Water quality: the winning formula for pig production

Fresh, clean drinking water is one of the most important things you provide to your pigs – and there’s more technology and innovation involved in getting it right than you might have thought.Clean drinking water is essential for the healthy growth and development of all livestock. While pig producers spend ample time working to get nutrition and feed just right, water often doesn’t get the attention it needs. But both play a key role in pig performance. In fact, water quality affects everything from feed intake and growth rate to feed efficiency and mortality.

Similar to humans, pigs’ bodies are made up mostly of water. In adult pigs, water represents 55 percent of total bodyweight, and water makes up 82 percent of a young pig’s total bodyweight. What’s more, the average pig will drink approximately 10 percent of its bodyweight each day, which means it will need a constant source of fresh water to meet its needs.

While there’s not a lot of research on water use in swine production, one excellent paper was presented at the 2010 Manitoba Swine Seminar. Written by University of Manitoba researcher Martin Nyachoti and co-authored by Elijah Kiarie from the University of Guelph, Water in swine production: a review of its significance and conservation strategies, provides an update on water use in swine production and suggests best management practices for conserving water.

North American swine producers obtain water from three main sources: well water from the ground, surface water from dugouts and pipeline water for public use. Water quality and the risk of contamination vary from one source to another. Surface water sources, wrote Nyachoti, have the highest risk of microbial contamination, while risk declines considerably with the use of sources like cisterns and natural springs.

When given poor-quality water, pigs will either decrease or increase consumption. Increasing consumption leads to increased slurry production, Nyachoti points out. “This is undesirable because it adds to the growing concern of manure disposal within the livestock industry and increases the cost of applying manure on the land,” he wrote.

“Furthermore, because animals must excrete any excess water consumed, their performance can suffer as energy, which could otherwise be used for growth and production, is expended on water excretion.”

Determining the quality of water

Water quality is determined by its inorganic and organic elemental makeup. The number of coliforms per millilitre of water, for instance, determines the level of water contamination by bacteria. According to an Alltech factsheet on water quality in pig production, a total of 50 colony forming units (cfu) is fine, but anything higher than 100cfu/ml requires treatment.

Inorganic compounds, such as nitrates and nitrites are also problematic in drinking water. Research by retired South Dakota State University professor RJ Emerick found that nitrites are 10 times more toxic than nitrates in monogastric animals such as pigs, and levels as low as 0.10mg/l of nitrite can impact overall performance. High levels of nitrites and nitrates are usually the result of exposure to nitrogen sources, such as fertiliser, animal waste and decomposing organic matter.

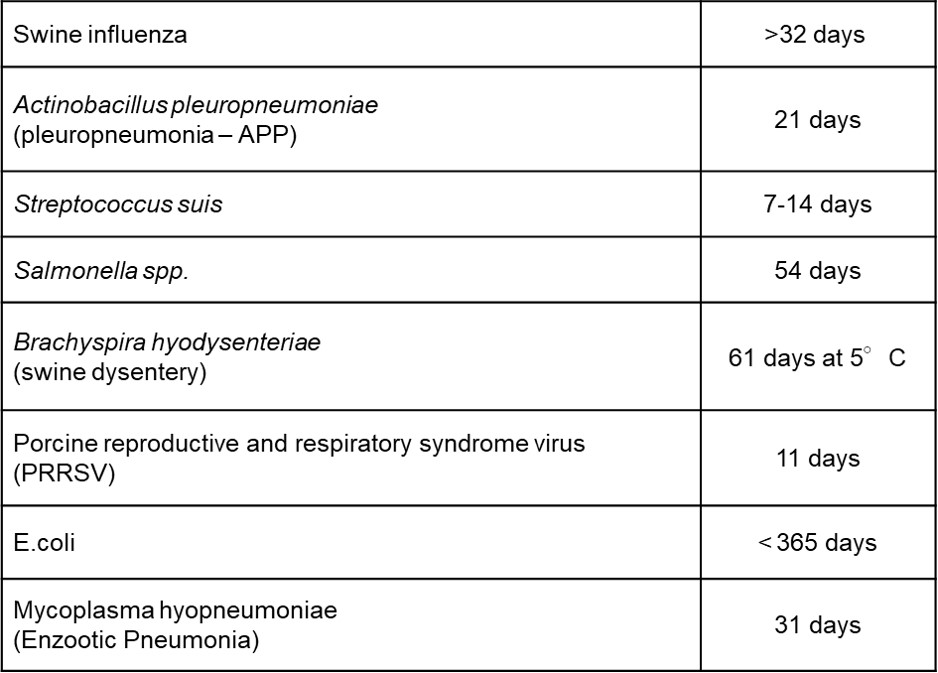

With contamination comes disease, especially when the contamination comes from manure. Research from the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA) in Canada shows that internal parasites and diseases such as leptospirosis and salmonella can be transmitted through manure-contaminated water. While some pathogens won’t survive long in water, others will. The chart below, courtesy of AHDB Pork in the UK, outlines how long pathogens associated with swine diseases can survive in water.

