Porcine parvovirus (PPV)

Background and history

Porcine parvovirus infection (PPV) is a common and important cause of infectious infertility. PPV is a robust virus that multiplies normally in the intestine of the pig without causing clinical signs and is ubiquitous in pig populations world-wide. PPV is one of the organisms listed as responsible within the Stillbirths Mummification Embryonic Death and Infertility (SMEDI) syndrome.

In larger herds it is almost certain to be present and is an infection you have to live with and manage, rather than try to eliminate. In smaller herds with a previously PPV positive pig, it may or may not have died out.

Most viruses do not survive outside the host for any great length of time, PPV is unusual in that it can persist in the environment for many months and it is resistant to most disinfectants, and the most likely reason as to why is widespread and difficult to eliminate.

PPV is harmless to humans and other farm animals and is not a food safety risk.

Clinical signs

In acute outbreaks of the disease the infection itself causes no clinical signs other than the presence of mummified piglets, 3 to 16cm in length, at farrowing. Once inside the womb PPV spreads slowly from one foetus to another and as a result the sizes of mummified pigs will vary within the litter, and depending upon the gestation age when the sow became infected, some may live.

Other indicative observations are:

- An increased numbers of stillbirths. These are associated with the delay in the farrowing mechanism which occurs because of the presence of mummified piglets.

- Small litters associated with embryo loss before 35 days gestation.

- An increase in low birth weight piglets but neonatal deaths are not affected.

- Small mummified piglets in the afterbirth present.

- Abortions associated with PPV are uncommon.

- Increased returns to oestrus increase due to total embryo absorption before 35 days.

- Sporadic cases of individuals within a herd are usually confined to newly purchased naïve gilts or sows.

- Reduced efficacy of the vaccine in gilts as the maternal immunity may persist up to 7 months of age in the live piglets but only in a few gilts – which can interfere with the vaccine response.

- In larger sero-positive (antibodies present to PPV) herds up to 50% of gilts may be sero-negative at the point of mating.

- No other signs of ill health in the breeding females.

- No vaccination programme in place.

Clinical signs unlikely to be observed with PPV include:

- Long standing infertility (returns to service/oestrus) affecting all gilts and sows within an existing herd.

- Discharge from the vulva associated with returns to oestrus.

- Repeated returns to oestrus in individual sows.

- Mummification of single piglets within a large litter - these result from lack of uterine space and are a natural feature of breeding in multiple birth species.

- Abortions - unless the sow aborts a whole litter of mummified pigs

In larger herds with multiple farrowing, the acute disease lasts for around 2 months, wanes for a month and further incidences of mummified piglets for another month. PPV can take up to 4 months to infect all of the sows in a previously uninfected herd. Such episodes are likely to occur in non-vaccinated herds every 3-4 years and arise because virus circulation ebbs and flows. During periods of low or no PPV cases a susceptible population gradually emerges.

Interestingly, sows that have a complete foetal death may experience a pseudo-pregnancy. In some cases the sow reaches the point of farrowing with normal udder development, even to the extent of producing milk, but there are no live births. Here, an injection of prostaglandin is required to instigate farrowing which expels the mummified piglets present inside the womb. These animals would not otherwise farrow because live foetuses are necessary to initiate farrowing.

Predisposing factors

The immunological status of the herd i.e. no immunity is the predisposing factor. In PPV positive herds that mix gilts before mating age with either PPV positive pigs, or keep on ground recently occupied by positive pigs, then immunity will be present when they are mated later on. The breeding stock within the herd has recovered previously from PPV then they will have immunity for the rest of their life.

In small herds however the PPV may die out and the new gilts and sows in the herd will be susceptible. You will also need to consider if the virus has circulated completely through the herd, and if you have pens of naïve pigs.

The most effective way to ensure your herd is protected is to vaccinate all stock and failure to vaccinate, faulty vaccination techniques or storage can leave your herd susceptible. Also vaccinate boars as they can shed the virus in their semen.

Diagnosis

In the absence of any other signs of illness in the breeding females, PPV disease can be suspected by increases in variable sized (3 to 16 cm length) mummified pigs and small litter sizes.

For a laboratory diagnosis of a current infection in your herd the mummified piglets can be examined using a Fluorescent Antibody Test – antibodies to PPV are labelled with a fluorescent dye which binds to the tissue from the mummified piglets and glow under a UV light. Submit small mummified pigs (less than 16 cm) from small litters to a laboratory for fluorescent antibody tests. These will confirm whether the foetus has died from PPV infection or not.

Serology (looking for PPV antibodies in the serum) will not help diagnosis of current disease because many sows are positive and normal. If early in the suspected PPV case, ‘paired sera’ can collected a week apart to look for a sharp increase in antibody levels.

