Housing and infections affect genes that regulate pregnancy in female pigs

Study also indicates that improving the environmental conditions during pregnancy reflects on the reproductive responseAt the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Science (FMVZ) at University of São Paulo in Pirassununga, research proves that the functioning of the genes involved in the pregnancy of female pigs is influenced by environmental factors such as inflammatory conditions caused by infections and deficiencies in the housing system.

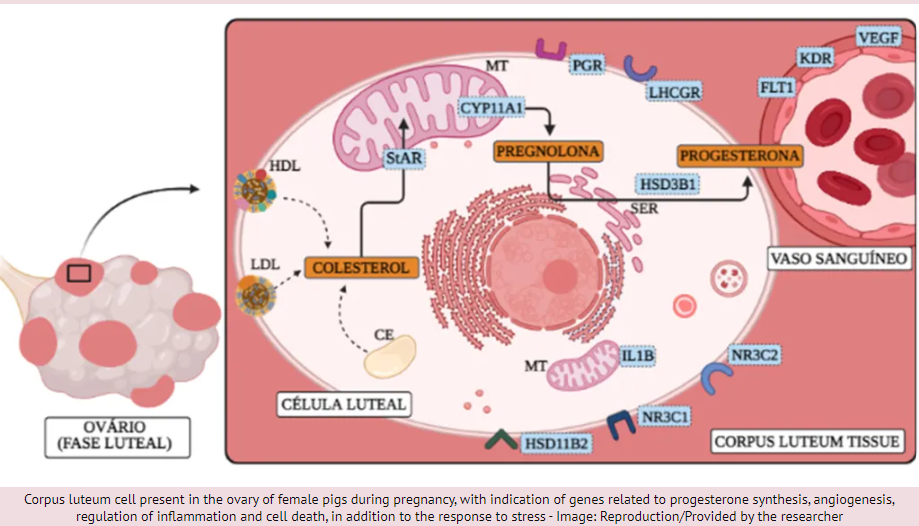

By analyzing the genetic mechanisms that regulate the corpus luteum, one of the ovarian glands, researchers point out that these factors, responsible for the occurrence of stress and diseases, can be the cause of many reproductive problems, such as deaths at birth or poor birth formation. The study also indicates that improving the environmental conditions in which pregnancy takes place reflects on the reproductive response.

According to researcher Arthur Nery da Silva, who carried out the work, the results of the study have relevant implications for animal welfare, management, health and decision making on pig farms.

“Our data is important, especially at this time when Brazilian intensive pig farming is abandoning the use of gestation crates to adopt the collective pen system, which offers better animal welfare conditions,” he told Jornal da USP. “We are demonstrating that, even though the transition from the sow system to collective pens is costly and presents challenges at first, the advantages are measurable.”

The corpus luteum is a transient gland located in the ovary.

“The longevity of the corpus luteum depends on whether or not the female is pregnant,” says Silva. “In other words, if the female is inseminated or mated by a male pig and there are a sufficient number of embryos for pregnancy to occur, the corpus luteum will remain active in the ovary, performing important and vital functions for the implantation and guaranteeing pregnancy and gestation."

The main function of the corpus luteum is to produce and secrete progesterone.

“This hormone plays an essential role in the endometrium, the inner layer of uterine tissue. Progesterone helps to thicken and make the internal uterine tissue spongy, which allows embryos to implant,” reports the researcher. “In addition, the corpus luteum also plays a very important role in regulating reproductive hormones produced in the brain, which is also essential for a successful pregnancy.”

“There is a consensus among researchers in the field of reproduction that inadequate performance of the corpus luteum is one of the main causes of subfertility and embryonic losses in species of domestic animals and humans,” said Silva. “Our objective was to understand whether external factors, such as a systemic inflammatory reaction or the female housing system, would be capable of influencing the expression of genes related to progesterone production, angiogenesis, which is the formation of new blood vessels, inflammation and apoptosis, the programmed death of cells that form the luteal tissue, and the response to stress in the corpus luteum of female pigs.”

Inflammatory challenge

In the work, the real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) technique was used to study genes with biological functions related to progesterone synthesis (STAR, CYP11A, HSD3B1, LHCGR and PGR), angiogenesis (VEGF, FLT1 and KDR), regulation of inflammation and cell death (IL1B, TNF and IFNG) and stress response (HSD11B2, NR3C1 and NR3C2) in the corpus luteum.

“The choice of the method and genes chosen to be evaluated is justifiable because we are able to verify, at the molecular level, whether physiological aspects and the development of the corpus luteum may be influenced by environmental stimuli,” said the researcher.

Among these stimuli are the type of housing (in the study, animals that were kept in gestation crates, collective pens and those raised outdoors were compared) and systemic inflammatory challenges, that is, infections that female pigs may be subject to during the gestation period.

The tissue used for RT-PCR analysis were fragments of corpora lutea.

“The corpora lutea are transient ovarian glands that appear shortly after ovulation and disappear after 12 to 15 days, if the female pig is not pregnant,” explains Silva. “To induce acute inflammatory symptoms in 18 gilts in our experiment, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was used, a molecule known to lead to a breakdown in the immune balance and harm the well-being of female pigs. Additionally, LPS also simulates one of the biggest medical challenges for females, which is bacterial urinary tract infection.”

Through laboratory analyzes of the genetic material collected from the animals, the research discovered that the VEGF and FTL1 genes, involved in the formation of new blood vessels in the corpus luteum, were significantly less expressed in the group that suffered the systemic inflammatory challenge.

“Furthermore, surprisingly, we observed that the group that experienced the systemic inflammatory challenge showed an increase in the expression of the HSD3B1 gene, which is part of the cascade for the synthesis of the hormone progesterone,” says Silva. “Our hypothesis is that the increase is actually a compensatory mechanism, as there is not a reasonable amount of blood vessels to transport the hormones produced out of the corpus luteum tissue. In relation to the female housing system, the work shows that the LHCGR gene was positively regulated among animals housed in the cage system, compared to animals in collective pen systems or outdoors. Also, we observed that animals housed in the open-air system and in collective pens showed significant differences in the expression of the STAR gene, but not between animals housed in gestation crates."

The study demonstrates that both the systemic inflammatory challenge and the housing system are environmental factors capable of influencing gene expression in the corpus luteum of female pigs.

“Although our data regarding the housing system still needs further studies to be fully elucidated, we can corroborate the idea that the better the environmental conditions offered to the animals, the better the reproductive responses obtained,” said Silva. “Furthermore, the characterization of the molecular mechanisms elucidates that, perhaps, many of the reproductive problems observed by pig farmers are caused by systemic inflammatory conditions or by the conditions in which the animals are being housed.”

The project was led by master's student Arthur Nery da Silva, with the guidance of professor Adroaldo José Zanella, both from the Department of Preventive Veterinary Medicine and Animal Health at FMVZ. The multidisciplinary team involved researchers Luana Alves, Germana Vizzotto Osowski, Leandro Sabei, Priscila Assis Ferraz, Guilherme Pugliesi, from FMVZ; Ricardo Zanella, from the University of Passo Fundo (UPF), and Mariana Groke Marques, from Embrapa Swine and Poultry. Silva received a scholarship from the Academic Excellence Program (Proex/Capes), linked to the Experimental Epidemiology Applied to Zoonoses program at FMVZ. The contribution of the male to the development of robust phenotypes and the mitigating role of the welfare of female pigs, from the São Paulo State Research Support Foundation (Fapesp) was coordinated by Professor Zanella.