How is PED Virus Impacting Hog Markets?

US - Just what can we say about the impact of porcine epidemic diarrhoea (PED) virus on summer pig numbers and, by extension, winter hog slaughter? That question is floating through markets these days with no clear answers available, writes Steve Meyer for the National Hog Farmer.Somehow, “A whole lot!” just doesn’t seem to suffice as an answer to the question of how many pigs have been lost. And I fear the numbers I have produced in recent weeks are little, if any, better.

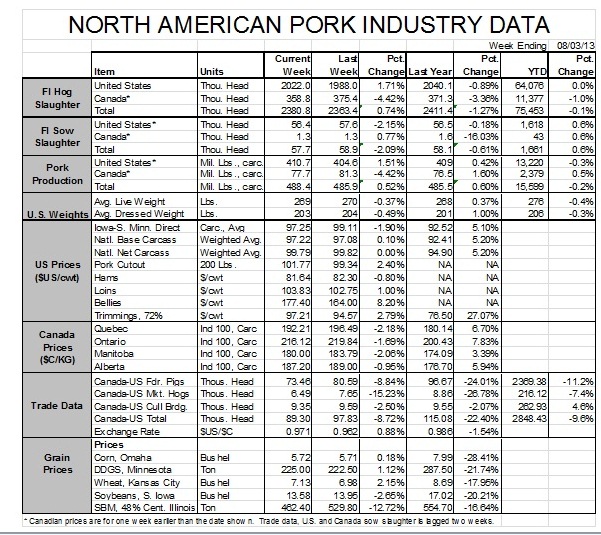

Figure 1 is a chart that I have used a few times recently to provide some context for pig losses since PED broke in April. I arrived at these numbers by using “accession” numbers from the summary first compiled by the American Association of Swine Veterinarians and now by the National Animal Health Laboratory Network, a system run by USDA’s Animal Plant Health Inspection Service. The summary, with data from two weeks past, is updated weekly and is available at www.aasv.org.

What started as a trickle has become, by these calculations, a significant number since mid-June potentially impacting slaughter beginning in mid-December by 2 to 4 per cent. The trouble is that the numbers may not be good at all.

I arrived at the losses by attributing every “accession” (which I think is veterinarian-speak for “case”) that was classified as sow/boar and suckling pig to a sow farm. I assumed that each sow farm was made up of 2500 sows that produced an average of 25 pigs per sow per year and that all pigs were lost for five weeks. Those assumptions could obviously be wrong, but I believe them to be pretty reasonable given today’s industry. The reader can be the judge of that. I derived the upper limit to the estimates by assuming that “other” accessions were also from sow farms. That is certainly not a guarantee but it is a possibility so I used it to derive an upper limit to the range.

The real trouble, though, is that no one beyond the attending veterinarian and producer knows the exact source of a sample or samples. An “accession” is in fact a “case” and there are usually multiple positive samples per accession. But more than one accession can be from the same farm if they are separated in time. That is, a follow-up positive test would be treated as a new “accession”. At least that’s what I think I understand. Further, if any farm or veterinarian is seeing newly-scoured pigs and concluding the problem is PED without submitting samples, the cases are not counted at all. So one problem overcounts and the other undercounts. What are the odds we are “SWAGging” our way into a correct figure? Pretty low, I fear.

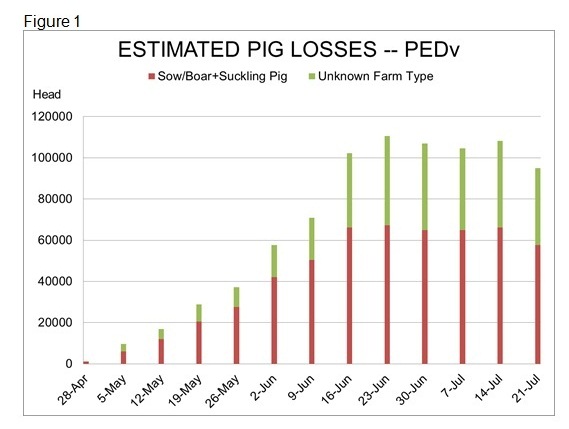

We could, of course, take the view of the technical analyst that all relevant and available data are embodied by a given market price. Using that view, one would look at the spot market for weaned pigs to see if the market is indeed reflecting either tighter supplies or higher demand from producers who have lost pigs trying to fill now under-stocked or empty barns. Figure 2, at first blush, might suggest one or both. Spot prices of 10-12-lb. weaned pigs made what appears to be their seasonal bottom in May. That is much earlier than normal and prices have risen steadily every week since then, reaching an average of $34.24 per head last week. The advance coincides well with the growing losses.

The trouble, of course, is feed prices are a major determinant of pig demand since that demand is “derived” from expected market hog values based on the cost of converting the pig to the market-weight hog. And new crop feed prices have been falling steadily over roughly the same period as pig losses have been reported. The reduction in new-crop corn and, to a lesser degree, soybean meal futures have taken Q4-’13 projected losses from the mid-teens per head back in April and May to just $2 to $4 per head according to my model based on Iowa State University’s (ISU) average Iowa farrow-to-finish operation. Q1-’14 margins are now projected to be positive by $3-$5 per head. That improvement would mean that feeders would very likely pay more now for weaned pigs even if PED had not happened.

The same technical analysis viewpoint would look to December and February Lean Hogs futures prices for insight. On Friday, the December Lean Hogs futures contract closed at $80.80, only $0.50 or 0.6 per cent higher than its close on 1 June. The February contract closed at $83.33, only $0.13 higher than its 1 June close. Do those changes mean the market hasn’t seen enough to be convinced or that other factors have outweighed PED losses in the collective action of traders?

So, will PED impact winter markets? I think it is likely but I wish I had better data from which to draw that admittedly-tentative conclusion. There are few requirements established for the type or amount of information to be provided with disease lab sample submissions unless, of course, the disease is more serious and thus classified as “reportable.” If this were foot and mouth disease, classical swine fever or African swine fever we would have much better information. But the costs to both individuals and the industry would, quite obviously, be extraordinary.

With that thought, I’ll decide to live with the present quandary; perhaps not happily but thankful that things are not far worse.