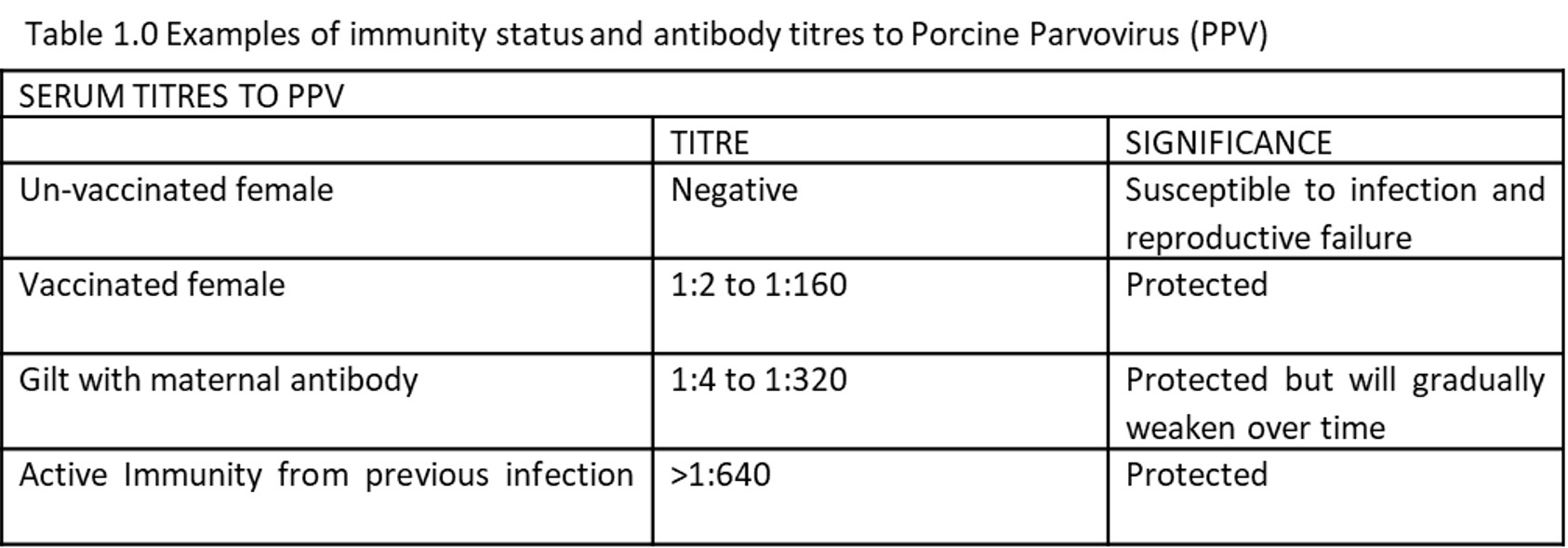

You can use serology to determine if the pig has immunity to PPV [Table 1.0]. PPV infection results in high antibody levels in the serum which persist for long periods. The detection of antibodies means that the pig has either been exposed to PPV previously (not necessarily associated with reproductive disease) or has been vaccinated. Antibody levels are measured in “titres” which is the dilution of the antibody to which it can still be measured by the test; so a titre of 1:640 means the sera can be diluted 1 in 640 and still be detected, whereas 1:2 means the sera can only be diluted 1 in 2, after that no antibodies can be detected.

High titres do not necessarily mean you have a greater protection against PPV as the circulating levels are a ‘background memory’ which are ramped up in production should the individual be exposed to PPV again.

Blood sampling all the sows in a herd on one occasion only indicates the percentage of animals that have been exposed to PPV previously and which ones are susceptible. Once an animal has been exposed to PPV it remains immune for the rest of its life.

Do not assume that all mummified pigs are caused by PPV infection. This is often not the case. PPV is quite different to Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome (PRRS) infection, which kills the foetus only after 70 days of age inside the womb and therefore very late mummified pigs are seen in this disease.

Cause

PPV is most often transmitted either by mouth or through the snout, passing into the intestine where it multiplies and subsequently passed out in faeces. When a pig becomes infected for the first time there are no clinical signs. Boars may also infect a sow at the time of mating via their semen.

To understand the role of PPV in reproduction it is important to realise that reproductive infection usually occurs without disease. In a naïve (not previously exposed or vaccinated) pig, it takes 10-14 days from first infection for PPV to cross the placenta and kill the piglets selectively inside the uterus. If a foetus is infected at less than 35 days of age, before there has been an opportunity for bone development, death results, followed by complete absorption although a very small litter of 1-2 piglets is possible if embryonic death occurs after day 14 gestation and before day 30. If infection takes place between 30 and 55 days of pregnancy the foetuses die and they become mummified. From 70 days gestation the immune system of the piglet has started to develop and it can therefore respond and protect itself from the virus, so if pregnant gilts or sows are infected for the first time after approximately 56 to 60 days gestation there is little evidence of disease. Occasionally, piglets born that were infected very late in pregnancy may show no prenatal damage, but be born dead, thought to be caused by a slow or disrupted farrowing. ` .

Prevention

PPV cannot be eliminated from a herd so management and prevention of acute cases should be the aim. Routine vaccination of gilts and boars prior to entering the breeding herd plus yearly boosters of all pigs should be sufficient to ensure the herd is protected. However, there is research to show that if the infected breeding female has been vaccinated or been exposed to PPV at some time in the past, then when exposure to PPV takes place, there is rapid re-stimulation of the immune system (within 5-7 days). This is sufficient to prevent disease and to stimulate a permanent immunity.

If you have an unvaccinated herd and you get an acute outbreak, immediately vaccinated the breeding herd to prevent an infection in the susceptible pigs. It takes 10 days for the first dose of vaccine to take effect and a second dose to prime the immune system is rarely required to provide protection. The first dose will prime the immune system and a low level of antibody is produced (1:64), the annual booster or exposure to PPV will normally be sufficient to protect the unborn litter as it takes 10-14 days to cross the placenta following infection.

Treatment

There is no treatment.