The ban on routine castration in Europe – is it progressing?

A ban on routine castration in Europe by the end of 2018? Will boar taint affect the sales of pork and what are the potential alternatives to surgical castration.A potential ban on routine castration in European pig herds looms with public and consumer concerns for welfare being supported by pressure from a number of governmental and non-governmental organisations. With the added economic benefits of raising boars rather than castrates, it appears the advantages to raising 'whole' pigs outweigh the losses. The Pig Site speaks to PIC's Craig Lewis to find out more.

What causes boar taint and how can we control it?

The one thing that we consistently find when examining boar taint is that the more we think we know, the less we really know.

The primary agents that cause boar taint are androstenone and skatole. These hormonal products, however, do not control 100% of the variance that can be observed in boar taint occurrence – even if we have low levels, we can still have high incidences of boar taint. To date, boar taint has been primarily controlled through routine castration of young males. For now, this is the best measure we have but we don’t know everything.

Androstenone and skatole are the primary components that researchers have associated with boar taint, though studies have shown that even cases of low concentrations of these hormones can have high incidences of boar taint

Boar taint is also subjective; androstenone can be detected by 90% of women but only 50% of men. I know that I cannot detect androstenone so it doesn’t impact upon my taste preference to eat meat that has boar taint.

One of the issues here with understanding who can smell boar taint and whether it needs to be mitigated is that we don’t have a true idea as to underlying incidences; it is dependent on how you’re testing for boar taint; and in the UK and Ireland, with slaughter weights being much lower than elsewhere in the EU, the concentration of boar-taint hormones will be lower as pigs are at an earlier stage of maturity.

Is the need to mitigate boar taint also dictated by the type of product that the meat is being used for?

This depends on the market you’re in – all markets are totally different and have distinct products that they use on a country by country basis.

Italy, for example, have to have pigs over 9 months of age, weighing over 160kg to enter into the parma market – prosciutto and parma ham being a protected regional product. They will have some exemptions from the castration bans or will be required to use analgesics, for example, because there’s no way you could carry intact males up to those weights.

Which countries continue to routinely castrate meat pigs?

As you would expect, the UK and Ireland for example are running entire male herds, without any castration. However, there are other countries within the EU, that are maintaining large herds, which continue to use routine castration. Denmark, for example, is a country where pretty much all of their pigs are castrated.

As we look at Europe today there is no real one size fits all, so any control over castration is going to be a very member state by member state process.

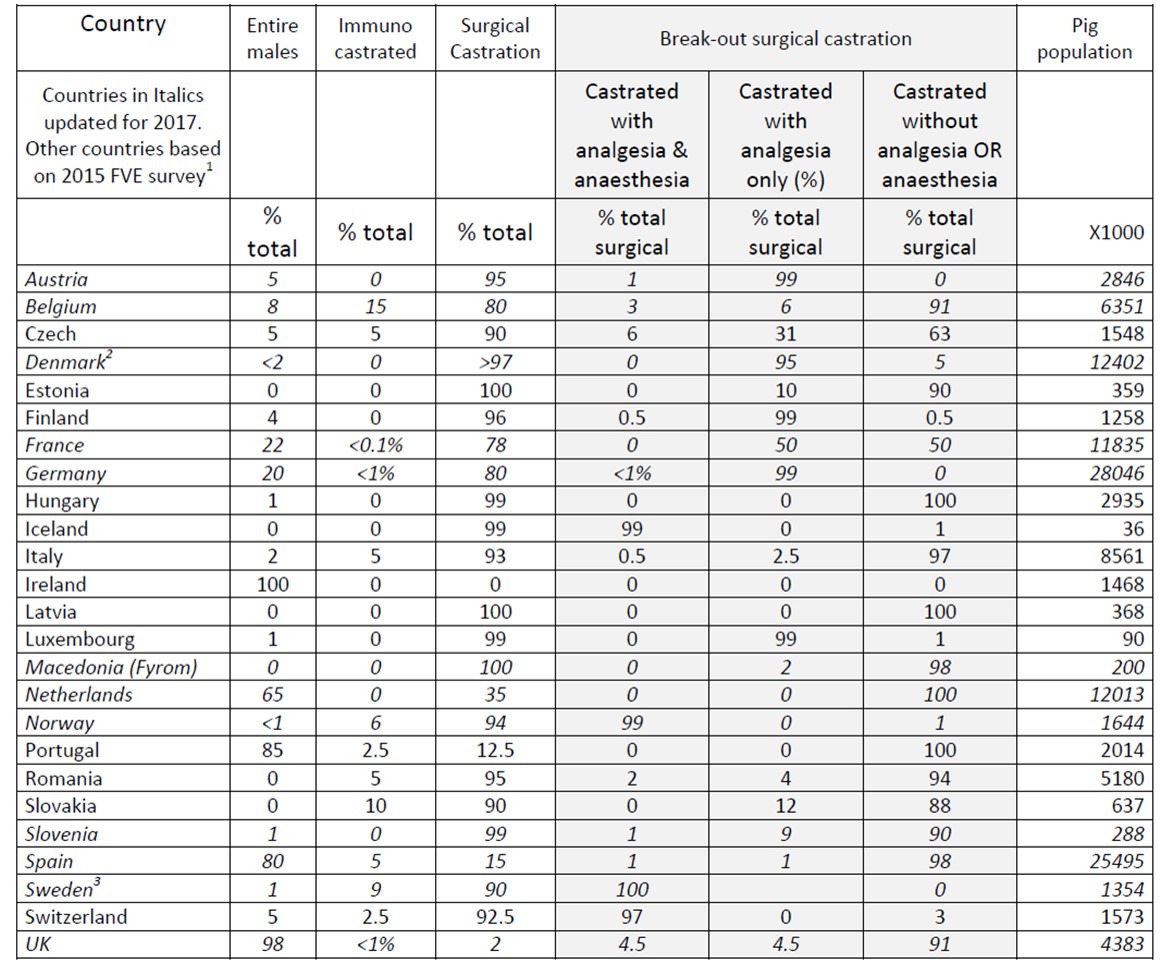

Castrations registered in table 1 are pretty much all surgical, with some exceptions to that rule – immunocastration is used in some instances.

