Financial modeling shows real value of reformulating soybean meal net energy in swine diets

Feed invoice costs alone don’t show the revenue potential of soybean mealPart of Series:

< Previous Article in Series

Editor’s note: Bart Borg, PhD, vice president of feed and nutrition at Passel Farms in Ames, Iowa, recently spoke at the Iowa Swine Day Pre-Conference Symposium, titled Soybean Meal 360°: Expanding our horizons through discoveries and field-proven feeding strategies for improving pork production. The event was sponsored by Iowa State University and U.S. Soy.

Dr. Borg shared a recap of what he’d heard from previous speakers at the Soybean 360° symposium, and then tied it all together answering the question “What does this all mean for swine diet formulations?” showing the impact on swine diet formulations and the need for more extensive financial modeling “beyond the invoice price” of cost and revenue.

Key messages from the conference’s speakers:

- Increasing crush capacity will provide a greater volume of soybean meal that may carry a lower, more attractive price relative to recent history

- A recharacterization of soybean meal is necessary as new information continues to grow suggesting soybean meal:

- Is higher in net energy than previously recognized, especially in a commercial environment

- Contains beneficial functional bioactive compounds

- Should be the primary amino acid source in summer formulation strategies to reduce the summer carcass weight dip

- Nutritionists and producers alike should keep an open mind about soybean meal and consider what the pig is telling us in the studies

Opportunity to reassess swine diet formulation

“It's important to understand the higher net energy component of soybean meal,” said Dr. Borg. “If we change the net energy content of soybean meal within the formulation process, we will have a different interplay with other ingredients and their net energy if we're balancing to a minimum net energy content.”

There are also several things that are outside of the formulation process that need to be accounted for. Besides the constraints put on the formula, there's a need for modeling that includes revenue and goes beyond the cost impact of the diets.

“For example, if you're formulating with a minimum for an isoflavone, you have to account for that outside of the formulation process as there may be some mortality benefit or other aspects we don't quite understand today,” he explained. “Plus, there's a good opportunity for soybean meal use being the primary amino acid source, especially during the summer to help producers avoid the summer weight dip.”

Making a profit

“The feed formulation process helps us get to a feeding program, but it leaves us only with a cost,” he said. “We're putting constraints on the nutrient content of the diet, nutrient content of ingredients, ingredient costs, and ingredient minimums and maximums. This creates an invoice price, but the revenue calculation needs to occur outside of the formulation process itself.”

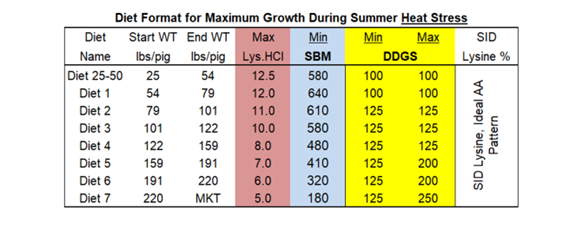

The chart above shows that if we use this summertime feeding strategy, it includes a maximum level of dried distillers grains (DDGs) that are probably lower than what would be used today based on the invoice price because replacing DDGs at their current price is sure to drive the formula cost down.

“Outside of the formulation process activity that needs to go on, will with added gain, turn us to a greater revenue capture situation. The chart above has minimum soybean meal content across diets, maximum levels of crystalline lysine being suggested and maximum levels of DDGs,” he said. “There's a minimum level of DDGs listed because of the gut health aspects that have been shown in some research relative to DDGs. So, as we begin to talk about formulation, we need to keep an open mind and look at it with a fresh outlook.”

Formulation specification decisions

In rethinking the net energy change in soybean meal, there are several things to consider.

“Unfortunately, if we all left the room today and said, ‘yes, we're all believers in higher net energy,’ we can't assume that tomorrow pigs are going to be converting that to 15 points better feed conversion just because we've decided soybean meal has changed in value,” he said. “The pig has been consuming that higher net energy soybean meal, and it's us as nutritionists and scientists who need to recalibrate around the studies that have created lysine-to-energy ratios that we think are right today.”

