Tips to improve your handling for pig welfare and productivity

The way we handle pigs can have important consequences for their welfare and productivity.Pigs are regularly handled by stockpeople in commercial production systems for a variety of reasons. These interactions can be perceived as pleasant or aversive by the pigs, however due to the nature of modern production systems, most human-animal interactions are biased toward being aversive.

Opportunities for positive human-animal interactions, such as hand-feeding, patting and exploring, are limited, whereas negative human-animal interactions, such as the handling associated with painful husbandry procedures, weaning, social mixing or confinement are more common. Pigs will develop high levels of fear toward humans if the majority of human contact that they receive is negative.

Fear is well recognised as an important stressor for farm animals, and has been included in many welfare assessment programs, such as Welfare Quality. It can elicit just as great a stress response as a physical stressor, and is extremely unpleasant to experience. Fearful pigs can be identified by their avoidance behaviour towards a human, with greater fear associated with greater avoidance.

The magnitude of the avoidance response is also indicative of the magnitude of the stress response that the pig is experiencing due to fear. Fearful animals that cannot escape from a fearful stimulus, such as pigs in a pen, can develop a chronic stress response which will lead to reduced productivity and welfare. Research has shown that pigs can become fearful of humans after only 15-30 seconds of negative contact per day, so don’t underestimate the impact of handling techniques simply because they are brief.

High fear of humans in sows and gilts has been associated with reduced productivity in terms of the number of pigs born per sow per year, and in some studies, increased rates of overlays and stillborns. In fact, fear accounts for approximately 20% of the variation in reproductive output. This relationship is thought to be mediated by the chronic stress response, as the cortisol released during a chronic stress response can interfere with the hormonal cascade required for a successful conception and pregnancy.

The chronic stress response can also explain why high fear of humans in grower pigs has been associated with low growth rates. Cortisol can reduce metabolic efficiency by mobilising energy reserves through glycogenolysis. This energy mobilisation is associated with a reduction in muscle pH, and poor handling prior to slaughter has been associated with inferior meat quality and carcass bruising. In addition to these metabolic effects, chronic stress is also associated with poor health through immunosuppression, and fearful pigs are more likely to injure themselves during handling. Thus, reducing fear of humans in pigs can improve both welfare and production outcomes.

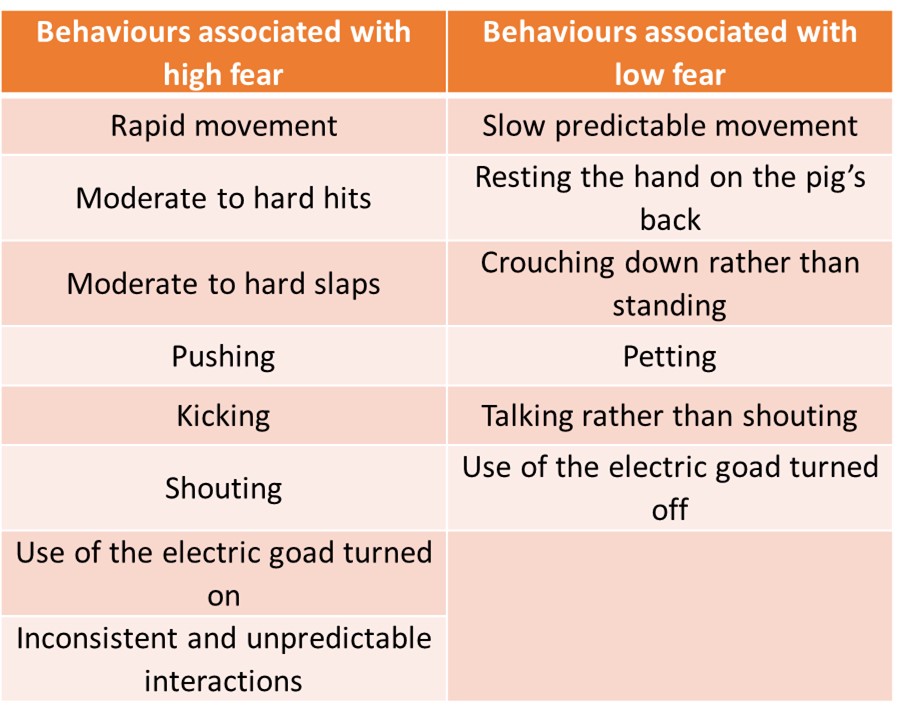

We can reduce fear of humans in pigs by decreasing the proportion of negative human-animal interactions that they experience. Research has shown that the human behaviours associated with increased fear are rapid movement, yelling, and the use of moderate hits and slaps (see table below). If these behaviours are used regularly and routinely, the pigs will become fearful of the stockperson. Positive or neutral interactions are ones that do not cause an unpleasant experience for the pig.

Studies that have successfully decreased fear in pigs have used behaviours such as crouching, talking gently, petting the pigs, and avoiding the use of forceful handling techniques. Obviously not all of these behaviours are practical in a commercial setting, so it is important to note that it is the proportion of positive to negative interactions that determines the quality of the human-animal relationship. By increasing the number of neutral or positive interactions, and avoiding negative interactions where possible, the human-animal relationship will be improved. In fact, when a stockperson training program (ProHand® Pigs*) was implemented to specifically target the human animal relationship on Australian farms, the attitudes and behaviour of the stockpeople improved, sows became less fearful and sow productivity tended to improve.

An interesting idea that is still in the preliminary research stage is the use of social and emotional contagion to improve the human-animal relationship. Pigs are social creatures that can learn from each other, and it may be more efficient under commercial conditions to develop a positive human-animal relationship with key individuals, such as farrowing sows or some of the piglets, who can then demonstrate low fear of humans to the rest of the litter.

In conclusion, the human-animal relationship has important implications for pig welfare and productivity. By targeting the attitudes and behaviour of stockpeople we can improve welfare through lower rates of fear, and improve productivity through lower rates of stress. In addition, the job satisfaction of stockpeople can be improved through better ease of handling, as fearful pigs can be difficult to move. While some negative interactions are a necessary part of farm life, the routine use of them need not be, and reducing the proportion of negative interactions should be an important goal for all stockpeople. After all, it doesn’t cost anything to change our behaviour, and it can have large benefits for pig welfare and productivity. So, when working with pigs, remember that it is the proportion of negative to positive interactions that determine the quality of the human-animal relationship, and always “Maximise your positives, minimise your negatives”!

*ProHand® is an original concept developed by Australian Pork Limited and the Animal Welfare Science Centre in 1996

For further reading on this topic, please refer to the following references:

Hemsworth and Coleman (2011). Human-livestock interactions. 2nd edition. CAB International. Wallingford, UK.

Tallet et al., (2018). Chapter 13. Pig-human interactions: Creating a positive perception of humans to ensure good welfare. Advances in Pig Welfare. Woodhead Publishing.