Japanese encephalitis virus: Australian outbreak on pig farms

In the space of just one month, Japanese encephalitis virus went from being practically non-existent in Australia to infecting 50 pig farms across the eastern seaboard and the south of the country.Part of Series:

Next Article in Series >

Editor's note: The following are excerpts of a webinar presented by the Swine Health Information Center in collaboration with the American Association of Swine Veterinarians, as part of its mission to address emerging diseases.

Dr. Kirsty Richards is a veterinarian with a SunPork Group, Australia's largest pig farming integrator with 47 pig farms across Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia.

“On Saturday, the 26th of February, one of our Queensland farms was diagnosed with Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV), followed by one of our New South Wales farms on the 27th of February, one of our Victoria farms just under a week later on the fifth of March, and on the 22nd of March at a farm in South Australia and a second farm in Queensland,” she said. “These farms are entirely unrelated to each other and are spread over 1,500 kilometers (930 miles) in terms of distance from each other.”

By the end of March just over one month since the outbreak started, there were more than 50 infected farms across the eastern seaboard states of Australia and into the south of the country.

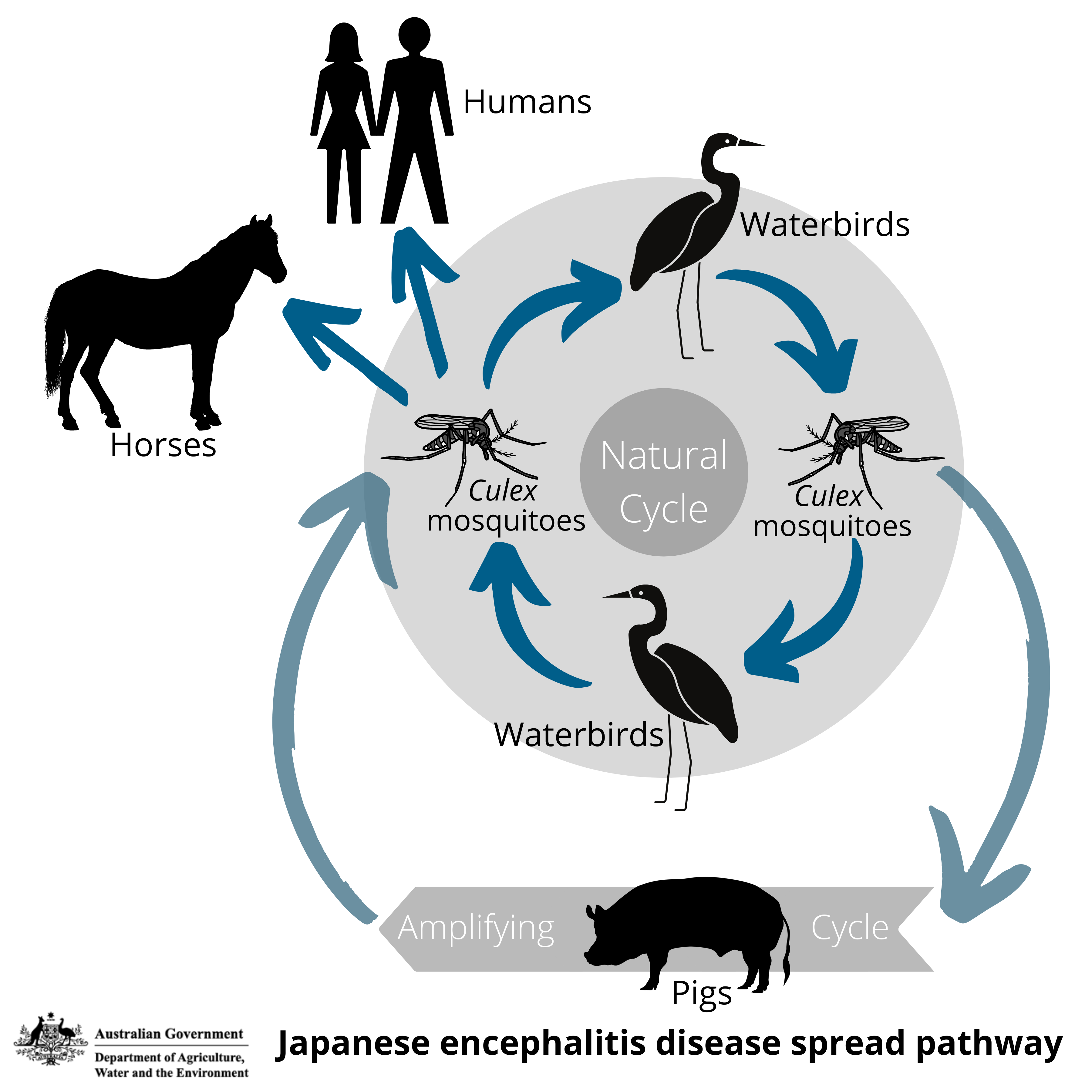

JEV is an arthropod borne virus in the flavivirus family, which is spread by the Culex annuallirostris mosquito. JEV has a sylvatic cycle with native waterbirds which include herons, egrets and bitterns.

Infection of humans, horses and pigs are a spillover event, not part of the natural viral life cycle of JEV, Richards noted. Humans and horses do not generate sufficient viremia to infect new mosquitoes, and hence are dead-end hosts.

“Pigs, however, generate sufficient viral load to reinfect mosquitoes and are thus an amplifying host,” she added.

While JEV is considered endemic in many parts of Asia, it was only a known risk in the far northern tip of the state of Queensland, she said.

“In the space of just over a week, we went from that little northern tip of Queensland to multiple pig farms across multiple states of Australia involved,” she said. All these outbreaks are genotype 4 JEV, Richards added.

Reproductive losses in pigs

Dr. Bernie Gleason is a veterinarian at SunPork Farms who witnessed the effects of JEV on sow herds. In January 2022, there were some late term abortions, and delayed farrowing on some of the farms, in otherwise healthy sows, but the producers didn’t understand why at the time, Gleason said. Then the outbreaks hit.