© AHDB Pork

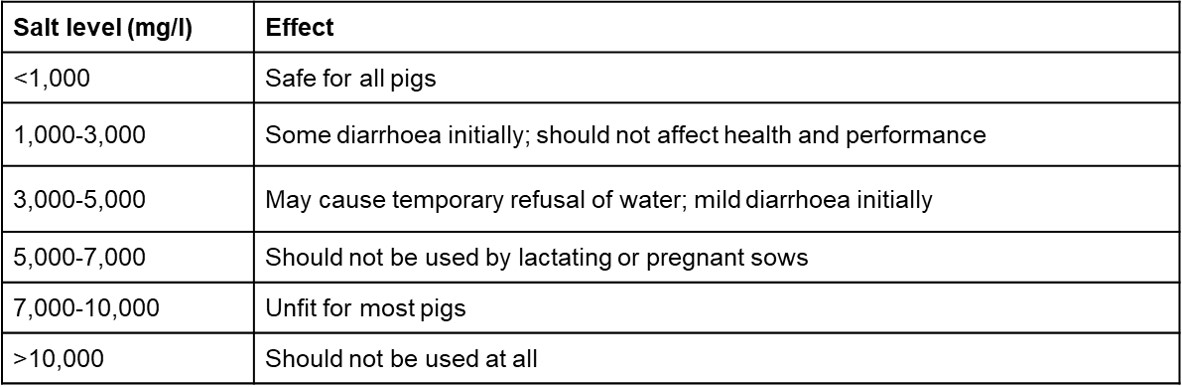

Salinity is also an issue pig producers will want to keep an eye on. Salinity is the measure of all salts that are dissolved in a given quantity of water. While Canadian guidelines suggest that salt concentrations not exceed 3,000mg/l, Australian guidelines suggest a maximum of 6,000mg/l. “Pigs can adjust to saline water if the adjustment period occurs over several weeks,” the factsheet says. “A sudden change from low- to high-saline water can cause death.”

© Canadian Council of Resource and Environment Ministers

Avoiding biofilm

Ensuring water quality goes beyond the water itself; it’s important to make sure the piping that delivers that water is also clean. Iron, manganese, calcium and magnesium all contribute to water hardness. Mineral content that is too high can cause leakages. In the presence of oxygen, these leakage points can become the perfect breeding grounds for microorganisms to form a biofilm. Not only can biofilm harm equipment, but it also gives off an odour, making the water less desirable, and can spread disease throughout the herd. Biofilm can be best described as a protective layer that shelters the microorganisms from elements in an otherwise hostile environment. Not only that, but biofilm is said to play an important role in the spread of antimicrobial resistance, as surviving microorganisms that hide in tiny nooks throughout the piping pass resistance genes on to the next generation.

There are plenty of products on the market to address this growing issue. However, one stands out from the rest, as it uses no chemicals. The CD-san Concept by Aumann Hygienetechnik was showcased at EuroTier 2018, the world’s largest trade fair for livestock production.

The CD-san Concept, when coupled with the Harsonic ultrasound system, enables thorough disinfection and cleaning when water lines are both empty and full. In the empty phase, the ultrasound system also amplifies the effect of disinfectants.

Installed between the drinking lines, the ultrasound device cleans deeper than chemical products, said Mieke Van Genabet-Harteel, CEO of Harsonic.

“Chemical products have their limits,” she said. “The problem is that they cannot go into the little micro cracks and the little corners because they are just flushed away, and that is exactly the location where resistant bacteria are.”

A transducer, which is mounted to PVC, is connected to a control unit. In situations where livestock are on the ground, two transducers are needed to treat 700-750m of waterline. Chickens in cages, for example, face less pressure, and only require one unit for every 750m.

“The biggest advantage is that you avoid the clogging of your drinking lines because people give a lot of additives and medication through their drinking water, and this all sticks to the biofilm,” explained Van Genabet-Harteel. “The biofilm is a sticky layer where everything is located and stuck to, and that’s what we take out.”

The product has been in testing since 2013, and the CD-san Concept won an Innovation Award for animal welfare at EuroTier 2018.