Zinc oxide use is going away in the EU – what can replace it?

New US swine research offers insights into replacement strategies for ZnO

The EU regulatory oversight is due to concerns about heavy metal accumulation in the environment and the potential for antimicrobial resistance. In a swine market without use of pharmacological levels of ZnO, what strategies can be incorporated to control post weaning diarrhea and maintain growth performance shortly after weaning?

Zinc is a heavy metal element that serves many biological purposes in livestock. Young pigs require around 100 parts per million (ppm) in the diet, due to the involvement of zinc in various enzymes, immunity and nutrient metabolism. Zinc also protects a young pig’s immature gut by reducing pro-inflammatory mast cells within the gut and to help maintain normal GI tract morphology.

Zinc contains antimicrobial properties and can increase feed intake through brain-gut peptide regulation. Zinc is commonly fed in swine diets at 2,000 to 3,000 ppm in the first few weeks after weaning, with the purpose of helping control post-weaning diarrhea and improving gut performance.

Strategies to achieve growth performance without ZnO

Several nutritional approaches could be used to potentially reduce the incidence of post-weaning diarrhea:

- Reduction of dietary crude protein

- Insoluble fiber post-weaning

- Feed additives

- Avoid excess dietary iron - promotes bacterial proliferation which can further exacerbate post-weaning diarrhea

“Nutritional approaches alone are not likely to result in the desired level of performance in a world without zinc oxide,” said Gebhardt. “Other approaches may be beneficial if used in combination, including maintaining a high health status within both the sow and wean-to-finish populations. If healthy pigs are weaned into a clean environment with few multifactorial disease issues, post-weaning diarrhea may be much less of an issue. Additionally, increasing weaning age may be beneficial to ensure that pigs are robust at weaning, start well on feed and are set up for success in the wean-to-finish period.”

A clean environment is critical along with having a dry, draft-free environment post weaning. Control of post-weaning diarrhea without the use of ZnO and without routinely using antimicrobials must be accomplished through a combination of management and nutritional factors.

“No single silver bullet will be successful to replace ZnO,” he noted.

