Parasite Control in Youth Market Hog Projects

Advice on the control of external and internal parasites aimed at show pigs from Dr Susan Kerr, DVM, Livestock and Dairy Extension Specialist with Washington State University for Pork Information Gateway.No "one size fits all" recommendations can be made regarding parasite management of youth market hog project animals. Variables such as deworming treatments and other care given before purchase of the project animal, quality of the animal’s feeding program, sanitation, length of the project, environment, health status, and genetic factors may also influence performance.

Sanitation is Essential

Sanitation plays a big role in determining the types and numbers of parasites that affect pigs. Prompt removal of faeces from the pig’s environment will lessen the chances of a pig re-infesting itself with parasites. Housing pigs on solid surfaces such as concrete with bedded areas will allow for frequent cleaning and disinfection of soiled areas. Letting pigs roam on dirt and root is good for their feet, legs, and general wellbeing, but it is important to understand this management practice will likely increase their exposure to parasites.

Intestinal Parasite Life Cycle Example

A review of the swine roundworm’s (Ascaris suum) life cycle may help youth producers understand the crucial role that environment can play in an intestinal parasite’s life cycle.

As shown in Figure 1, adult roundworms in a pig’s intestine produce eggs, which are released in the pig’s faeces (A). These eggs mature a little in the environment (B, C); sometimes they are ingested by earthworms (D).

Pigs become infested and re-infested when they ingest dirty feed, water, manure, soil, or earthworms that contain these eggs (E).

After being swallowed, immature roundworms move from the intestines (F) to the liver (G) and lungs (H), causing damage all along the way.

In the final steps of the roundworm life cycle, the pig coughs up the immature parasite from its lungs then swallows it (I), so the parasite finally matures into an adult within the pig’s intestines. The cycle begins again when the parasite produces eggs.

To Deworm or Not to Deworm?

If a project pig was dewormed early in life and is fed an excellent diet and kept in sanitary conditions, perhaps it may not require more deworming before going to market. However, this can only be determined through a faecal analysis for parasites. This procedure can be performed at a veterinary clinic or by producers who have learned how to do it.

Many project pigs are owned and managed for about three months, so perhaps just one treatment may be needed; it will depend on the animal’s exposure to parasites, appearance, general health, and performance (rate of gain). faecal analysis can reveal the types and severity of parasite infestation, which, in turn, will influence the decision about which, if any, deworming medication should be used.

External Parasites

External parasites of swine include lice, ticks, mites and flies. These parasites can cause pigs to scratch and damage their skin. They also induce stress, reduce feed intake and slow weight gain.

Ivermectin-type products will kill ticks, mites and some types of lice; other lice must be killed with chemicals applied to the pig’s skin – check with your veterinarian for more information.

Good sanitation will help minimise fly populations. Other management options to control flies include predator wasps and chemicals approved for use in livestock environments.

Follow all label instructions carefully and use personal protection equipment to prevent human exposure.

Internal Parasites

Internal parasites are a constant challenge to keeping pigs healthy and growing well. They are of special concern in young and pastured animals.

Different internal parasites can live in the intestinal, respiratory, muscular and urinary systems, so the signs of illness will relate to the affected tissues.

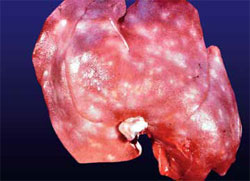

Signs of internal parasitism can include diarrhoea, constipation, colic, poor appetite, hiccoughs ("thumps"), poor growth, anemia, weakness, difficulty breathing and even death. In market animals, parasites are a quality assurance issue as well, reducing rate of gain and causing valuable products to be discarded (Figure 2).

Treatment

Fortunately, most swine medications work against multiple parasites and are considered safe and easy to administer. Most are fairly cost-effective as well. Check with other 4-H youth who have market hog projects in your area and share the cost of an effective product because most products will expire before a small-scale producer can use up an entire container. See Table 1 for a summary of medications appropriate for use against the most common internal parasites of swine. However, be aware that medication availability can change at any time.

Parasite resistance to specific medications may develop on individual farms due to underdosing, overuse or other management errors. For example, even though piperazine is labeled as effective against the nodular worm, on many farms it may be completely ineffective against this specific parasite.

Read medication labels to check for claims about effectiveness against specific parasites and follow all label instructions carefully. Follow all withdrawal times when using medication to be sure the appropriate amount of time has passed before marketing your animal for human consumption. Several swine parasites can be transmitted to humans, so be sure to wash your hands well after handling pigs and other livestock. In addition, always cook fresh ground pork to an internal temperature of 160°F and fresh pork cuts to 145°F.

Valid Veterinarian-Client-Patient Relationship is Essential

As long as you use over-the-counter swine deworming products exactly as instructed on the label and follow all meat withholding guidelines, you are following all US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requirements and are staying within federal law. However, if you use a product not approved for use in pigs or if you use a product approved for use in pigs in a manner other than exactly as instructed on the product label, you are violating federal law and are subject to fines and even prosecution.

If your veterinarian determines it is necessary for your pig’s health that you give your animal a non-approved product or a different dose of an approved product, it is legal as long as you have a valid veterinarian-client-patient relationship and you follow the veterinarian’s recommendations exactly.

Your veterinarian will give you guidance on how long to keep your animal before selling it to market channels. You must record and keep all this information (injection site, dose, date, medication name and lot number, animal identification, etc.) to document this legal extra-label use of a medication.