Whether immunocastration is used or not, is subject to consumer demand and preference. There are instances where there is still a sense of unease surrounding immunocastration.

In my opinion, immunocastration is a solid and well-established technology, and, in terms of eliminating boar taint, it solves that one issue even if it opens up issues elsewhere – it certainly would reduce the pain and stress caused by castration on-farm which is predominantly where the welfare concerns lie.

Table 1: The percentages of entire males, immunocastrated and surgically castrated commercial piglets and methods of castration used in 24 selected countries (Second progress report 2015 – 2017 on the European declaration on alternatives to surgical castration of pigs).

1) De Briyne N et al, (2016) Pig castration: will the EU manage to ban pig castration by 2018? Porcine Health Management, 2:2.

2) Denmark is the largest exporter of weaners in the EU. Therefore, the column ‘pig population’ misrepresents the situations somewhat. The number of entire male pigs in Denmark is approximately 300.000 per year. This is less than 2 percent of the male pigs. See also a parliamentary question to the Danish minister stating that in 2016 production was 325.287 entire male pigs.

3) The presented percentage of immuno castrated pigs in Sweden is by some experts considered to be very high and not realistic, and by others to be low.

What are the implications for swine health and welfare through routine castrations?

There is certainly the perception that castration, on the whole, is a bad thing but this is predominantly driven by the lack of pain relief used when conducting castration procedures on many farms in Europe.

From a health perspective, any point at which you’re opening up the body, you are increasing the risk of introducing bacteria and other pathogens into the body. By not castrating, you are eliminating one of the methods by which disease can set into young pigs.

This said, you could argue that by keeping males intact and growing them to heavier weights at puberty, they may be more aggressive to each other and cause damage then, but it is all about balancing the pros and cons of farming practices.

When it comes to deciding where the ban will be applied, will there be exceptions around Europe?

There will probably be exceptions with specialist products, whereby they will either be allowed to castrate under strict conditions concerning days after birth and the use of pain relief, Iberico and Parma markets, for example.

The other course of events may be that the ban is not a true ban in the sense that castration will continue to be permitted but not without the use of analgesics during every single procedure, similar to how Denmark have been proceeding. Denmark have been circulating communications regarding proper castration training, and the type and dose of analgesics to be used.

Are there genetic ways to control boar taint?

You can look at this from two types of breeding: standard, and novel-type breeding.

Within PIC we have been able to capture data in the PIC-408 line, a Pietrain line, from which we can estimate breeding values on androstenone and skatole.

What we then can do is segment our population so we can siphon out those families that are at most risk of high incidences of those hormonal products. Those would be your high-risk animals whose offspring would have higher risk for boar taint.

By preferential selection on those families that have low levels of those hormonal products, you can reduce the incidence of boar taint in your herd by 25%.

It’s not about applying selection pressure, it is about sorting the animals once they reach maturity and breeding from the lines with low levels of androstenone and skatole.

There have also been proven differences in boar taint between breeds, for example, a Duroc breed is more at risk of incidences of boar-taint than a Pietrain. Research that has been conducted at one of our farms in Spain has also proven that by breeding two of PIC’s pigs – the Camborough gilt and the PIC 408 Pietrain – a lower incidence of boar taint can be attained than any other combination tested.

Gene-editing is another method that is progressing in its theoretical application to farming but is not deployed into the industry. To date animals have been reared that have been gene-edited to not reach sexual maturity, and therefore, this could reduce the incidence of androstenone and sketole in male pigs. This research has been applied to other issues in pig production, such as PRRS disease, but, so far, this is only experimental.

Can genetics solve everything?

Realistically, there are a lot more practical options than genetics to reduce the hormonal products that are known to cause boar taint – keeping your pigs clean can actually reduce your incidences of skatole in terms of carcass quality.

Changing nutrition has also been proven, through research published in the last year, to impact upon levels of boar taint. Formulating a diet specific to your breed and avoiding supplements that are now known to increase boar taint. For example, skatole and, in some cases androstenone, can be reduced by altering the tryptophan levels in swine diets.

When it comes to reducing boar taint on a practical level around Europe, there should be a multi-factorial approach taken. Genetics will play a part, but good nutrition and management can help with producing the best product.

At PIC, we understand that when it comes creating a pig that works in commercial industry, we need to be able to pull all of these disciplines together to make the best genetic improvement can, but to also be able to manage and feed the pig, whilst supporting the customers because we need to get the genetic potential out.

Craig R G Lewis PhD

Genetic Services Manager

PIC Europe

A native of Hereford, England, Craig Lewis is a member of the PIC Global Product Development team, based in Barcelona, overseeing Genetic Services for the European, Russian, and African region and is active in PIC’s global welfare research programme. Additionally, he is responsible for directly managing the genetic programme for a number of PIC’s key customers and internal multipliers. External to PIC, Craig is currently the chair of the steering committee for the European Forum of Farm Animal Breeders (EFFAB) which is a cross species European political lobby association that represents the majority of animal breeding and reproduction organisations within Europe.