Reduction of dietary crude protein

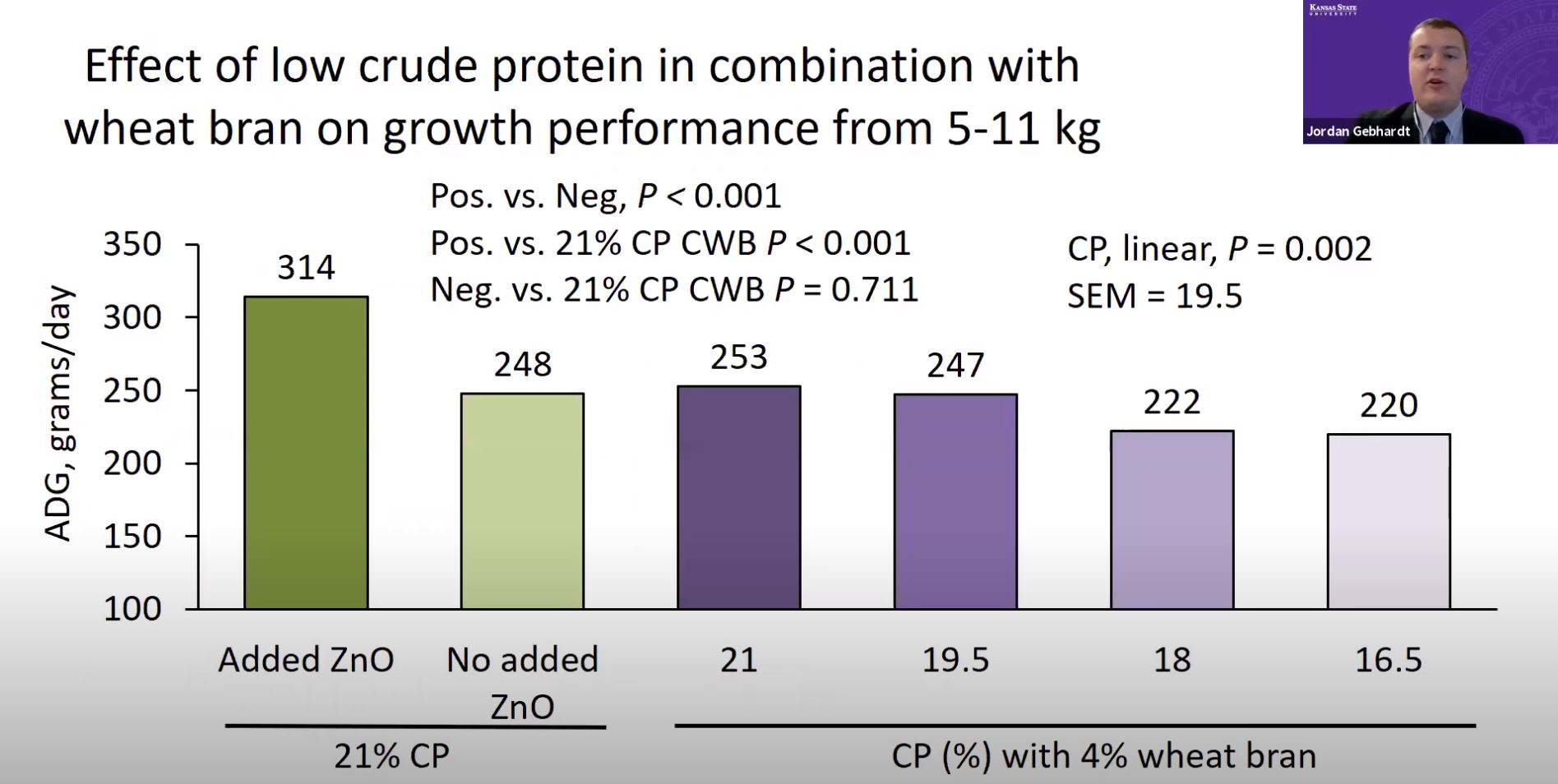

In a study looking at dietary crude protein levels, pigs were fed from 5 to 11 kilograms of body weight, with a 21% crude protein diet with and without ZnO added. In the added ZnO treatment, ZnO was included at 3,000 parts per million in the phase one diet, and 2,000 parts per million in the phase two diet. Additional treatments included diets formulated with 4% dietary course ground wheat bran with no added ZnO. These diets were formulated with decreasing levels of dietary crude protein ranging from 21% down to 16.5%, and they were formulated to a maximum digestible lysine to digestible crude protein ratio of 6.35%, so as dietary crude protein decreased, so did the SID lysine content.

The data shows a positive ZnO response relative to no added ZnO in the diet. The data deminstrate that the 21% crude protein diet with no added ZnO and 21% crude protein