Rice is viable alternative to reduce poultry and swine production costs

Rice can replace corn in animal diets, with nutritional quality and lower feed costStudies by Embrapa Swine and Poultry have shown that, from a nutritional standpoint, rice can supplement or replace corn in animal diets. The conclusion can be great news for swine and poultry farmers who are dealing with high prices due to the rising appreciation of corn and soybeans. Meanwhile, the excess rice supply in the domestic market (a surplus of 600,000 to 800,000 tons in the 2020/2021 harvest) supports the viability of using the grain to lower the cost of swine and poultry feed, which currently account for about 70% to 80% of production costs in the two activities.

“Embrapa has already shown that husked rice (brown rice) is perfectly able to supplement or replace corn in animal diets from a nutritional point of view,” said Embrapa Swine and Poultry researcher Jorge Vitor Ludke.

Corn and soybeans have been influencing the performance of swine and poultry for the last three years, according to data from Embrapa's Swine and Poultry Intelligence Center (CIAS), which monitors the behavior of production costs in both sectors monthly. In order to better understand how this influence happens in practice, one can observe the price trajectory for bags of corn and soybeans.

According to the Center for Advanced Studies in Applied Economics (Cepea), the real average price of a 60-kilogram bag of corn increased from R$50.11 in April 2019 to R$97.15 in April 2021 - that is, a 93.9% increase. In the same period, the cost of the bag of soybeans grew 68.1% higher. This means that swine and poultry production costs have grown at almost the same rate in the last three years.

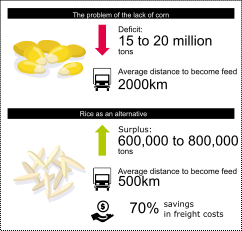

This upward movement in corn and soybean prices was driven by uncertainties related to the Covid-19 pandemic, appreciation of the dollar against the real, high demand for grains in the Asian markets (especially the Chinese one) and breaks in the first and second corn crop seasons due to climate problems and the corn spittlebug, according to a study by Brazil's National Confederation of Agriculture and Livestock (CNA) released in July 2021. The last estimate by the National Supply Company (Conab) is that the total corn production in the 2020/2021 crop year will reach 85 million, well below the initially projected 106 million tons. Therefore, it is expected that there will be a deficit of 15 to 20 million tons of corn in the domestic market in the short term.

Rice is on the other side of the spectrum. Rice farmers from Rio Grande do Sul and Santa Catarina, which are responsible for 91% of Brazilian production, reached record yield and delivered 8.5 million tons in the 2020/2021 harvest, the fourth largest in history. However, with the stabilization of consumption in the domestic market and less sales abroad (especially to Africa) than in 2020, there is leftover rice in the country.

“The priority use of rice is and will always be as human food. But now there is a surplus, and animal feed is an alternative," explains Rodrigo Ramos Rizzo, agricultural engineer and special advisor to the presidency of the Federation of Agriculture of Rio Grande do Sul (Farsul).

One sector's trouble is another's treasure

One sector's problem then became the chance to alleviate the other's situation. According to Rodrigo Rizzo, there are already sales contracts for rice in husks and broken rice between rice growers and chicken and pork farmers in Rio Grande do Sul state. However, the extent of the use of rice as an alternative feed will be defined by the price comparison with corn at the time of purchase. In October 2021, each kilo of corn for use in animal feed, on average, cost R$ 1.50, while rice reached R$ 1.82 (brown rice).

Thus the use of surplus rice to feed swine and poultry depends heavily on freight costs.

“That's why using rice as an alternative food source only pays off in places that can rely on major logistic advantages,” the researcher Jorge Ludke underscores.

That is the case of the Brazilian South. It is the region with the largest grain deficit for swine and poultry and also the one that concentrates the rice surplus. On average, a bag of rice travels 500 km in southern Brazil to be transformed into animal feed. In the case of corn, which comes mostly from Brazil's Midwest, the distance grows to about 2,000 km (from Sinop, MT, to Chapecó, SC), which entails a nearly 70% more expensive freight.

“The most important issue surrounding the use of rice at the moment is, in fact, to reinforce the debate on the creation of mechanisms to make the offer of alternative foods for animal feed permanent,” adds another researcher from Embrapa Swine and Poultry, Dirceu Talamini, an expert on issues related to swine and poultry production costs. The extent to which rice will help to reduce such costs, and the confidence that swine and poultry farming will thus consume the entire rice surplus are not clear yet. However, from late 2021 onwards, the three sectors certainly share concerns and work in synergy.

Rice is source of energy and good for carcass quality

When the idea to redirect the excess rice to feed swine and poultry was formed, Embrapa was called to assess the technical viability of such possibility. It was not the first time that this happened. In the early 2010s, for instance, there was a similar situation. At the time, Embrapa Swine and Poultry published Technical Communication 503, written by the researchers Everton Luis Krabbe, Teresinha Marisa Bertol and Helenice Mazzuco, which showed that rice offers not only nutritional value that suits swine and poultry diets, but also positive effects on carcass quality.

