Small-scale pig keeping: the fundamentals of farrowing

Next in Dr Michaela Giles's series of small-scale insights: a simple and easy-to-follow account of farrowing from triggering labour, to normal farrowing patterns, to complete aftercare.Part of Series:

< Previous Article in Series Next Article in Series >

Pregnancy

Sows are pregnant for three months, three weeks and three days (115 days; normal range 111 to 120 days) measured from the first day of mating (service). A sow expelling piglets before 109 days should be classed as an abortion, and any piglets born between 109 and 112 days as a premature farrowing. Variation in pregnancy length can be due to age, environmental conditions, specific breed, or time of the year. It’s recognised that gilts and pigs carrying larger litters tend to have a shorter pregnancy length.

During pregnancy, it is ideal to keep the sow in a familiar routine, including her normal feed ration, to minimise stress and increase the implant rate of the fertile eggs. The viable foetuses secrete the pregnancy maintenance hormone progesterone, informing the sow she is pregnant.

Newly-pregnant sows should not be mixed with new pigs without gentle introduction. She can remain in her existing group right through to farrowing, but the other pigs are likely to show a lot of interest and increase the chances of her piglets being squashed.

A week or two before her due date it is advisable to give the sow separate accommodation, which has been cleaned, disinfected and bedded down. Use shorter or chopped straw for bedding material because the newborn piglets are less likely to get caught up or bury themselves making them harder to see by the sow.

Just before moving to the sole use farrowing quarters (indoor or outdoor) is also a good time to de-worm the sow against parasites and administer any vaccination boosters about two to four weeks before farrowing to ensure the transfer of high protective antibody levels to the milk.

Farrowing trigger

The piglets are responsible for their birth date by secreting corticosteroids – in response to reducing nutrient availability - stimulating the placenta/uterus to produce the hormone prostaglandin. This directly causes the piglets to cease secreting the pregnancy maintenance hormone progesterone, initiating the birthing process. The normal farrowing process has a huge variation of birthing indicators and in the times taken, varying from sow to sow, and even between different litters from the same sow.