diet with 4% course ground wheat bran resulted in similar levels of average daily gain. As crude protein and SID lysine content decrease so does the average daily gain in a linear manner.

© J. Gebhardt, Kansas State University

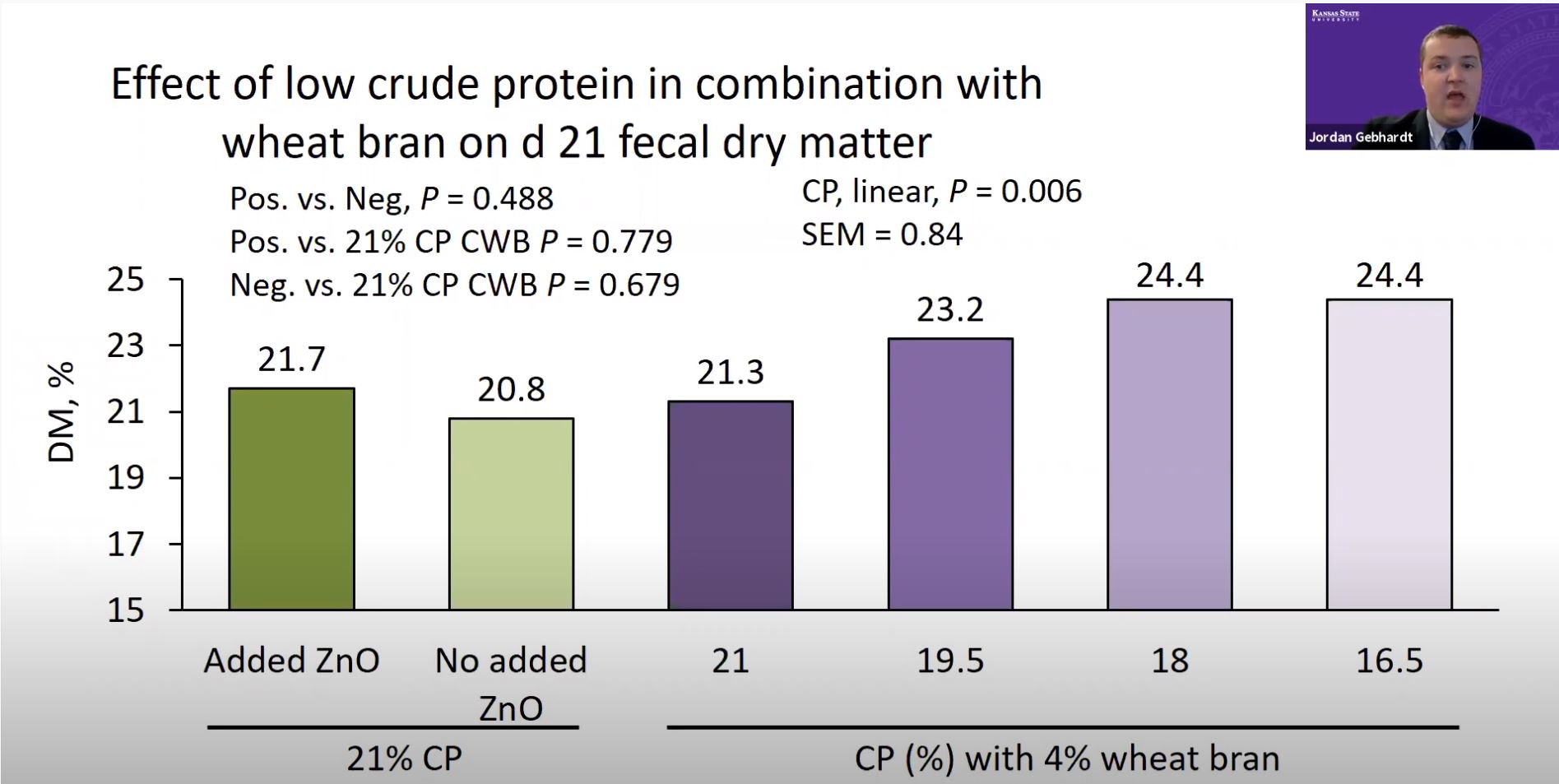

“When we look at this outcome, the stools become more firm or dipped fecal dry matter becomes greater when reducing the dietary crude protein level,” he said. “The fecal dry matter is not a direct outcome which generates revenue for a producer, however, the study illustrates the concept that reducing dietary crude protein and amino acid content can result in firmer stools. Feeding greater levels of dietary crude protein in nursery diets results in greater levels of undigested protein in the hindgut, which in turn, offers a greater amount of substrate available for the proliferation of pathogenic bacteria which can increase the risk for post-weaning diarrhea.”

