Pork remains the favourite in the Philippines

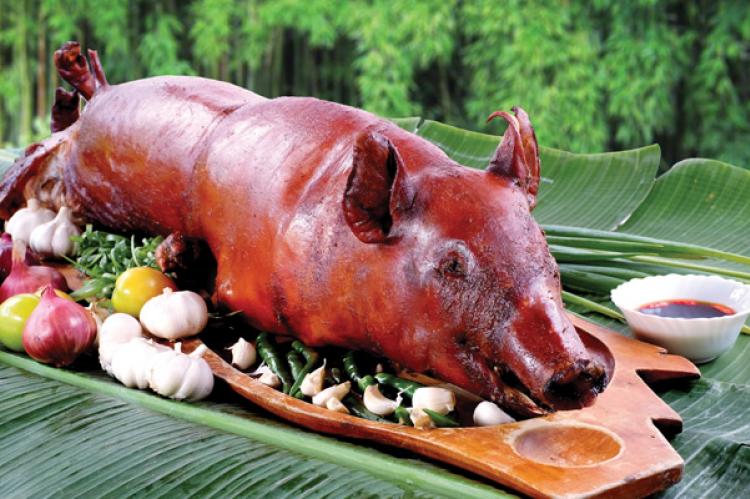

Gregg Yan explores how population growth, global demand and disease outbreaks are changing the pork market in the Philippines.Pinoys absolutely love pork. Randomly enter a restaurant and there’s a fat chance you’ll sniff the rousing aroma of sizzling sisig, grilled liempo or if your host is big-time, lechon – a whole roasted pig!

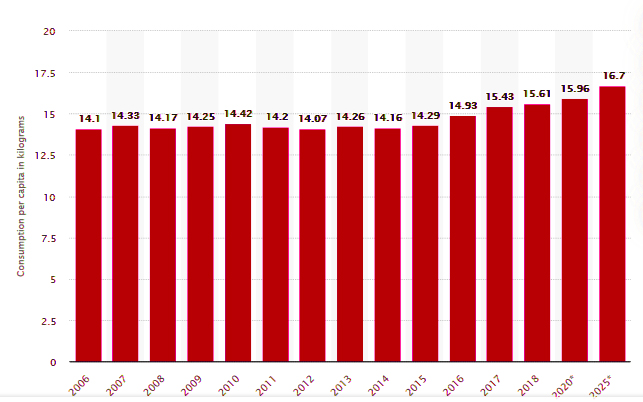

The Philippines is the world’s tenth-largest consumer, eighth-top producer and seventh-largest importer of pork. Pinoys love to pig-out, gobbling up about 35 kilogrammes of meat yearly, including an average of 15 kilogrammes of pork.

It’s no surprise that the local swine industry is one of its most lucrative trades, worth PHP200 billion or USD5 billion and contributing 18.28 percent to the country’s agricultural output in 2015, ranking second only to rice and staying way ahead of poultry.

Native hogs are said to have the best flavour, giving free-range farmers many opportunities to expand both locally and globally. © Mila's, 2019

Meat for the masses

With a capital city hosting 13 million and a national population of 101 million excitable, food-loving citizens, the Philippines is hog-heaven because pork is an interim meat between always-pricey beef and occasionally-cheap chicken. The industry is growing steadily as the country’s population expands at an average rate of 1.6 percent yearly, meaning there are nearly 5000 new mouths to feed every day.

As of January 2019, the Philippines recorded 12.71 million head of pigs, 0.83 percent higher than the 12.60 million listed in 2018. The majority – about 63 percent – are farmed by small-scale operators in backyard piggeries with less than 100 hogs. This provides tens of thousands of lower and middle-class Pinoys good business and livelihood opportunities, as the piglets can be tended by children or unemployed family members to grow upwards of 100 kilogrammes in just six months.

© Statista, 2019

“Many households invested their savings by buying pigs, which can be fed the family’s scraps, converting uneaten food to minimise food waste,” says Roy Alimoane. “Money grows when you invest in pigs. This might be a reason why we still put our money in piggy banks.”

Commercial ventures make up about 37 percent of production and include sprawling state-of-the-art operations like Sunjin, Family Farms and Pig City. By 2016, the country was producing 1.2 million tonnes of pork yearly.

Because of consistently rising demand however, the Philippines has also become a major pork importer, shipping in 312,499 metric tonnes of pork from Europe and other regions in 2018, a 13.85 percent jump from 2017, as reported by the Philippine Statistics Authority.

To reduce importation, close the gap and become self-sufficient, local production efficiency should be improved. The industry is ripe for research and development in better feeds, breeding and rearing techniques, plus automation.

Digitised and AI-assisted operations can greatly improve yields and reduce losses from disease, while ethical and sustainable waste management will help minimise environmental impacts (and complaints about smelly environs). Local sow productivity is also set to improve, with the Department of Science and Technology (DOST) working on ways to boost sow productivity by at least four piglets yearly – a 30 percent production boost without increasing sow numbers.

Aside from intensive-rearing of popular breeds such as the Large White, Landrace, Duroc and Piétrain, more farmers are trying out pastured and organic rearing of native pigs, which are healthier and lower in cholesterol than hogs raised in piggeries. Some farms are also dabbling with newer breeds and free-range techniques, such as Sitio Anting, recently featured by The Pig Site.

Good export opportunities can be maximised if the country offers unique products, such as native lechon or roasted native Philippine pig. However, the industry faces some hefty challenges.

© Gregg Yan

Containing African swine fever

Undoubtedly the biggest setback for the Philippine swine industry is the recent global outbreak of African swine fever (ASF), which is suspected to have been brought into the country via contaminated food scraps as early as July 2019.

ASF is a deadly and highly-contagious virus which affects both farmed and wild pigs. It can be spread through live or dead hogs, plus anything which has come in contact with tainted meat – knives, wastewater and even undisinfected worker’s hands.

Once an animal contracts ASF, it has little chance of surviving coupled with a huge chance of spreading the virus to other animals. Affected animals are thus usually destroyed to prevent undue suffering and to contain the spread of disease. To date, there is no approved ASF vaccine.

The Philippine Department of Agriculture (DA) and Bureau of Animal Industry (BAI) are attempting to stamp out the virus through improved biosecurity, quarantine, area-wide bans and preventive culling.

The United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO)estimates that as many as 136,000 pigs have been affected in the Philippines. Around 70,000 have been destroyed and import bans have been implemented for pigs sourced from a dozen countries including Germany, China, Russia and Vietnam, where nearly six million pigs have been culled. Many Pinoy farms have sold off their entire herds at all-time low prices, driving the price of other meats up. Tens of thousands of workers employed by the meat processing and packing industries have lost their jobs.

The Philippine government has been compensating farmers who have willingly culled their pigs by providing PHP5000 or USD100 per head, compared to the hogs’ market value of at least PHP10,000 or USD200.

As is clearly evident, ASF’s industry impacts over the past five months is significant – the industry is losing around PHP1 billion or USD20 million every month.

In order to stay competitive, hog raisers need to be extra-vigilant in policing and protecting their herds – not just against ASF, but against other diseases like Classical swine fever (hog cholera), Pseudorabies and Circovirus. Research on environmental changes such as climate change should also be prioritised to ensure that these plucky porkers bounce back and continue to hog the top livestock spot for the Philippines.