Larger litters and more competition for colostrum make pigs more susceptible to clostridial enteritis

Clostridium perfringens is one of those pathogens that’s almost always a threat to sow herds and their neonates.It’s no wonder because clostridium is ubiquitous. It’s found in the intestinal tract of pigs, in sow faeces and the environment, including soil. It can be tracked around on boots and other fomites.

In suckling pigs, C. perfringens remains a primary cause of enteritis. In one study involving more than 500 scouring pigs, investigators isolated this bacterium from nearly 90 percent of the pigs in a large integrated production system and from more than 95 percent of pigs on 16 smaller farms in eight states.1 The study, conducted in the Midwest, demonstrates just how common C. perfringens can be on swine-production sites.

Piglets become infected with C. perfringens orally, from sow faeces, usually during the first days of life. Pigs may be more susceptible to enteritis if they have inadequate colostrum intake2 - a growing concern as litter size continues to increase.

Type A versus C

In that Midwestern study, the large majority of C. perfringens isolated was type A, which can lead to mortality but more often causes a milder enteritis compared to the more virulent C. perfringens type C. Pigs with type A have diarrhoea, but it’s generally pasty and not profusely bloody. Their haircoats may be roughened. Infected pigs may recover, but stunted growth is a good possibility.3

The clinical signs of C. perfringens type A are similar to other pathogens that can cause diarrhoea, so a careful diagnosis is needed. Polymerase chain reaction technology is helpful in this regard.

The picture is very different when enteritis is caused by C. perfringens type C, which has a variable incidence and is high in some areas of the US.4 Pork producers unfortunate enough to have herds affected by this version of the pathogen know the signs. Young piglets have offensive-smelling diarrhoea that’s often bloody, and many die suddenly.

Mortality from C. perfringens type C can be as high as 100 percent in weak litters and can occur in just a few hours, even before the characteristic diarrhoea is seen. Another sign may be blackened abdominal skin.5 The typical pattern is acute disease, but sometimes we see chronic versions that sicken pigs and lasts the entire nursing period.

A presumptive diagnosis of C. perfringens type C can generally be made based on the clinical picture and the presence of large, Gram-positive, rod-shaped bacteria in Gram-stained mucosal smears. Necropsy will, of course, confirm diagnosis of the disease, which tends to recur on infected farms.6

Treatment of clostridial enteritis may be futile because the infection is usually advanced by the time clinical signs show up, underscoring the importance of control.

Management options

Vaccination of pregnant sows might provide some protection for subsequent litters if the piglets consume colostrum soon after birth.7 This approach should be discussed with the herd veterinarian. It may be one of the few options for producers raising herds without antibiotics.

For producers with conventional herds, another strategy is administration of BMD® (bacitracin methylene disalicylate) to sows. Because FDA does not consider the antimicrobial medically important to humans, it may be used without a veterinary feed directive. However, we still advise consulting with a veterinarian on all matters related to disease management.

The feed additive is indicated for control of clostridial enteritis caused by C. perfringens in suckling piglets when fed to sows from 14 days before through 21 days after farrowing on premises with a history of clostridial scours. We’re aware that some cost-conscious producers have experimented with eliminating the 14-day prefarrowing treatment and feeding the medication to sows during lactation only. Studies we’ve conducted with the help of large swine integrators indicate producers may be short-changing themselves with this approach.

While feeding BMD only during lactation may reduce the impact of C. perfringens on piglets compared to pigs from unmedicated sow controls, the payoff is greater when BMD is administered to sows for the full 5 weeks as indicated.