The recommended nutritional approach for these early nursery diets is to feed a low crude protein, amino acid fortified nursery diet, which minimizes the inclusion of soybean meal and other specialty proteins, while meeting the specific amino acid requirements using feed-grade amino acids.

© J. Gebhardt, Kansas State University

“These formulation strategies allow us to reduce the occurrence of clinical scouring or post-weaning diarrhea, while maintaining an effective and cost-effective nursery program,” Gebhardt explained.

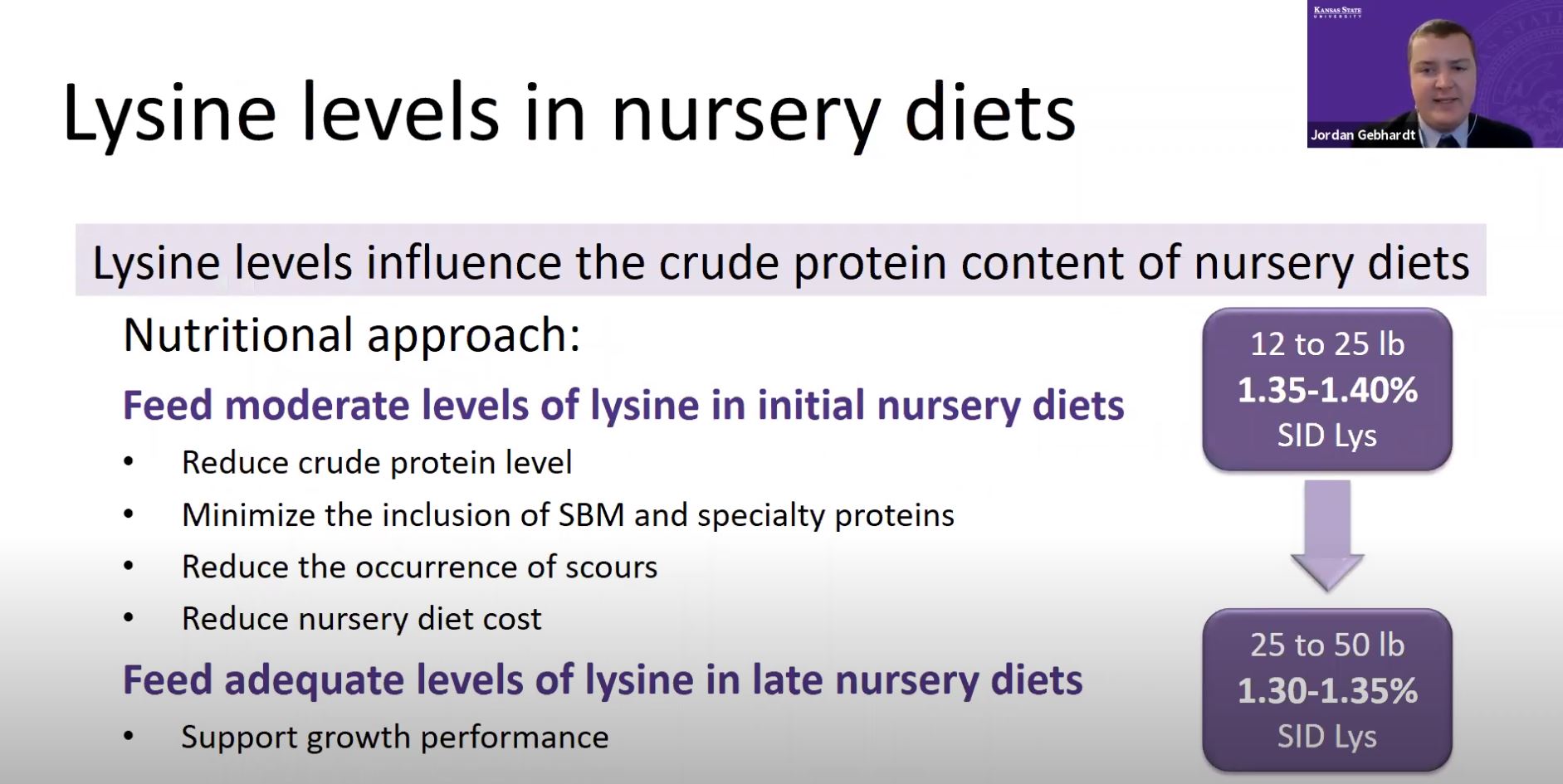

“Taking this step further and focusing specifically on lysine, our recommendation would be to feed moderate levels of lysine in early nursery diets. This allows for the reducing of crude protein levels, thereby reducing inclusion of soybean meal and other specialty proteins, which can reduce the occurrence of scours and reduce diet costs. Later in the nursery period, ensuring adequate lysine is provided to support growth performance is critical as the pigs really begin to increase their rate of growth, and then late-nursery and early grow-finish periods.”

