Why gilt health is key to managing Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae

Disease is the single greatest destroyer of profitability in pig production. It affects all four production drivers of profit.by Eduardo Fano, DVM Boehringer Ingelheim, Swine Technical Manager for FLEX™ Family

Disease is the single greatest destroyer of profitability in pig production. It affects all four production drivers of profit: average daily gain, feed conversion efficiency, meat quality characteristics and death loss.

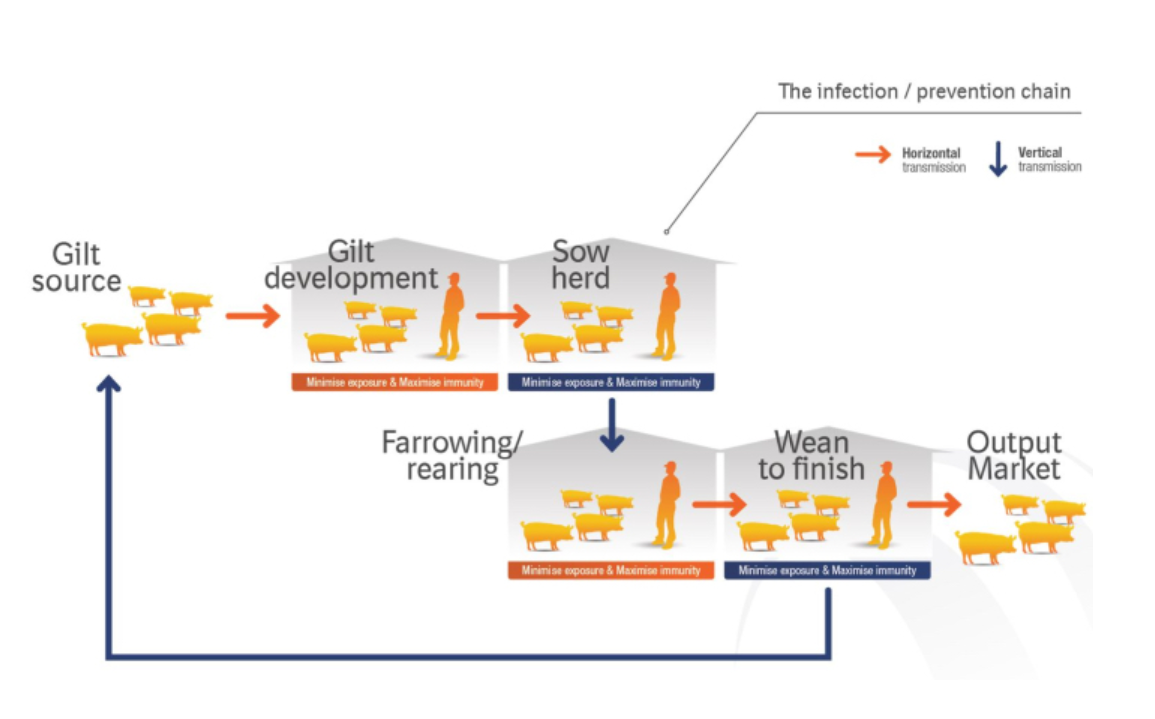

To help producers better manage disease, Boehringer Ingelheim (BI) has developed a way to bring together new and existing knowledge in swine disease management through the Infection Chain™ and Prevention Chain™. This concept offers a systematic approach to disease control that can be applied to almost any infectious disease.

The INFECTION CHAIN and PREVENTION CHAIN connect epidemiological events (infection chain) that can occur between the different production phases by using logical chain thinking to create multiphase intervention strategies (prevention chain). Only by understanding how a swine herd is linked together can we begin to identify disease transmission patterns.

Identifying the links that form the infection chain

The concept of the INFECTION CHAIN and PREVENTION CHAIN was originally proposed by myself and fellow BI veterinarians Dr. Brian Payne (now with Pipestone Veterinary Services) and Dr. Edgar Diaz, to address Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae (Mhp) and porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS). It starts with examining epidemiological pieces of the infection chain throughout the production process, including persistence of infection, shedding patterns, vertical transmission and lateral infection. The chain starts with gilt development and introduction into the sow herd, and ends in grow-finish populations or reconnects with a new link to gilt production.

The INFECTION CHAIN and PREVENTION CHAIN rely on the simple concept of an infection or disease management equation that balances minimising exposure with maximising immunity. To successfully control a disease, we need to minimise exposure through biosecurity measures (internal or external), flow management and use of antimicrobials (systematic use) where necessary. At the same time, producers need to increase protection in their barns by maximising immunity through vaccination.

Management of Mhp through use of the INFECTION CHAIN and PREVENTION CHAIN

Applying this concept to control Mhp infections in production systems has led to an understanding of the important role replacement gilts play in controlling the disease. Health challenges of incoming and recipient females need to be properly managed to avoid health issues and production disruptions in the herd. [1]

Consider the example of Mhp-negative gilts entering an endemically infected farm. We first need to recognise two important epidemiological features of the disease: long persistence and infectious period, and also low transmission rate. Because of these, the ideal method for gilt acclimation would be to receive negative gilts at a young age, and allow for effective exposure, disease development and recovery to take place before the first farrowing. [2]

For many farrowing operations, that might require the acclimation/exposure process for young females to start no later than at 100 days of age.1 Previously vaccinated gilts would start developing infection and shedding four to six weeks after exposure, and assuming shedding lasts almost 240 days, infection would need to be confirmed by 100 days of age to allow for total recovery (with no more shedding) by first farrowing, at around 350 days of age. By meshing the production process with the infection chain, overall control of Mhp could theoretically be achieved through uniform and controlled exposure of the reproductive herd by proper gilt acclimation.

Another common occurrence is bringing infected replacement gilts (active shedders) into a herd, which could lead to increased Mhp circulation in the sow herd, higher rates of sow-to-piglet transmission, and more piglets infected at weaning. In this example, initiating disease management protocols within the gilt population, including vaccination, strategic antibiotic treatments and early exposure time, can reduce the likelihood that infection will be expressed in wean/finish pig populations. [2]

References

1 Pieters M and Fano E. Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae management in gilts. Vet Record 2016;178(5):122–123.

2 Fano E and Payne B. Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae gilt acclimation and sow herd stability: Essentials to the systematic control approach. Proceedings. AASV Annual Meeting 2015;175–178.