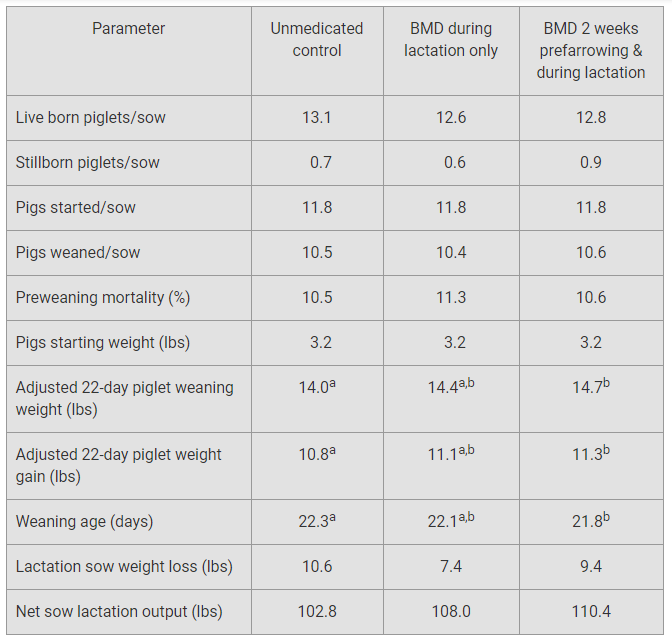

This was demonstrated in a study involving nearly 200 litters per treatment.8 We compared results among a control group of sows not medicated with BMD, a group of sows that received BMD only during lactation and a group that received BMD before farrowing for 2 weeks and throughout lactation for a total of 5 weeks. BMD was fed at the rate of 250 grams per ton of feed.

Pigs from sows treated for the full 5 weeks had greater adjusted 22-day weaning weights and greater adjusted 22-day weight gains compared to pigs from control sows (Table 1). The adjusted 22-day weaning weight and adjusted 22-day weight gains of pigs nursing sows on the 5-week programme were numerically greater than pigs nursing sows consuming BMD in lactation only.

Sow weight loss in lactation was not different among treatments. However, the calculated adjusted 22-day litter weight gain was better for litters nursing sows consuming BMD. Therefore, the parameter “net sow lactation output” was numerically improved for sows consuming BMD.

This parameter is a measure of net sow lactation output; it’s calculated by subtracting sow weight loss during lactation from the 22-day adjusted litter weight gain. Sows consuming BMD for the 5-week programme had a substantially shorter lactation period (-0.5 days), yet they produced 7.5 more pounds of net lactation output than control sows.

em>a,b Different superscripts represent statistical significance (p < 0.05)

Reduced faecal-culture score

One of the major advantages of using BMD for the full five weeks is the impact on clostridial shedding by sows. This was demonstrated in another study with 106 sows. Sows received BMD at 250 grams per tonne only during lactation or they weren’t medicated and served as controls.9

In that study, C. perfringens type A was identified in the faeces of every sow in both groups at the onset of farrowing. However, at weaning, more than 44 percent of sows consuming BMD tested negative, whereas 100 percent of untreated sows were still positive.

It stands to reason that sows treated with BMD before farrowing will shed less clostridia in the farrowing crate than sows that aren’t treated prior to farrowing. Reduced shedding of C. perfringens is important because the clinical signs of clostridial enteritis can vary depending on the dose ingested by piglets10 - the more they ingest, the sicker they may be.

The improvement in results with the full, 5-week use of BMD before and after farrowing substantiates the findings of several other studies conducted over the years.11 The reduction in pre-weaning mortality, increased number of pigs weaned and better weight among pigs from treated sows can generate more income from each litter. It can provide a good return on investment12 and benefit animal welfare by sparing piglets from a disease that obviously causes substantial misery.

It should go without saying that prevention and control of clostridial enteritis shouldn’t depend on vaccination or in-feed treatment alone. Considering that enteritis is spread by contact with maternal faeces and can be tracked around by people and other fomites, it’s important to maintain high standards of farm biosecurity and piglet care.

| References | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Baker A, et al. | ||||

| (2010) | Prevalence and diversity of toxigenic Clostridium perfringens and Clostridium difficile among swine herds in the Midwest.. Appl Environ Microbiol. | May;76(9):2961-2967. | ||

| 2 Reese D, et al. | ||||

| (2015) | Baby Pig Management — Birth to Weaning. | Extension.org. | ||

| 3 | ||||

| Clostridial disease in pigs | Farmhealthonline.com | [accessed 20.09.2017] | ||

| 4 | ||||

| Clostridial diarrhea, | Iowa State University | [accessed 18.07.2019] | ||

| 5 Ibid. | ||||

| 6 Harris DL. | ||||

| Clostridium perfringens Type C enteritis in pigs. | Merck Veterinary Manual. | |||

| 7 Ibid. | ||||

| 8 Nelson D, et al. | ||||

| (2010) | The 5-week BMD sow feeding program yields heavier pigs than feeding BMD to sows only during lactation. | Am Assoc of Swine Vet annual meeting. | ||

| 9 Ibid. | ||||

| 10 | ||||

| Clostridial diarrhea, | Iowa State University. | |||

| 11 Wolff T. | ||||

| (2005) | An overview of research on bacitracin methylene disalicylate (BMD) in sow diets.. Proceedings Am Assoc of Swine Vet, | 101-105. | ||

| 12 Nelson D, et al. | ||||

| The 5-week BMD sow feeding program yields heavier pigs. |