© J. Gebhardt, Kansas State University

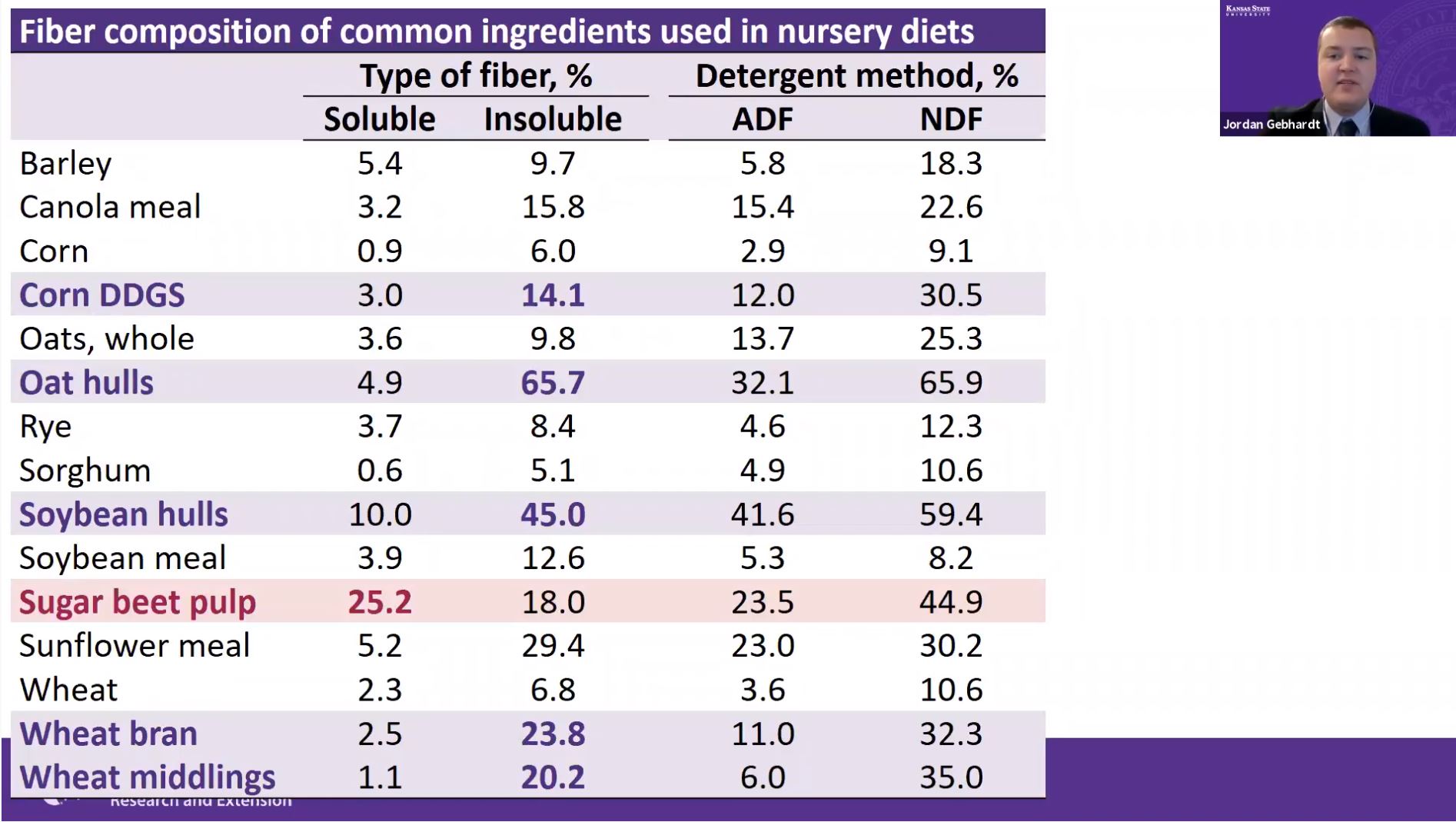

Soluble fiber vs. insoluble fiber

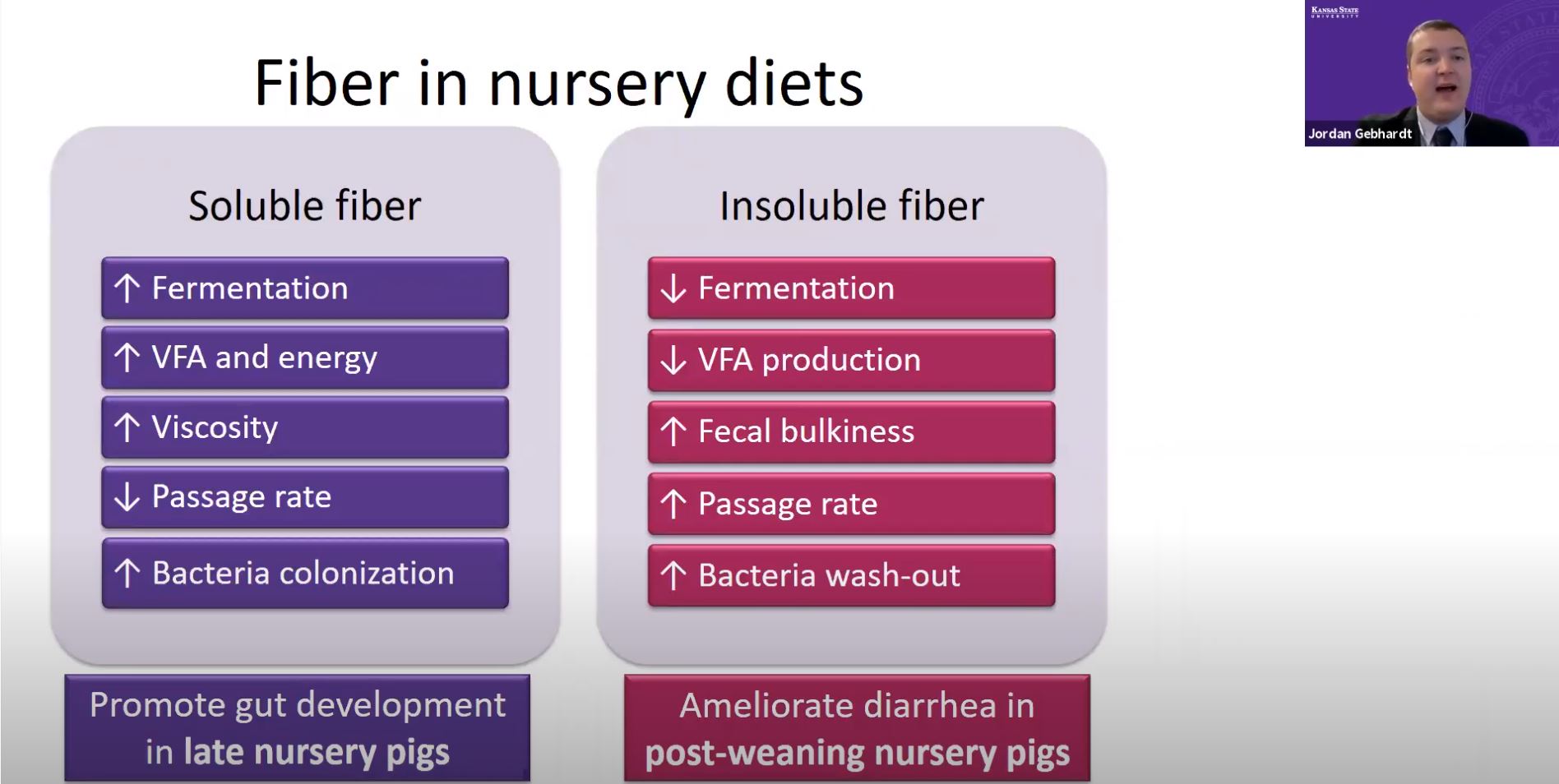

Soluble fiber can increase the fermentation within the hindgut, which increases fatty acid production and energy utilization. Soluble fiber can increase the scarcity of digestive material, reducing passage rates which allow for increased bacterial colonization. Soluble fibers included in the late nursery diets can promote gut development, according to Gebhardt.

© J. Gebhardt, Kansas State University

“However, when we're thinking specifically about early nursery diets trying to reduce bacterial overgrowth and reduce the growth and proliferation of pathogenic bacteria, insoluble fiber can have advantages,” he explained. “Insoluble fiber can reduce the fermentation and reduce VFA (volatile fatty acid) production within the hindgut.”

Insoluble fiber can increase the fecal bulkiness, increasing the passage rate and increasing bacterial wash out. Bacteria wash out reduces the ability for those pathogenic bacteria to adhere to the lining of the GI tract which can help reduce the negative impact and performance of post-weaning diarrhea shortly after the time of weaning.

Insoluble fiber early in the nursery stage could include ingredients high in insoluble fiber like oat hulls, soybean hulls, wheat bran, as well as wheat middlings.