There are some options to consider about how to handle this formulation.

- Maintain the SID lysine-to-net-energy ratio.

- Maintain SID lysine specifications and let net energy float. If that's a small enough amount, you may have a one- or two-hundredths of a percent that you're adjusting SID lysine.

- Recalibrate to a new SID lysine-to-net-energy ratio.

Ultimately, the two options are to recalibrate or to get a little bit more accurate.

- Option 1: Recalculate the lysine:calorie requirement curve using the new energy value of soybean meal.

- Option 2: Maintain current dietary lysine level. This approach allows for a “new” lysine:calorie ratio to be generated from formulation considering the soybean meal inclusion level in the current diet and new dietary energy content.

Formula analysis

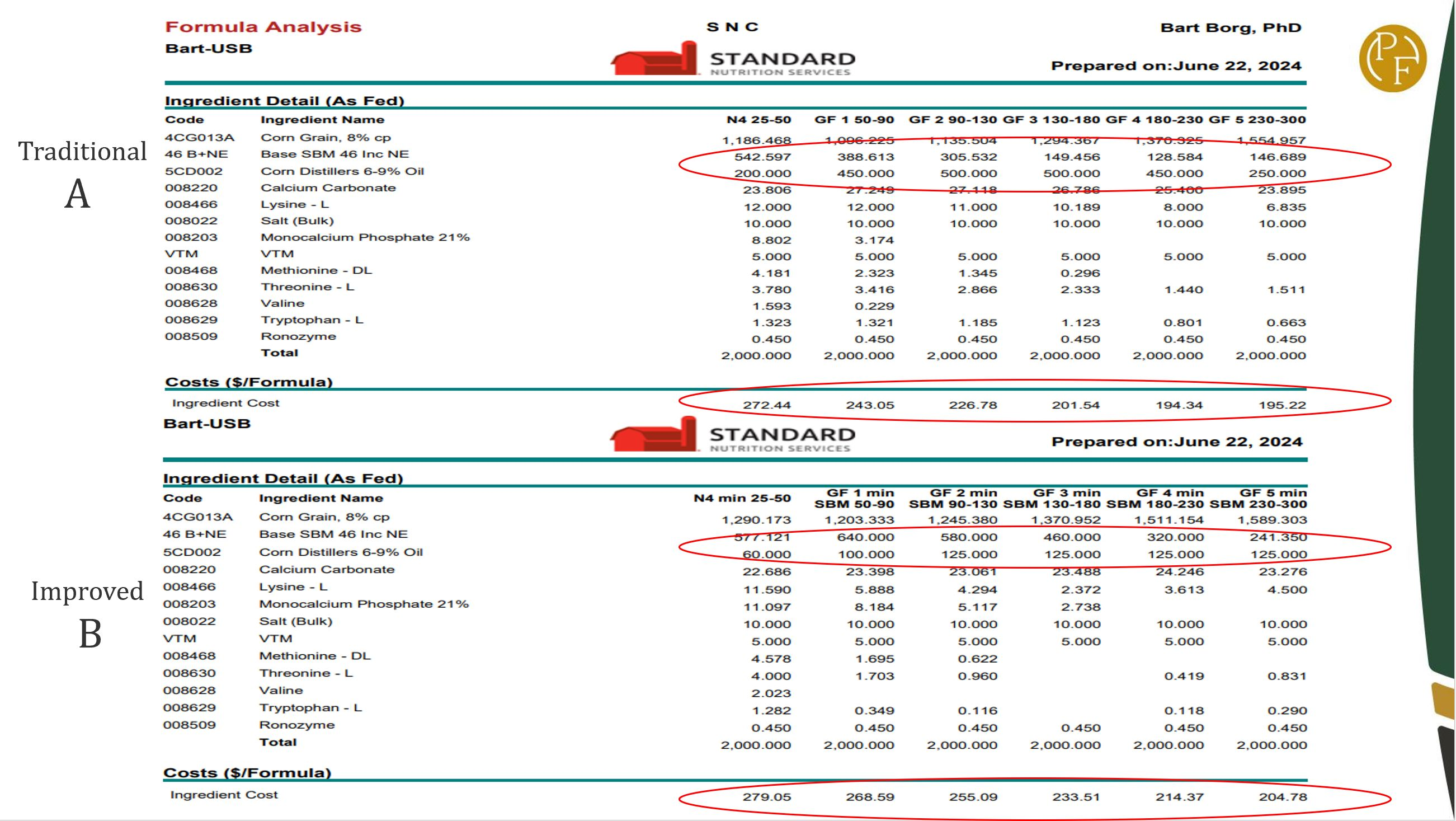

Dr. Borg begins this discussion by considering two diet formulations – a traditional formulation versus a minimum soybean meal or ‘improved’ diet. The traditional program uses DDGs starting at 200 lbs. in the late nursery diet going up to 400 to 500 lbs. then settling into 250 lbs. for the last finishing diet. Ingredient costs range from $195 to $272.

The minimum soybean meal ‘improved’ diet content uses a maximum DDGs level of 125 lbs. Looking specifically at the first grower diet, it’s a $243 cost in the traditional diet compared to a $268 cost in the minimum soybean meal ‘improved‘ diet.

“There’s quite a difference in cost between the diets that are formulated to the same specifications. If you've got a producer who is focused on ingredient cost, remember that, as a nutritionist or advisor, you need to remind your producer that there's a revenue component to be considered in the final equation. In the end, the invoice price of the feed doesn't guarantee a positive revenue.”