An example he cited included a sow with extended gestation time that was induced to farrow but all the piglets were born dead. Another overdue sow was induced to farrow and had only two fetuses, both dead, which had no brains, he said.

Fetal aging was important in understanding the timing of the disease on the farms, Gleason said. The mummified fetus’ age, “puts the infection time back in early December, perhaps even late November. In retrospect, discussing it with the farm managers…it marries very well with the time that mosquitoes were worse on the farm,” Gleason noted.

As to why JEV suddenly appeared across Australia in such a short timeframe, Gleason said that there’s plenty of theories, but nothing has been proven. It has to do with environmental conditions, the sylvatic cycle of birds and the presence of the mosquitoes. In the last several years, Australia has had unexpected cycles of drought and excessive rain, “and that's possibly altered where the birds go and where the mosquitoes follow,” he said.

An early presentation of JEV during the outbreak was shaky piglets. The piglets shake, they are uncoordinated and have no suck reflex, so they end up dying, said Gleason.

The first farm with a positive diagnosis had shaky piglets, Gleason said. Those samples were collected on the 17th of January, although the laboratory diagnosis of JEV didn’t come out until late February.

“We developed an internal case definition [for JEV] of a late term abortion or an extended gestation or greater than four stillbirth or greater than four mummies or some combination of all that in the litter outcome,” said Gleason.

This compares to Australia's official case definitions for JEV, developed during the outbreak:

- A confirmed case of JEV requires recent clinical signs of disease, with a laboratory confirmation of a flavivirus (definitive JEV where possible).

- Clinical presentation 1: Reproductive disease in sows characterized by abortions, stillbirths, mummified pigs, or clinically affected, low survivability piglets, above the expected level for the enterprise.

- Clinical presentation 2: Shaking or trembling piglet, ataxic or convulsing that do poorly, with variable pyrexia.

- Clinical presentation 3: In boars, orchitis, decreased sperm number or motility in semen, or abnormal spermatozoa.

- Subclinical infection: Absence of clinical signs plus laboratory confirmation of active or recent infection.

SunPork’s affected farms all had different experiences with JEV. One farm had issues that gradually increased. Another farm had a “mummy storm,” but no extended gestation, no late term abortions, not even an increase in stillbirths.

“It was all mummified fetuses being born…it came on quite suddenly, we got up to 30% or more of litters affected,” Gleason noted.