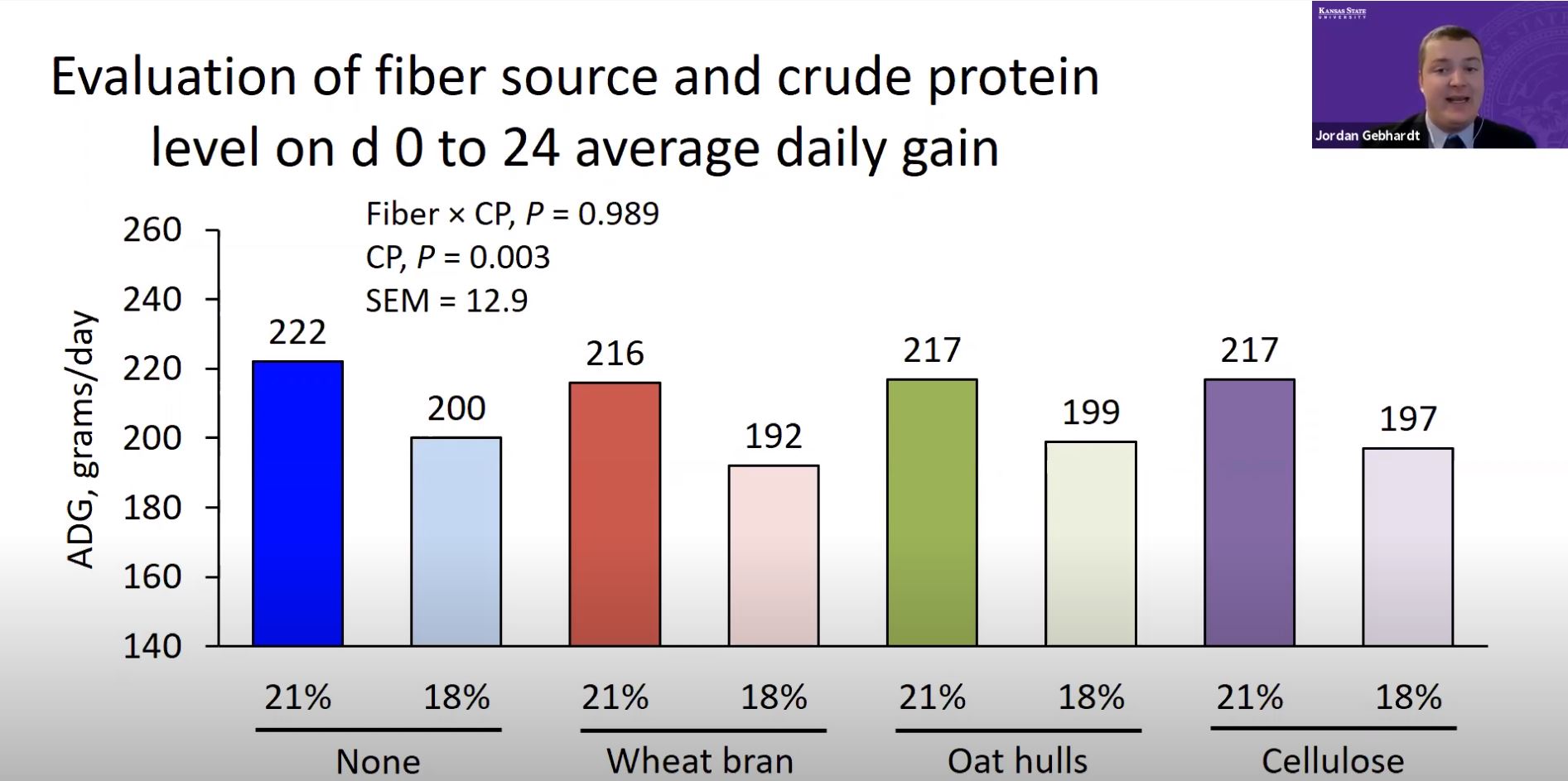

In a study where dietary crude protein and the fiber source were evaluated, three fiber treatments were used in addition to a series of diets with no added dietary fiber. The three fiber treatments included 4% added with bran, 1.85% added oat hulls, and 1.55% added cellulose to balance for dietary insoluble fiber content across the three fiber sources.

Additionally, two crude protein levels were evaluated at 21% and 18%, which represent 1.4% and 1.25% SID lysine in phase one, and 1.35% and 1.25% SID lysine in phase two. There was no evidence of a fiber source by crude protein interaction, and lower dietary crude protein and SID lysine content reduced average daily gain. There were no observed differences with respect to fiber source within this experiment for our average daily gain.

© J. Gebhardt, Kansas State University

Fecal dry matter at the conclusion of the treatment diets showed the pigs fed insoluble fiber from added cellulose resulted in greater fecal dry matter compared to no added fiber and 4% added wheat bran.

“To summarize the impact of insoluble fiber and in being included in early nursery diets, there is evidence that insoluble fiber in early nursery period may be beneficial by increasing fecal passage rate, which reduces the ability for pathogenic bacteria to proliferate and adhere to the lining of the GI tract,” he said. “In current studies, we can see an increase in fecal dry matter but did not necessarily see a benefit in growth performance outcomes under the current set of conditions.”

Feed additives

Feed additives can improve growth performance in the early nursery period if ZnO is not available at pharmacological levels, including copper which is commonly fed in the late nursery stage but could be incorporated earlier if ZnO use is limited.

“Other sources of zinc could be explored such as zinc nanoparticles which would allow a similar efficacy and impact on physiological functions for many of the types of activities that zinc is involved with in the body, albeit at a much lower level included in the diet,” he noted.

Other feed additives could be explored like dietary signifiers, fatty acids, pre and probiotics, as well as specific feed additives that may have antibacterial activity within their mechanism of action, according to Gebhardt.

