Group Sow Housing: Practical Considerations

Information for producers and their advisers to help with the transition to group housing systems by Lee J. Johnston and Yuzhi Li from the West Central Research and Outreach Center at the University of Minnesota. They cover floor space allocation, feeding systems, managing sows in dynamic groups and husbandry skills.Certain segments of our society are raising concerns about the welfare of gestating sows housed in individual stalls. These folks have asked various segments of the food marketing chain to stop buying pork that is produced using individual gestation stalls. The end result is that pork producers are being encouraged or mandated to stop using individual gestation stalls, and start housing pregnant sows in groups.

One can debate the underlying motivations for this move, or the merits of such a decision, but the bottom line is that the market is driving pork producers toward group housing of pregnant sows. So how can pork producers make this major change as seamlessly as possible? The purpose of this Blueprint series of articles on sow housing is to provide producers and their advisers with ideas and resources to help with this transition.

When considering a change to group housing, the top-of-mind question for producers is: Can we reasonably expect to make this change without depressing sow performance and increasing our cost of production? This is a very difficult question to answer. Taking a very broad view of the topic, reviews of scientific studies and anecdotal reports in general suggest that there are no clear, repeatable advantages or disadvantages in sow performance when comparing group housing with individual stalls.

However, producers need to make very specific decisions about the configuration and management of a specific system.

No Standard Template for Group Housing Systems

Unlike stalled systems that are reasonably standardised and well-understood in the industry, there is no "standard" template for group housing systems. Lots of factors, such as pen configuration, flooring type, feeding system, nutrition program, grouping strategy, timing of grouping, pig flow, husbandry skills, genetics and others come together to influence the success of a group housing system.

Consequently, it is difficult to predict accurately the success of any one group housing system. There are examples of transitions to group housing that were disasters, as well as examples of very successful transitions. Focusing on key features of the group housing system will optimise chances for success.

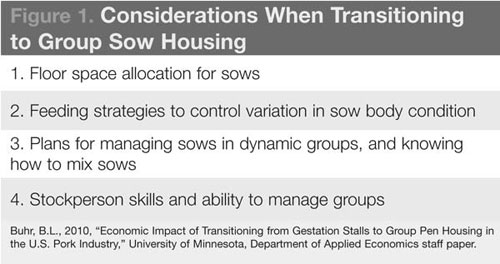

Key features to aid in successfully transitioning to group sow housing were suggested in a recent University of Minnesota study conducted by Dr Brian Buhr. In this study, a review of the scientific literature and interviews with swine industry professionals experienced in group housing were conducted.

The study uncovered four critical points that require careful consideration when moving sows into group housing (Figure 1).

Floor Space Allocation

The exact floor space allocation for sows to optimise reproductive performance and welfare is difficult to establish. Many factors, such as size or age of the sows, feeding system, group size and season interact to influence the most appropriate floor space allocation. Controlled studies, with sufficient numbers of sows to determine floor space allocations definitively, are very difficult and expensive to conduct under commercial settings. The space occupied by a standard gestation stall and half of the aisle behind the stall is about 16 square feet.

However, most studies would suggest this amount of space is inadequate for group-housed sows. In general, increasing space allowance tends to decrease aggression among sows and injuries associated with aggression, and increase farrowing rate – with few consistent effects on litter size (See Table 1).

| Table 1. Effect of floor space allowance during gestation on litter size | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Floor space in gestation, sq. ft./sow | ||||

| Trait | 15 | 24 | 35 | Stall |

| Total pigs/litter | 12.4b | 12.0b | 14.2a | 1.1b |

| Born live/litter | 10.0 | 9.5 | 10.5 | 9.4 |

| Weaned/litter | 8.6 | 8.1 | 8.8 | 8.7 |

| ab Means with different superscripts differ (P < 0.05) Salak-Johnson et al., 2007 |

||||

Obviously, increasing the floor space allowance for sows will increase building costs, so producers will not want to provide more space than is needed. When moving sows from individual stalls to groups, floor space allowances should be increased at least 10 per cent to 20 per cent. This means floor space allowance per sow must increase from 16 square feet occupied with stalls, to a bare minimum of 18 to 19 square feet.