A third farm was operating normally with no issues noticed, and then, in a single week, around 45% of the litters were affected, said Gleason.

A fourth farm didn’t have a great increase above baseline of the case definition.

“This farm had stillbirths, did not have an increase in mummies, did not have an increase in extended gestation length and had some mild deformities noticed, but definitely an increase in stillbirths,” he said.

Gleason pointed out that both curtain-sided and tunnel ventilated gestation barns were equally affected. The curtain-sided houses had the curtains open during the time when the mosquitoes were most active, so it’s no surprise the sows got infected. The enclosed, tunnel ventilated houses, however, did not protect the sows, as might be expected.

One of the affected farms has a boar stud for collecting and processing semen for internal use, he said. In early December, there were some affected ejaculates. From January through March, there were ejaculates with 0% motility and some had zero sperm. But the boars seemed fine, nothing unusual physically, no fever, none were off feed, no gross orchitis or edema of the testes. The boars, even though they have affected ejaculates, were normal and had normal libido, Gleason concluded.

National response

To control the JEV outbreak in Australia, there were two national responses running in parallel, said Richards. One on the agricultural side and one from the human health perspective. While there was national coordination, the actual implementation of measures was done at the state level, she added.

In the first few days after the first farms were diagnosed with JEV, there was rapid establishment of conditions to allow safe, controlled pig movements from the infected premises that both mitigated further risks to human and pig health from JEV, while supporting pig welfare and business continuity, Richards noted.

Key messaging in Australia focused on pork being safe to eat: JEV is a mosquito-borne disease, with pigs being an incidental host. Strong communication themes promoted mosquito precautions for people, pigs and horses, she said.

Mosquito management

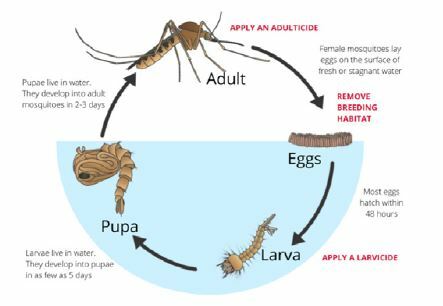

“A critical need identified within the first 72 hours of the Australian response was for guidance to pig producers around appropriate management of mosquito vectors. To put it bluntly, we weren't doing it well, if at all. At best what we were making, what we now know, were relatively futile efforts to kill adult mosquitoes rather than applying any kind of integrated effort really targeted to breaking the mosquito lifecycle,” Richards said.

A quickly assembled "vector working group” wrote a comprehensive guide for integrated mosquito management that takes producers beyond the concept of killing adult mosquitoes and addressed issues like the removal of breeding habitats and use of larvicides. The guide includes a list of chemicals and their use, as well as precautions for human and environmental safety, she said.

Farm Response

Once a farm shows clinical signs and a positive JEV diagnosis is made, infected farms must take the following actions, said Richards.

- Mosquitoes trapped, speciated and tested for JEV by human health specialists.

- Mosquito control commences or is refined to meet guidelines. This is the responsibility of the farm; required to resume pig movements.

- All personnel residing, working or contracting, on the farm are offered the opportunity to be vaccinated against JEV — coordinated by human health specialists.

- All movements of live pigs and semen out of infected premises are risk-assessed as soon as possible. Adequate mosquito control must be in place at both the departure and the destination premises. Transport of live pigs should occur during daylight hours, and pigs sent to packing plants must be processed within 24 hours of departure from their site of origin.

- No negative impact on pig welfare and very little disruption to pig movements and business continuity.

Be prepared, work together

“We learned the hard way that pigs are quite sensitive indicators for the presence of JEV,” said Richards.

“We spent two solid years engaging actively with the government in preparation for African swine fever, and not one second of that has been wasted. It might not have been African swine fever that arrived, but nothing in that preparatory work has been wasted. And the work we've all done has absolutely underpinned the collaboration and cohesion in this JEV response,” she noted.

“We've absolutely learned that relationships, mutual understanding and credibility between government and industry stakeholders are pivotal to a successful response. It's important to focus on the outcomes and be somewhat flexible around the process taken to get there. And importantly, we've learned that government and industry doing things with, rather than to, each other is key.”

Finally, “never underestimate just how many things can go wrong at the same time,” Richards concluded.