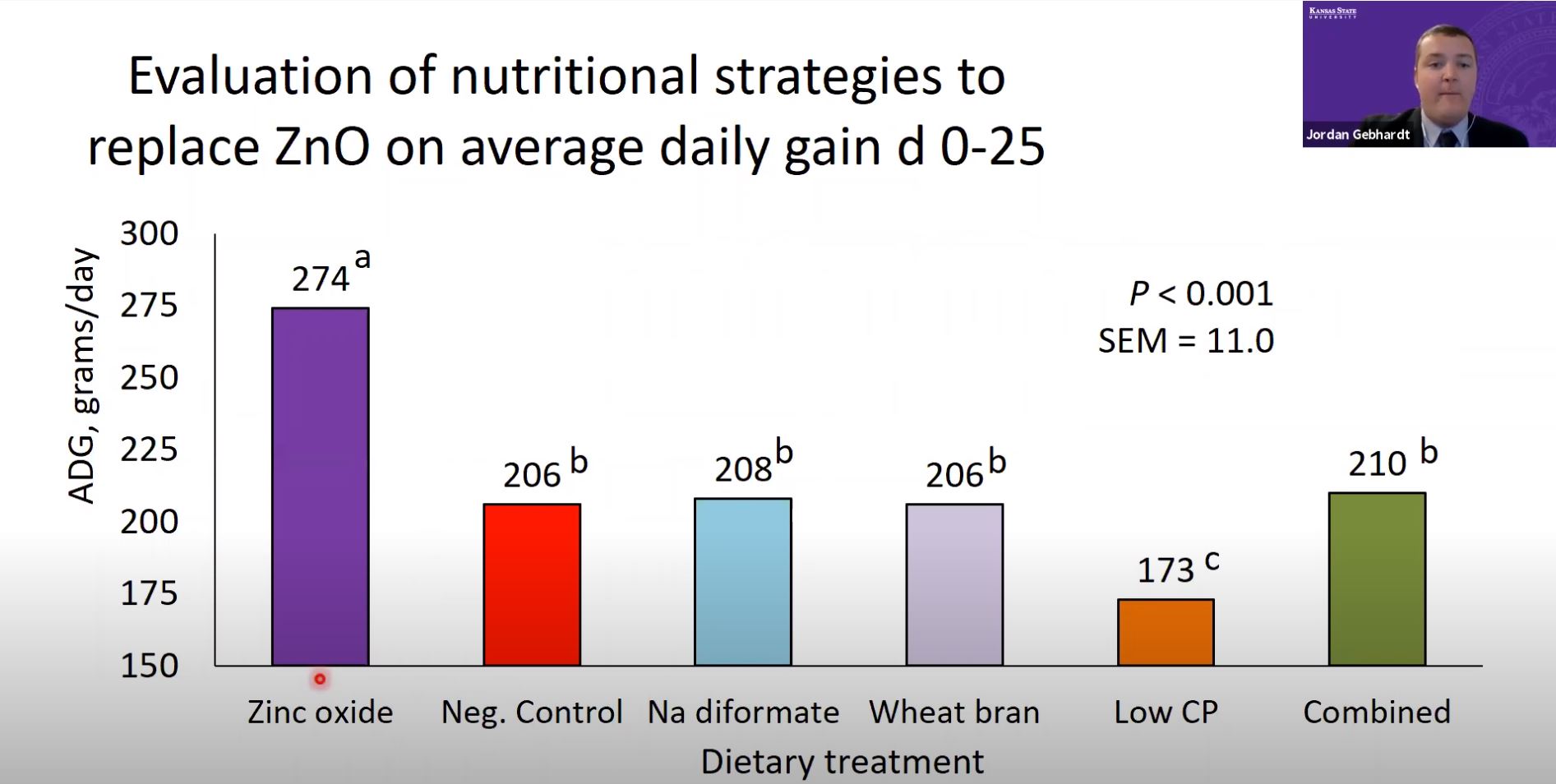

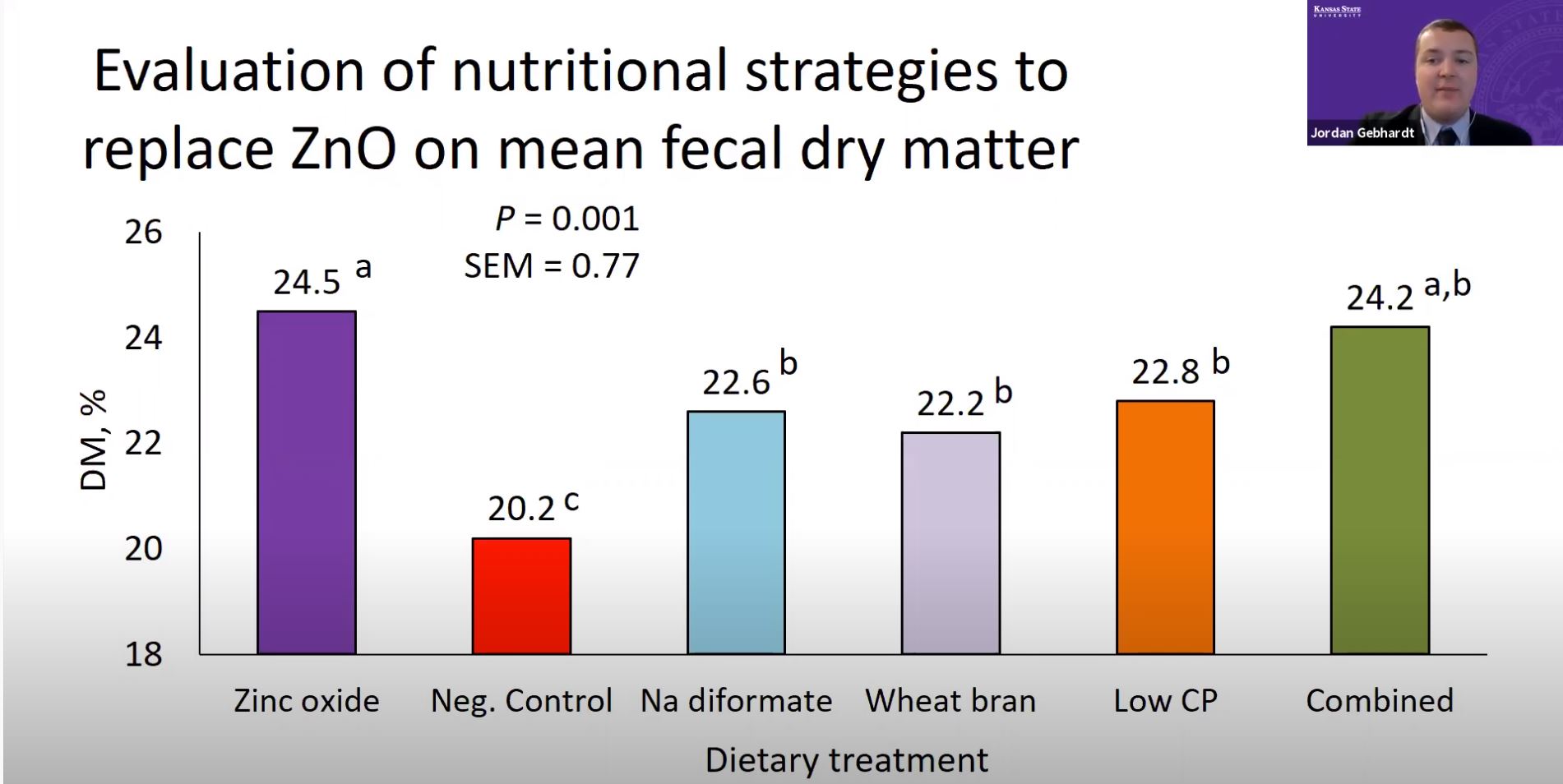

In a study using a positive and negative control, both were formulated to 21% dietary crude protein with ZnO at 3,000 parts per million of zinc in phase one, and 2,000 parts per million of zinc in a phase two. The negative control had only basal levels of added dietary ZnO, no added dietary ZnO and only basal levels of dietary zinc. The other treatments consisted of the negative control plus 1.2% sodium-diformate, the negative control plus 4% quartz brown wheat bran and reduced dietary crude protein diet, which was formulated to 18% crude protein. A combined treatment consisted of 18% dietary crude protein with 4% added wheat bran plus the dietary signifier.

© J. Gebhardt, Kansas State University

The data indicates a positive ZnO response, and the low crude protein diet resulted in poorer average daily gain compared to the 21% crude protein negative control diet.

“Interestingly, when the 18% crude protein diet had 4% added wheat bran, as well as the sodium-diformate, the growth performance was increased to a level equal to that of the 21% crude protein treatments,” he noted. “The combined treatment had 18% crude protein and it resulted in similar growth performance to the other treatments that had 3% greater dietary crude protein. When looking at mean fecal dry matter, the combined treatment had fecal dry matter similar to the positive control ZnO treatment. All strategies had greater fecal dry matter compared to the 21% crude protein no ZnO negative control treatment.”