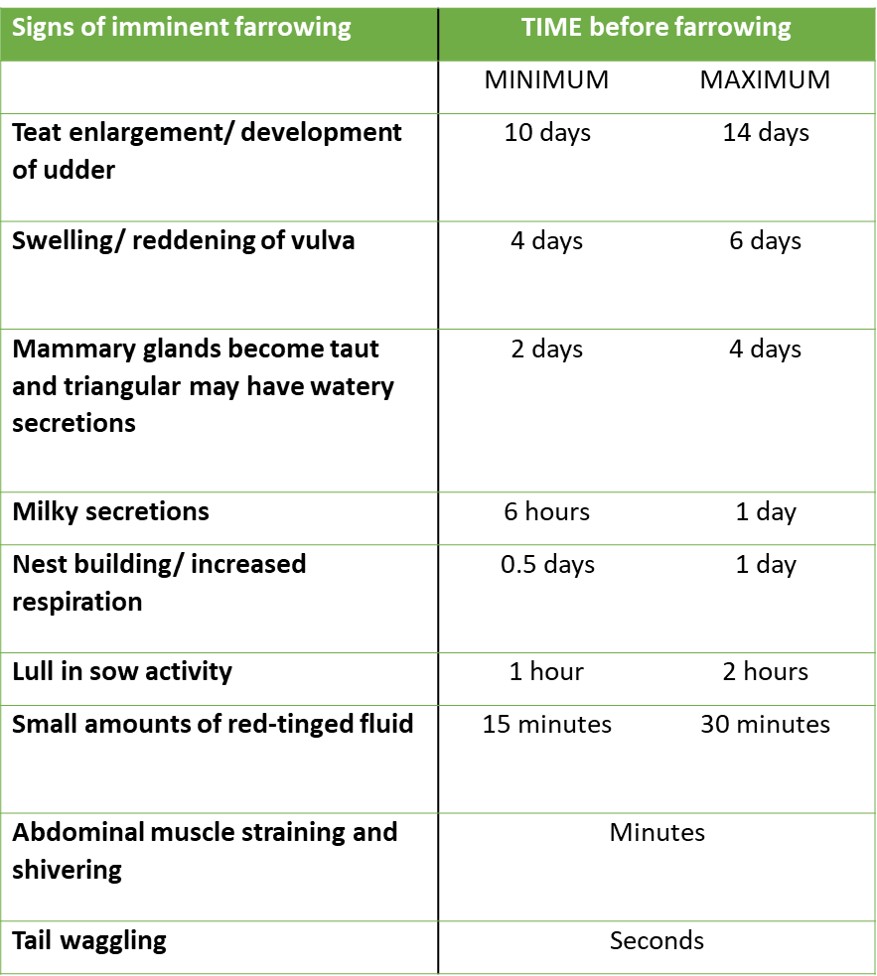

The preparation for farrowing gradually begins approximately two weeks prior to the actual date, with teat enlargement and the increase of prominent veins in the udder due to an augmented blood supply to the area. The vulva begins to swell and may redden around four days before farrowing. The mammary glands become taut, triangular and more defined about two days before farrowing. Watery secretions from the teats may be seen two days prior, which become more ‘milky’ within 12-24 hours. If milk is abundant and easily flows when the teats are gently squeezed, then the sow is probably within six hours of farrowing. Restlessness and nest-building are signs that the birth will be in the next eight to 24 hours, with sows weaving straw, grass, twigs and any other available material into the most impressive constructions. Their respiration rate may also increase as they prepare, peaking around nine to 10 hours before farrowing. Finally the cervix dilates, opening up the exit route.

© Tedfold Cottage Farm

Normal farrowing patterns

About an hour before giving birth, the sow’s activity may calm and she may lie quietly on her side in her nest before the straining begins, although every sow is different. Some sows can be increasingly agitated and restless, as the uterine contractions intensify. If they are very restless then a light sedative can be administered but only after consultation with a licensed veterinarian. Small amounts of red-tinged fluid may pass from the vulva, occasionally with pellets of meconium (faecal matter passed by the piglets before they are born).

An intermittent abdominal muscle straining occurs before the birth of the first piglet, usually accompanied by shivering, with the sow drawing her upper hind leg upwards. After the first-born, the straining usually becomes milder, except just before a piglet expulsion. Don’t be surprised if there is a 45 minute delay between the first and second piglet but from then on 10-20 minutes between live piglets is normal [range: minutes to a couple of hours] and a slightly longer delay between stillborn piglets of 35 minutes plus, but that does fall between documented normal ranges.

The majority of piglets are born head first with the front legs folded back (anterior presentation) but towards the end of farrowing there are more pigs presented backwards with the rear legs first and the front legs extended under the chin (posterior presentation). The twitching of the sow’s tail is a good sign that another piglet is due to arrive in the next 10 seconds. The whole birthing process takes between three and six hours (range: one to 10 hours).

The majority of piglets are born head first with the front legs folded back (anterior presentation). © Tedfold Cottage Farm

Newborn piglets are still attached to their umbilical cord and it breaks as they struggle and try to walk; if the sow does not object, you can spray the end of the cord with antiseptic or iodine, due to the length of the cord being a barrier to infection this is not necessary.

Newborn piglets are still attached to their umbilical cord and it breaks as they struggle and try to walk; if the sow does not object, you can spray the end of the cord with antiseptic or iodine, but due to the length of the cord being a barrier to infection this is not necessary. The umbilical cord is circa. 25 cm/11 inches and trails behind the piglet as it walks; the piglet can get caught up in it, but leave it alone, it shrivels rapidly.

Experienced sows are the least likely to get up and down during the birth; that behaviour is usually confined to first time gilts and, contrary to some books, the sows and gilts can deliver their piglets from both uterine horns without the need to get up or turn over. Sows may remain inactive for up to 95 percent of the first 24-48 hours.

The placenta/afterbirth is typically expelled within four hours after the last piglet (range: minutes to 12 hours). If you are present, within safe reach and know your sow well, check that there isn’t another piglet caught up in the afterbirth as occasionally it will be passed during the farrowing process. The afterbirth is commonly delivered in two halves one from each uterine horn, and sometimes whole at the end. A retained placenta is rare, and the failure to pass the afterbirth is often indicative that there is another piglet or piglets remaining in the birth canal.

Once the afterbirth has been passed, the sow should appear contented. She should be continually talking to her piglets, and the shivering and top hind leg movements will cease. There may be a slight to heavy discharge for up to five days; provided the udder is normal and the sow is eating well then it’s a natural post-farrowing process. If you have had to carry out an internal examination or assist in delivering piglets, give antibiotic cover to guard against infection.

Some sows will eat their afterbirth and any dead piglets and others won’t. Those not eaten must be disposed of in a licensed incinerator or by some other approved method and transported in a sealed and leak-proof container.

