Researchers find new solutions to control mites in dry-cured ham

Methods could replace methyl bromideWith funding from USDA’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Mississippi State University and Kansas State University researchers have developed many safe and cost-effective methods and technologies over the last 15 years for the dry-cured pork (country ham) industry to control pest infestations.

Specifically, they have targeted mites and various insect pests. And by employing environmentally friendly methods, researchers have designed potential replacements to the pesticide methyl bromide, an ozone-depleting gas.

“Through the Methyl Bromide Transition Program (MBT), NIFA works to address the immediate needs and the costs of transition that have resulted from the phase-out of methyl bromide,” said Dr. Amer Fayad, National Program Leader who oversees the NIFA grant program. “Methyl bromide had been a pest and disease control tactic critical to pest management systems for decades for soilborne and postharvest pests.”

Importance of the dry-cured ham industry

There are approximately 3 million dry-cured hams produced in the United States each year. This research contributes to the sustainability of the industry by enabling dry-cured ham producers to be able to make hams that are aged for 6, 12 and 24 months as well as boost production of these valuable commodities. The 12- and 24-month aged products often sell for $200 to $300 per ham due to their aged flavor and texture. They are included in dishes in high-end restaurants in major cities.

“We are addressing the difficulty in producing artisan dry-cured meat products without mite infestations,” said researcher Wes Schilling with Mississippi State University, who co-led the study with Tom Phillips at Kansas State University. “After approximately five months of aging, hams and other meat products are susceptible to mite infestations. This is because the moisture, protein, fat content and characteristic flavors of long-aged meat products make them a desirable food source for mites. Since mites are everywhere, they can get on these hams even though they may have excellent sanitation, pristine processing and new facilities.”

New methods developed

The methods researchers developed include, but are not limited to, alternative fumigants, controlled atmosphere, food grade ingredients, sanitation, physical barriers and detecting and monitoring the pests for decisions in integrated pest management programs. They also are focused on interacting with dry-cured pork producers to scale up technologies and practices in ham plants to control mites.

Mites are very tiny, abundant in many structures, and difficult to find due to their huge reproductive abilities under ideal conditions of food and warmth, Phillips explained. However, researchers know mites can be kept at low levels with proper prevention and effective mitigation when needed.

“Nothing works as well as methyl bromide fumigation to control mites, so sanitation, inspections for mites, food-grade coatings, fumigation and best practices need to be implemented when an infestation threshold is reached,” Schilling said.

Training the next generation of researchers

Not only is this research helping sustain the dry-cured ham industry, but it is also contributing to the development of the next generation of agriculturalists and researchers who will work to address commodities with critical issues. Work force development is a NIFA priority.

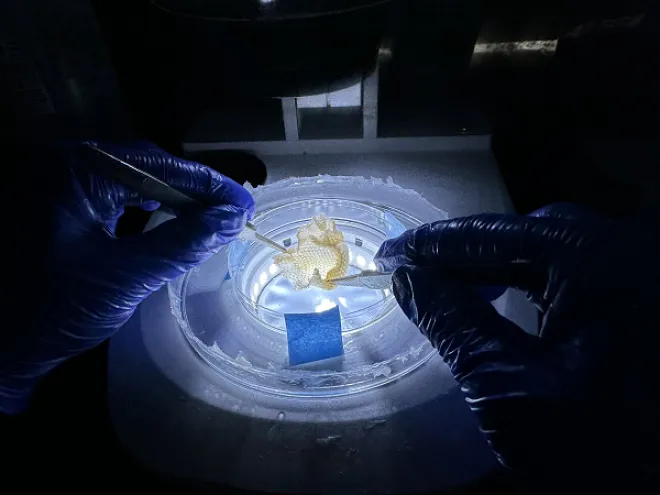

Xue Zhang focused on finding effective and safe ways to control ham mites using food-grade materials in coated nets while earning her Ph.D. at Mississippi State. Now, as a Co-PI and assistant research professor at Mississippi State, she is actively involved in the team, exploring more novel, cost-effective and safe strategies to manage ham mites.

“What captivates me about this research is its integration of various fields like food science, biology, and regulatory processes,” Zhang said. “It’s not just theoretical; it’s about solving real issues in the dry-cured pork industry and making a tangible impact on how things are done.”

Being part of the NIFA-funded project during her Ph.D. significantly improved her academic skills, she said. The hands-on experience provided practical insights, fostered critical thinking and refined her writing abilities. As her career has progressed, the project equipped her to write grant proposals and mentor both graduate and undergraduate students.

“My ultimate career goal is to use my knowledge and the latest technologies to ensure the production of safe and high-quality foods,” Zhang said. “This research aligns perfectly with that goal, providing skills and knowledge directly relevant to my desired career path in the food science field.”

Like Zhang, Mississippi State University graduate student Sawyer Wyatt Smith has enjoyed working on the project because he is making a direct impact on not only one sector, but the entire food industry.

“We have successfully discovered various potential alternatives to replace methyl bromide in the dry-cured meat industry and plan to upscale and improve manufacturing processes to deliver these products to the market. All these items come together to make possibly the greatest lesson a student can learn from and take with them throughout their career,” he said.

Being involved with a NIFA-funded program has fostered his professional growth as a scientist and researcher. He explained that developing alternatives for a sustainable future requires creativity, scientifically sound experimental designs and conduct, succinct reporting, outreach, service and direct industry involvement. The research also inspired him to found his own business, Diversified Food Solutions LLC. His career goal is to become a professor of food science or related agricultural discipline.