According to the technical document, “considering that rice oil presents a fatty acids profile in which there is a higher saturated and monounsaturated fatty acids content and lower polyunsaturated fatty acids content than corn, there is a tendency that a diet based on polished rice grains and soybean meal produces carcasses with a better fatty acids profile than a diet of corn and soybean meal, that is, with firmer fat”. However, the same document states that rice reduces the pigmentation of egg yolks and poultry skins, without losses in nutritional value for consumers. This issue can be solved by adding a pigmenting agent to the feed.

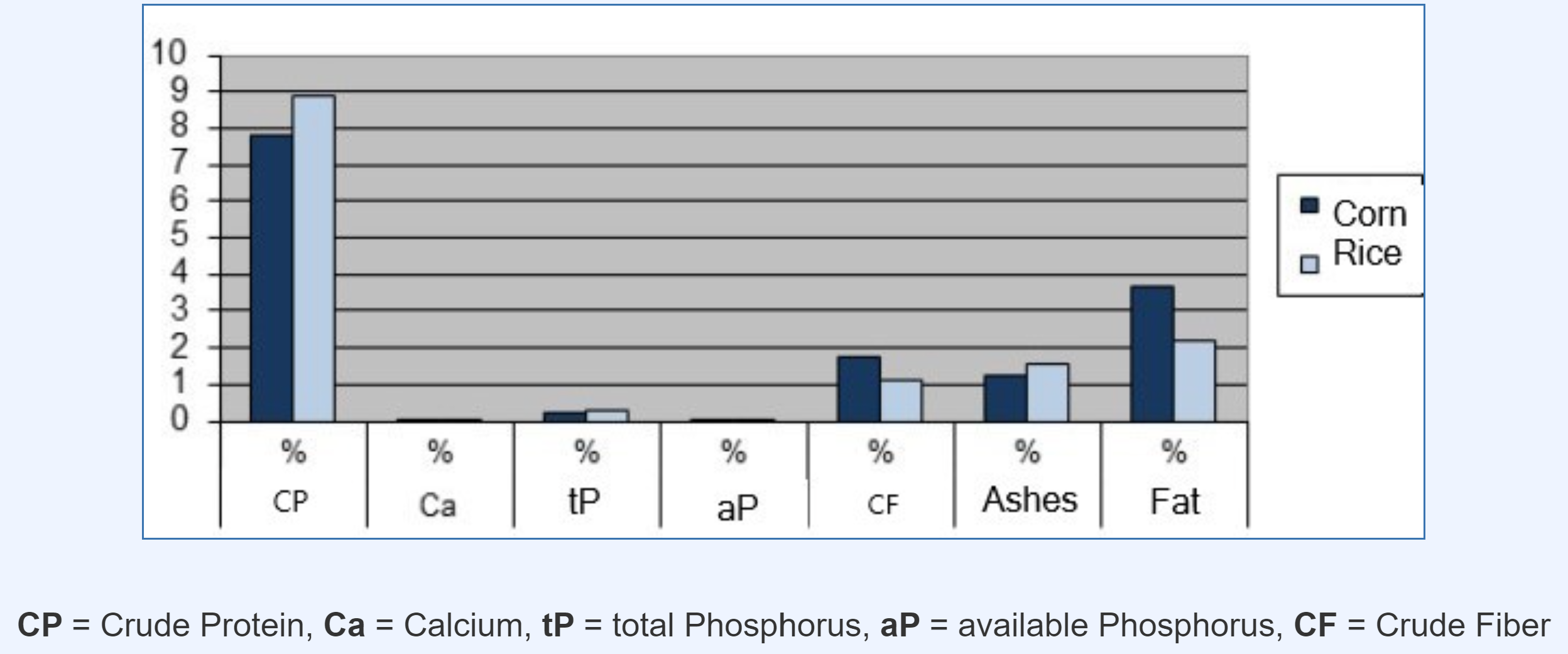

Embrapa's recommendations in the early 2010s are still valid (check the nutritional comparison between corn and rice in graph 1). The rice that is currently available to be used to feed swines and poultry is mostly brown rice. This type of rice has higher nutritional value than polished white rice and broken rice. However, brown rice needs to be husked. The husks have low nutritional value and contain a high fiber and silica content, which attacks the animals' intestinal lining and causes performance losses. All in all, “rice is a cereal whose crude protein level is very close to corn's, which makes it an excellent source of energy”, the researcher Jorge Ludke points out.

Comparison of the nutritional value of corn and of dehusked rice grains for poultry and swine

There are differences between dehusked brown rice, broken rice and polished rice from a nutritional standpoint. In the last two, the part that would constitute wholemeal rice bran is no longer present. Another important point is the fact that rice and corn have different shapes. Using rice to feed pigs takes specific adjustments in feed factories. “Milling needs to be adapted, with different sieve calibrations. But such adjustments do not represent significant costs or efforts”, Jorge Ludke adds. As for poultry feed production, no adjustments are needed. |

Use of rice is part of wider debate

The use of rice in animal feed is part of a recently resumed debate on how to ensure a continuous flow of alternative food sources for swine and poultry farming. Embrapa has been one the protagonists in such discussion, especially concerning the Brazilian South, where the deficit of grains for swine and poultry grows every year.

“We have contributed in this discussion with our research that shows how winter cereals can take up idle areas in the South and generate good results for grain and animal protein producers,” said researcher Teresinha Bertol, from Embrapa Swine and Poultry.