Heritage Feeds Tomorrow: Rick Swalla’s journey as a veterinarian

Learn more Dr. Swalla's family heritage in the swine industryPart of Series:

< Previous Article in Series Next Article in Series >

Zoetis recently launched their Heritage Feeds Tomorrow campaign and Dr. Rick Swalla, Director of Pork Technical Services with Zoetis Pork, is being spotlighted because of his strong family heritage in the swine industry.

“I grew up in Stuart, Iowa on a diversified family farm, and part of my chores every day was getting up and letting the sows out so that they could eat and drink while I did the rest of my chores. Then I'd come back and put them back in the farrowing house with their pigs,” said Swalla. “Back in those days, we only farrowed once a year, so we farrowed in the spring and then took those pigs to market in the fall.”

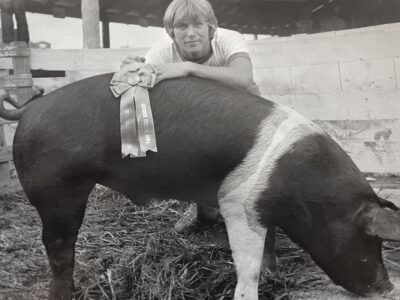

As Dr. Swalla got a little older, he joined a 4-H club and the Future Farmers of America (FFA) in high school. During his youth, he showed pigs, cattle and chickens at the county fair.

In 1982, Dr. Swalla took three pigs to the county fair and won grand champion market pig, grand champion market gilt and grand champion pen of three.

“I took three pigs to the fair and all three were grand champions,” he said. “I was really lucky. Back then we didn’t have hundreds of pigs to choose from. At that time, I had about three pigs that were that quality, so it was amazing. It was a big deal for my whole family – my dad especially. Our family had been showing pigs for years, and that’s the most success that we ever had. That sort of success was certainly unprecedented.”

As a teen, Dr. Swalla was also involved in securing a new herd boar.

“We didn't do artificial insemination (AI) back then. We went to a neighbor and found a purebred boar and did a three-way rotational cross and that would be our sire for the next year or two.”

Dr. Swalla’s dad was raised by an uncle who owned a sale barn at the edge of town. They had a flow of pigs moving through the sale barn and held pig sales every week. When Dr. Swalla’s dad got married, he actually started his farm in that same facility that was once a sale barn. He farmed there and then moved out to a farm near Madrid, Iowa.

“I grew up with a family of 13 brothers and sisters, so we had a very large family to work on the farm,” he noted. “You don't see many families that size, but we all had our chance to work on the farm over the years.”

Why become a veterinarian?

“I actually have a little poster that I made in the third grade that said I wanted to be a veterinarian, and I wanted to work with pigs, and I wanted to learn how to use medicine,” he said. “So even at a young age, I already knew what I wanted to do, and I was lucky enough to be able to follow through with the course work and get through the curriculum.”

Dr. Swalla said his career path was influenced by their exceptional hometown veterinarian, Dr. Dave Schmidt, who later became the Iowa state veterinarian. Having good mentors and great people in the industry to support him over the course of his career has been very valuable. Again, Dr. Schmidt was an important role model and teacher, and when he moved to the state veterinarian's office, Dr. Swalla had the opportunity to work with and learn from him for several years.

A changing industry

“Farming pigs has been a very large part of my life. If you think about the pig industry, it's a 24/7 business,” he said. “Even to this day, I'm available 24/7 because I know that things happen. The people in this industry have been very good to me, and they're very resilient people. Times have been tough over the years and we're having a tough year this year, but the swine industry has been very important to me.”

Dr. Swalla got his bachelor's degree in animal science and then his Doctor of Veterinary Medicine (DVM) from Iowa State University. In 1992, he started practicing as a large animal veterinarian, then in 1998 when the hog market hit $8, he went back to graduate school to focus on commercial pig production and started working only with swine in his veterinary career. He started working for Murphy Farms in 2001 and helped with the integration of Smithfield’s purchase of Murphy’s, Brown’s and Carroll’s. He said it was challenging and took some time as the industry experienced consolidation pains.

“I’ve seen the challenges and also the benefits of consolidation over the years. In the 1980s, confinement operations became more prevalent; in the 1990s genetics improved and artificial insemination took hold, and we were using boar studs,” he said.

The farms just got larger and larger. When Dr. Swalla was growing up, his family farm farrowed 8 sows at a time in a in a one-room farrowing house. Just 10 or so years later when he went to work for Murphy Farms, they had individual sow farms with more than 10,000 sows.

The industry was changing and not only in size, but disease was another component of change.

“When I graduated from veterinary school, I wrote my senior paper on modified medicated early weaning, and it was published in the Iowa State Veterinarian in 1992,” he said. “At that time, I only had about eight to 10 articles to draw from to write my senior paper.”

Since then, he’s seen the elimination of pseudorabies, lice, mange and internal parasites like whipworms and roundworms, atrophic rhinitis and Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae (APP). He also eliminated porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) from many farms that later broke back again.

“Today, Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae (Mhp) elimination is very common, and I've dealt with some Mhp-negative farms my whole career, but today Draxxin has made the elimination of Mhp a lot more effective and a lot more cost-effective than it ever has been in the past. I'm sure the next few years, there'll be other things that we are able to eliminate from the pig herd.”

PRRS was discovered in the US about the time that Dr. Swalla graduated, so he’s worked with it his entire career, but porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) is a good example of an emerging disease that he’s seen enter the market first-hand.

“Interestingly, when PED hit the industry, transmissible gastroenteritis (TGE) went away. They're both coronaviruses with a very similar niche but PED out survived TGE,” he said. “So now we have PED which is worse than TGE, but at least TGE is gone.”

How has your heritage helped?

“Having grown up on a pig farm has helped me a lot. When I go into a farm, there's no job that someone is doing that I don't know how to do and haven't done at some point in my career,” he said. “I've hired new veterinarians over the years, and I make them go through that same process. I send them to a sow farm for a week or two, and a nursery and finishing operation for a week or two.”

As new veterinarians, he said they don't necessarily appreciate that approach upfront, but they do later. For every job on the farm, you’ve got to learn how to do it and understand what works on the farm and what doesn’t work, how long it takes to do a job and what’s easy, hard and impossible for caregivers to do on the farm.

“It's very helpful to be at that point in my career where I've been through so many things. I’ve done all the jobs, and it allows me to deliver more comprehensive support and service to our customers,” he said.