Group size influences the proper floor space allocation. If group size is small (i.e. fewer than 10 sows), floor space allocation should be increased an additional 10 per cent because there is less total free space available in the pen.

Free space is defined as the area in the pen that is not physically occupied by a sow's body. If group size is large (i.e. more than 40 sows), floor space allocations can be reduced 10 per cent because more free space is available.

Feeding to Control Variation in Sow Body Condition

One of the biggest criticisms of group housing for gestating sows relates to the difficulty in uniformly controlling sow body condition and sow weight gain. Because sows are penned in groups, dominant sows can potentially consume more than their share of feed at the expense of more timid sows. The end result is uneven body condition and weight gain across sows within the pen. This problem was one of the important motivations to move sows into individual stalls years ago. Now, as we consider moving back to pens, this challenge reappears.

The feeding system and management of that system play a crucial role in controlling variation in body condition among sows. Feeding systems can be generally categorized as non-competitive or competitive. Non-competitive feeding systems include electronic sow feeding systems (ESF) or free access stalls. Competitive feeding systems include floor feeding, partial feeding stalls and trickle feeding systems.

The primary characteristic of a non-competitive feeding system is that sows are protected from their pen-mates while consuming their daily allotment of feed. In contrast, competitive feeding systems do not provide protection for the sow while she consumes her daily meal.

With competitive feeding systems, one sow (usually a dominant sow) can push another sow away and consume her portion of feed. Because sows are typically limit-fed in gestation, there is almost always some competition and aggression around feeding time.

With non-competitive feeding systems, this competition and aggression is controlled and kept to a minimum, unlike competitive feeding systems.

Non-competitive feeding systems have higher equipment costs than competitive feeding systems. ESFs rely on a computer to control feed delivery to individually identified sows as they stand in the protected feeder. Each sow carries an electronic identification tag that is read by the feeder, so that she can be fed according to her individual needs. The feeding station is fairly compact and occupies minimal floor space.

Free-access stalls allow sows to consume their daily feed allotment without harassment from other sows. but require a large amount of floor space. Feeding differing quantities of feed to penmates is more difficult with free-access stalls, because any sow can enter any available stall when feed is dropped. For both ESF and free-access stalls, sows must be trained to learn how to operate the feeder or stalls.

Competitive feeding systems require much less investment in equipment but offer very little protection for the sow at feeding time. Floor feeding requires feed drops and a solid portion of floor. The partial stall system is a variation of floor feeding. Feed is dropped in the front of a stall with sides that may only extend to the shoulder or mid-body of the sow. These partial stalls help prevent dominant sows from pushing timid sows away. But the dominant sow can still back out of the stall and displace a sow from another partial stall. Trickle feeding systems provide feed in small quantities at the same rate that sows can eat feed. The idea is that sows are more likely to stay in one feeding location because they know more feed will be dispensed shortly. Trickle feeding is often used in combination with partial stalls.

Competitive feeding systems have greater potential to produce greater-than-desired variation in bodyweight and backfat depth of sows at farrowing.

Managing Sows in Dynamic Groups

For competitive feeding systems to work effectively, it is important to group sows that are as uniform as possible in age and body weight. This helps control the negative effects of the “boss sow” problem. Competitive feeding systems may require more housing accommodations (stalls or small pens) for fall-out sows that do not adapt to the pen and feeding system.

| Table 2. Effect of mixing before (pre) or after (post) implantation on sow performance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Static group | Dynamic group | |||

| Trait | Pre | Post | Pre | Post |

| Farrowing rate, % | 82.5a | 85.b | 82.1a | 88.0b |

| Total born/litter | 11.9 | 12.2 | 12.1 | 12.1 |

| Born live/litter | 10.8 | 11.1 | 11.0 | 11.0 |

| ab Means with different superscripts differ (P<0.05) Li and Gonyou, 2013. |

||||

There are two major approaches to flowing sows through a group housing system: keeping sows in dynamic groups or static groups. Dynamic groups have more than one breeding group housed in a pen together at the same time. When sows in one breeding group are moved out for farrowing, a new group of recently mated sows is moved in to fill the pen. This approach is flexible and uses building space efficiently. However, sows are exposed to multiple bouts of aggression throughout pregnancy every time a new group of sows is introduced.