Aspects of a Veterinarian-Client- Patient Relationship (VCPR) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||

| Adapted from information at www.avma.org. | |||||||

Table 1. Summary of common intestinal parasites of swine and approved medications.1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parasite | Common name | Location | Approved medications | Notes |

| Trichuris suis | Whipworm | Large intestine | Fenbendazole, Dichlorvos, Hygromycin B | May cause bloody diarrhoea and stunting. Eggs very hardy in environment. |

| Oesophagostomum dentatum | Nodular worm | Large intestine | Pyrantel, Piperazine, Levamisole, Fenbendazole, Ivermectin, Doramectin, Dichlorvos, Hygromycin B | Eggs very hardy in environment. |

| Strongyloides ransomi | Threadworm | Small intestine | Levamisole, Ivermectin, Doramectin, Thiabendazole | Big concern in young piglets. Larvae can be ingested in feed, water, or sow’s milk, and can penetrate skin. Sanitation important. |

| Metastrongylus spp. | Lungworm | Lung | Levamisole, Fenbendazole, Ivermectin, Doramectin | Eggs coughed up, swallowed, and passed in manure. Earthworms are required part of life cycle, so outdoor pigs are at risk. |

| Stephanurus dentatus | Kidney worm | Kidney | Fenbendazole, Doramectin, Ivermectin, Levamisole | Lives in and around kidney; damages liver and muscle too. Larvae are in environment and can contaminate feed, penetrate skin, and be consumed in infected earthworms. |

| Ascaris suum | Ascarid or large roundworm | Small intestine | Ivermectin, Fenbendazole, Levamisole, Pyrantel, Dichlorvos, Piperazine, Thiabendazole, Hygromycin B, Doramectin | Common in young pigs. Eggs very hardy in environment. Larvae migrate through liver and lungs. |

| Hyostrongylus rubidus | Red stomach worm | Stomach | Fenbendazole, Ivermectin, Doramectin | Cause stomach inflammation and anemia. Good sanitation stops re-infestations. |

| Ascarops strongylina | Thick stomach worm | Stomach | Dichlorvos, Ivermectin | Life cycle involves beetles, which pig must consume to become contaminated. Good sanitation prevents re-infestation. |

| Macracanthorhynchus hirudinaceus | Giant thorny-headed or spiny-headed worm | Small intestine | No approved medications, although some are effective. Get approval from veterinarian for use. | Life cycle involves beetles, which pig must consume to become contaminated. Good sanitation prevents re-infestation. |

| Trichinella spiralis2 | Trichinosis worm | Small intestine and muscles | No treatment necessary in pigs. | Humans can contract disease by eating undercooked meat. Prevention: boil food wastes fed to pigs for 30 minutes. |

| Taenia solium2 | Tapeworm | Muscles | No treatment necessary in pigs. | Prevent infecting humans by properly cooking pork and preventing swine contact with human waste. |

| Eimeria and Isospora spp. | Coccidia | Small intestine | No approved medications. | Eggs hardy in environment. Control through good sanitation and waste management. |

| 1 Note: Some medications come in more than one form (for example, feed pre-mix and injectable), and not all forms of a medication may be effective against the same parasites. Confirm by reading the label before treatment. Some forms are available over-the-counter and others by veterinary prescription. 2 Transmissible to humans. |

||||

Conclusions

The health status of your market hog project is a very important factor affecting the production of a high quality food product.

Market hogs kept in environments with excellent sanitation may need minimal treatment for parasites during the market hog project period. Parasite control should not rely only on medication; overuse of deworming medication can cause parasite resistance to develop.

Some immunity to parasites develops as pigs mature, so most parasite concerns are focused on young pigs.

Reduce the risk of parasite infection of your market hog by maintaining a clean environment, providing a balanced diet, minimising stress and housing pigs together according to age.

Disclaimer

The information herein is supplied for educational or reference purposes only, and with the understanding that no discrimination is intended. Listing of commercial products implies no endorsement by WSU Extension. Criticism of products or equipment not listed is neither implied nor intended. Changes in medication availability may invalidate the information in this publication.

Further Reading

Aiello, S.E. and M.A. Moses, eds. 2012. The Merck Veterinary Manual Online. Whitehouse Station, New Jersey: Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. www.merckvetmanual.com.

Compendium of Veterinary Products. 2010. 12th ed. Port Huron, Michigan: North American Compendiums, Inc.

Corwin, R.M and R.C. Tubbs. 1993. Common Internal Parasites of Swine. University of Missouri Extension Publication G2430. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri. http://extension.missouri.edu/publications/DisplayPub.aspx?P=G2430.

Foreyt, W.J. 2001. Veterinary Parasitology: Reference Manual. 5th ed. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell.

Moyer R.O. and J.H Brendemuhl. 2003. Controlling Internal Parasites in Swine. University of Florida IFAS Extension Publication AS50. Gainesville, Florida: University of Florida IFAS Extension. http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/an039.

Muirhead, M. and T. Alexander. 2012. Pig Health Index. Chicago: 5m Enterprises, Inc. www.thepigsite.com/pighealth.

United States Food and Drug Administration. 2013. Approved Animal Drug Products Online (Green Book). www.fda.gov/AnimalVeterinary/Products/ApprovedAnimalDrugProducts/default.htm.

September 2014