How does geospatial mapping protect Pennsylvania's pigs from disease outbreaks?

At the University of Pennsylvania's School of Veterinary Medicine, researchers harness the power of real-time geospatial information systems (GIS) to safeguard Pennsylvania's farms and food supply.Tell a swine or poultry producer that their animals are sick and the first question they ask is, “How?”

Thanks to researchers at the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Veterinary Medicine (Penn Vet), producers can now get an answer to that pressing question fast – or even stop disease from encroaching past their property lines altogether.

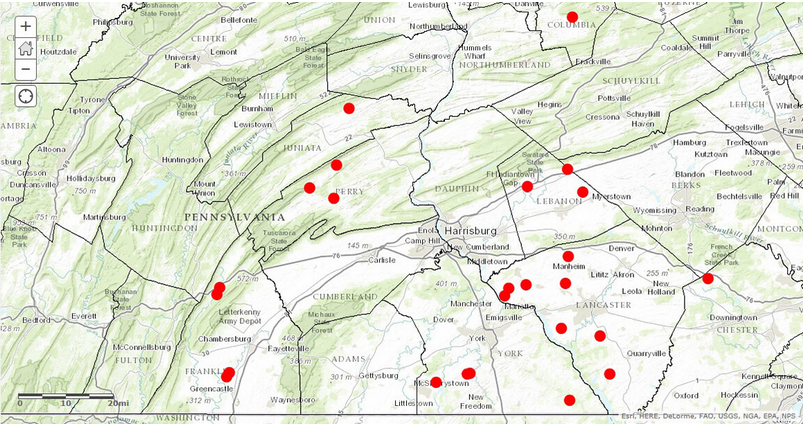

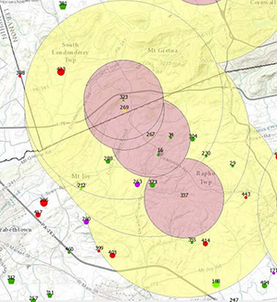

Run by Penn Vet’s Dr Meghann Pierdon, the programme relies on geospatial information systems (GIS) to pinpoint current and emerging disease hotspots, share information about outbreaks with producers, and strategise community approaches to control potentially devastating diseases. Pierdon uses the GIS data to update a secure website with a map that illustrates, in near-real time regions, where pigs or birds have tested for disease and identify areas that may be at risk. The database is updated quarterly to be sure everything is accurate and communication is open to producers.

In 2012, nearly a quarter of the swine monitored by Penn Vet’s swine disease mapping programme, called the Pennsylvania Regional Control Program (PRCP), were on farms testing positive for disease. Since participating in the PRCP, which is operated by Pierdon and funded by the Pennsylvania Pork Producers Council, that number has declined to 15 percent; 17 percent if Ohio and Indiana are included.

As a result of its success, industry participation in the PRCP has doubled to include more than 100 farmer, hauler, feed and genetics companies and veterinarian members across the Commonwealth.

The idea is to provide usable data so farmers can take the information and make informed production decisions.

“For example, we can set up protected zones where we only want negative pigs,” says Pierdon. “Producers can then make appropriate decisions based on that information, such as, being careful if buying feeders from infected areas or preventing a feed truck that was on a farm with active disease from going directly to their farm – to help cut the disease spread."

Several years ago, the first swine disease Pierdon tracked was porcine respiratory and reproductive syndrome (PRRS). Today, an emerging pathogen, porcine epidemic diarrhoea virus (PED), has caught her attention.

Most of the GIS data is drawn from Pennsylvania farms but, since neither commerce nor disease heed state lines, she also gathers information from Maryland, Delaware, and New Jersey.

On the pig side, a vet or producer fills in a template with basic data like the farm’s address, where the pigs came from and where they will go next.

“The PRCP has been instrumental in helping the industry understand the scope and impact of this new PED disease and in implementing the best biosecurity measures to stop the spread of the deadly virus,” she said.

While it is endemic, PRRS is preventable, Pierdon says. The idea is to decrease the number of farms that are impacted by an outbreak. “Then a producer can clean it up and not have to worry that it will come back,” she adds.

Most recently, Pierdon’s GIS mapping has played an integral part in safeguarding Pennsylvania poultry farms from the recent outbreak of Coryza in the Commonwealth. Similar to a head cold in humans, coryza is a bacterial contagious disease of poultry that presents with secretion of mucus deposits in the mouth and throat. The implications for production on farms whose birds have contracted the disease, however, are serious.

“It cropped up in December 2018 and progressed in number of cases until late Spring,” says Pierdon. While it slowed this summer, she is noticing and mapping an uptick in the number of cases now.

In addition to providing on-farm outreach and support, Penn Vet also works with federal and state agencies. While government tracks foreign disease threats like foot-and-mouth, Pierdon’s focus is on monitoring diseases that loom as a threat to farmers but are not reportable to the government. “It really is all about improving and implementing biosecurity,” she says, adding that the data she gathers helps agencies understand how industry is structured.

There have also been what Pierdon calls “nibbles of interest” in applying her GIS programme to help safeguard other agricultural industries, mainly aquaculture and honeybees.

No matter where the system is deployed, the main objective is to decrease the amount of disease spread and give producers control over safeguarding their farms or operations.

“We’re not just looking to respond to the disease in the moment, but ultimately, provide biosecurity solutions that can protect our animals, our people, and our environment from the next ‘big, bad bug.’”