In contrast, with static groups, only one breeding group of sows is housed in a pen. With static groups, sows experience one bout of mixing, and the associated aggression, at the beginning of gestation. If a sow recycles or is removed for some reason, no replacement sow is introduced. So, efficiency of using pen space may suffer some with static groups.

In both approaches, sows that are unfamiliar with each other will have to be mixed together in a pen. This mixing event causes fighting that is necessary to establish the social rank among sows. Because fighting at mixing could have detrimental effects on sow performance and welfare, proper management of mixing plays an important role in the success of a group housing system.

In pregnant sows, embryos float inside the uterus for roughly the first 18 days of pregnancy. After that time, the embryos attach to the wall of the uterus (called implantation), and become more robust and resistant to stresses.

Mixing sows is a stress. Ideally, mixing sows will occur after embryos have attached firmly to the uterus. If possible, sows should not be mixed until at least 30 days after mating, when pregnancy has been confirmed. Mixing sows after implantation can improve farrowing rates compared with mixing sows while embryos are still free-floating in the uterus (See Table 2).

Stockperson Skills

Skills of the stockperson have always played an important role in sow farms using individual gestation stalls. These husbandry skills are still important in sow farms that use group housing, but the skills required are somewhat different.

Stockpeople need to employ an "animal-directed" approach to caring for group-housed sows. Workers need to understand normal sow behaviour in order to recognise abnormal sow behaviour. Once they accomplish this, workers need to learn the causes of abnormal behaviour, so that proper interventions can be put in place.

A successful stockperson needs to be open-minded about group housing and willing to learn new skills or re-learn old ones. Moving slowly, deliberately and quietly around sows will increase the bond and trust between sows and their caretakers. This trust will make it easier to move sows and work around them. Research has shown that this trust can also improve reproductive performance of sows.

When sows trust their caretakers, tasks like pregnancy diagnosis in pens can be fairly easy because sows allow workers to approach with the ultrasound unit.

Knowing normal sow behaviour can help stockpeople perform management tasks more efficiently, and with less stress on sows and workers. For instance, in a stalled system, workers can vaccinate sows whenever it suits their schedule, because sows are always in the same location and easily accessible.

However, in group housing systems, it might work best to vaccinate sows in the morning right after feed is dropped. At this time, sows are focused on eating, and will pay little attention to the stockperson or react to the injection. Likewise, checking for sows in heat might be more efficient and effective when group-housed sows are usually resting and inactive. During this time, the sow in heat is more likely to be up and more active than her penmates, and she will stand out and be easier to identify.

The National Pork Board and several universities recently completed a group of fact sheets designed to help barn workers more effectively manage individually stalled and group-housed sow gestation systems. A guide for "walking the barn" is included for each of six different gestation housing systems.

The primary difference in walking barns with pens is that sows have freedom of movement, so they will not always be in the same place each day as they are in stalled systems. This means workers need to follow the same pattern to walk the barn each day but start the pattern at a different spot each day. This will allow caretakers to see a given pen of sows at different times of the day, thus improving their chances of finding disadvantaged sows that need attention.

Each sow needs to be evaluated for body condition, health, behaviour and attitude. Workers need to ensure that the equipment - feeders, feeding stalls, gating, flooring, waterers, etc. - in each pen is working properly and will not injure sows. The air quality of the room or barn, as well as the capacity of the manure storage system, should be noticed by caretakers and adjusted if necessary.

Summary

There is no perfect housing system for sows. Each system has its strengths and weaknesses with regard to sow productivity, sow welfare, profitability and social acceptance. The mission of sow barn managers and animal caretakers is to optimize the system they find themselves working in.

Proper design of facilities is an important start but does not guarantee a successful operation. Effective stockmanship is crucial to making the facilities operate properly and ensuring sows are comfortable and productive.

This article was originally published in 'National Hog Farmer' in 2013.

Febuary 2014