© J. Gebhardt, Kansas State University

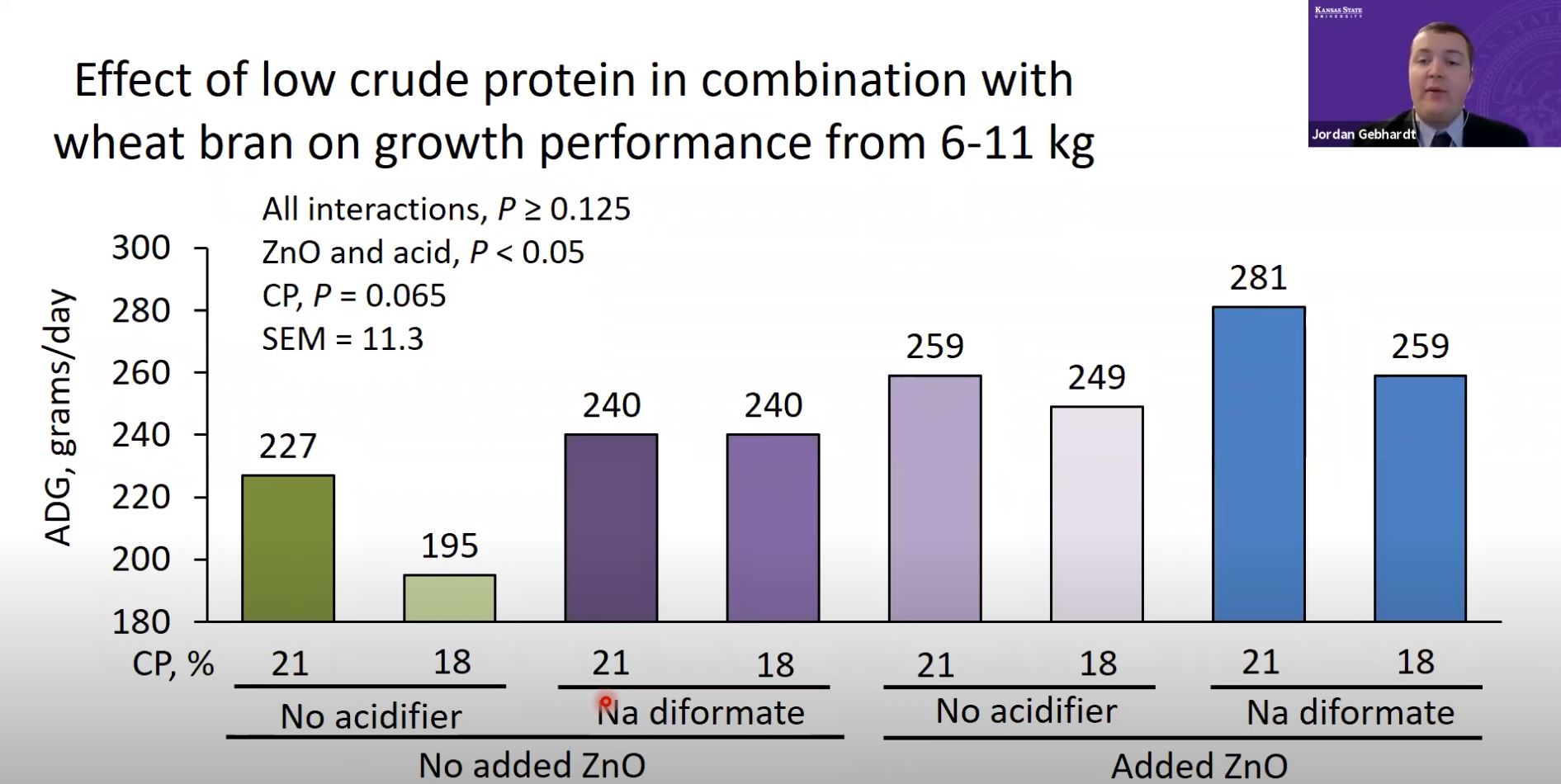

In another study designed to be two-by-two-by-two factorial, with or without ZnO, with or without 1.2% sodium-diformate and two levels of dietary crude protein, 21 or 18%, there was no evidence of any interactions for average daily gain during the treatment period. However, both the ZnO and sodium-diformate, resulted in greater average daily gain.

© J. Gebhardt, Kansas State University

The future of ZnO use

“Unfortunately, there is no clear answer or single strategy to replace pharmacological levels of ZnO in our early nursery diets. If future regulatory restrictions are placed on the use of ZnO in the US, a multi-factorial approach would be the most effective strategy to control post-weaning diarrhea and improve growth performance without using feed-grade antimicrobials for the treatment of clinical post-weaning diarrhea,” Gebhardt noted.

Zinc oxide is an important tool used in early nursery diets to help control diarrhea and pharmacological levels of zinc oxide are fed for 2.5% to 3.5% of all the feed that a pig is fed during its lifetime, he noted.

“Concern of heavy metal accumulation in the environment and antimicrobial resistance are very important, but it's important to recognize the limited duration in which these high levels are fed. The short duration allows for dilution effect over time as that pig consumes the largest amount of feed much later in the nursery and then throughout the finishing phase,” he said.

“The US swine industry must remain judicious in the use of ZnO and incorporate where appropriate to maintain animal health and wellbeing. But we must avoid overuse and continue to advocate for continued access to this technology to avoid regulatory restrictions in the future, which will negatively impact the wellbeing of pigs in the early nursery stage by limiting the use of dietary zinc oxide.”