The placenta/afterbirth is typically expelled within four hours after the last piglet (range: minutes to 12 hours). If you are present, within safe reach and know your sow well, check that there isn’t another piglet caught up in the afterbirth as occasionally it will be passed during the farrowing process.

Attention and assistance

Signs of dystocia or “farrowing difficulty” include anorexia; prolonged pregnancy length; bloody or foul smelling discharge; piglet meconium passed without straining; prolonged labour; straining without piglets appearing; sow exhaustion and cessation of labour; and a distressed sow. The most common cause however is a piglet or two positioned incorrectly and blocking the birth canal.

Non-invasive assistance potentially required for:

- Rescuing piglets from within their placenta.

- Drying piglets off with paper towels to reduce chilling.

- Draining of fluids by gently swinging the piglet by its back legs if breathing is difficult.

- CPR: mouth-to-mouth assistance to breathe alternated with rubbing the chest. of the piglet.

There are two primary reasons for a sow to fail to deliver piglets:

- Inertia - a failure of the uterus to contract most often occurring part way through farrowing and is more likely to occur in older sows or sows/gilts in extreme body condition (either too fat or too thin). Intervention is required to avoid subsequent stillbirths.

- Obstruction. This can result from oversized piglets (particularly in gilts), malpresentation (eg, sideways), dual presentation (two attempting to exit simultaneously) and foetal abnormalities.

In such cases, the sow will strain excessively with expulsion of small amounts of fluid but no piglet. If straining continues unproductively for more than 15 minutes, manual examination is necessary. If this is your first time performing a manual examination, then every attempt to have a vet attending should be made.

If this is not possible then you need to be as clean and gentle as possible.

- Wash your hands/arms and the sows vulval lips with soap and water and rinse well.

- Wear a full arm-length glove*.

- Liberally use sterile lubricant*.

- Compress hand to a point and slowly insert in an upwards direction at an angle of 45 degrees until a piglet is felt.

- Grasp piglet by the legs or place finger in the piglet’s mouth supporting the lower jaw with your thumb. If possible, grasp the piglets head with your whole hand.

- Slowly withdraw the piglet.

- Once the whole litter is delivered and the sow is content, antibiotics must be administered.

*essential for breeders to have in their farrowing kit

If no obstruction is found, inertia is likely and if piglets cannot be reached (common in big sows), strategic use of oxytocin is appropriate strictly under veterinary direction as further complications can arise if overused.

Aftercare

Once farrowing is complete, the sow will stand, urinate and lie down to suckle the piglets to provide the vital colostrum. The piglets should fall asleep at the teats while the sow grunts to them softly.

Sows may not be interested in their food after giving birth for a short while, but their appetite should return within 24 hours. Keep a close eye on the sow for the first few days, as if she continues to be off her food and lethargic, she could lose her milk supply (agalactia) due to mastitis or metritis. If this happens, call your vet and/or administer antibiotics immediately. If all is well your sow should be fed to maintain her body condition score (BCS) of 3 to 3.5.

One problem that you hopefully won’t come across on your first farrowing is when a completely novice sow seems calm and controlled throughout the birthing process until one of the piglets moves up to her head, and then she becomes frightened by the ‘strange creature’ she can now see. She may even try to bite or kill the piglets when she gets up and sees them all around her. If you can collect the piglets safely, without having to sedate the sow, eg they are near the rear door of the ark, scoop them up and put them together under a heat lamp until she calms down. It is rarely a permanent problem. If she doesn’t calm down, your vet can prescribe a sedative giving the piglets a chance to feed and get stronger.

During the birthing process and the following 24-48 hours is when the sow is most likely to squash her piglets. When the sow stands up, the piglets congregate around her legs and can easily get trapped when she lies down again. The less overweight the sow is, the quicker she can get up when they squeal from underneath her. Keeping sows at BCS 3 for the birth has saved many piglets from death.

The use of a farrowing rail or pen can help minimise squashed piglets, especially if you hang a heat lamp over the piglet area, as they are out of the sow’s reach. Successful outdoor farrowing in pig arks, without the use of heat lamps, can be achieved in temperate climates certainly with traditional breeds. The use of short chopped straw as bedding for the first week is preferable as the piglets cannot get caught up or hide in it. The sow will keep the piglets warm in the ark and even lie across the doorway to prevent drafts. When the sow leaves the ark, the piglets form a pile to keep warm which makes them obvious to see when she returns and less likely to be trodden upon. Longer straw can be used as bedding once the piglets are older.

© The Commuter Pig Keeper