to have a spinal abscess affecting cervical vertebrae 7, (Figure 4) another to have a spinal abscess at thoracic vertebrae 2 and 3 and the third had a suppurative polyarthritis (Figure 5), multiple abscessation in the lungs and a fibrinopurulent pleuritis.

Actinobacillus suis was isolated from the spinal abscesses which were in two one-week-old pigs while Trueperella pyogenes was isolated from the joints and lung of a four-week-old pig and probably represents secondary infection. A. suis colonises the respiratory tract of pigs and is most commonly encountered causing septicaemia in young piglets. It can also be involved in respiratory disease and septicaemia in older pigs, and in localised infections following thromboembolic spread, as is likely to have occurred in this outbreak.

Polyarthritis due to erysipelas causing poor growth

Three 20-week-old pigs were submitted to Bury St Edmunds to investigate a problem of poor growth in pigs derived from a group of gilt litters born at a similar time. The gilt fertility had been poor and stillbirths were delivered but not submitted for investigation. Most of the 75 pigs weaned from these litters had grown much more slowly compared to others on the small outdoor breeder-finisher although the pigs did not die. There was concern that the pigs may have become persistently infected with Border disease virus through in-utero infection as there were also sheep on the farm. The pigs were found to be small for their age but not wasted and they all had severe suppurative polyarthritis with thickened joint capsules suggesting the lesions were chronic. Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae was isolated from the joints confirming erysipelas as the cause and no Border disease virus was detected by PCR.