What are the cost and revenue bucket considerations?

In the cost bucket:

- Pig

- Feed, which is 70% of the cost of producing a pig

- Housing and care

- Medication

- Transportation

In the revenue bucket:

- Live sales of market hogs

- Sales of culls and light and heavy pigs

“A goal is always the opportunity to shift the weight curve to get more pigs in the sweet spot of the packer grid which can be a revenue source if you're able to have more pigs in that premium spot,” said Dr. Borg.

On the cost side, the primary drivers of the cost/revenue change include the feed price, made up of the ingredients and formulation, and pig performance in a given environment which includes average dairy gain (ADG) in a “fixed time” system and mortality.

On the revenue side, there’s carcass price, carcass weight and number sold as full value pigs.

Calculating cost/revenue

Dr. Borg shared an example of how to build a financial cost/revenue model using the buckets outlined earlier:

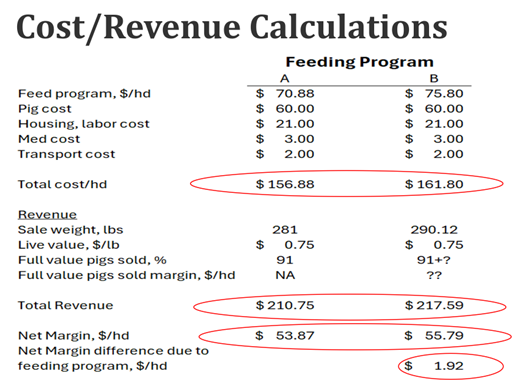

A traditional feeding program (titled A in the chart) and the minimum soybean meal ‘improved‘ feeding program (titled B) shows a feed cost of $70.88 for feeding program A and $75.80 for feeding program B, the ‘improved’ program.

“If you stop there and just look at feed, you'd say go with program A, but you haven't considered total revenue,” he said. “By adding up the other costs, program A ends up costing $156.88, while program B costs $161.80. If we add revenue in and consider what could be a weight change difference, there’s an opportunity to get additional revenue. For total revenue, we have $210.75 for the traditional program A and $217.59 for program B, the ‘improved’ program. The net margin shows a $1.92 per pig advantage for program B, primarily due to the additional revenue gained in weight.”

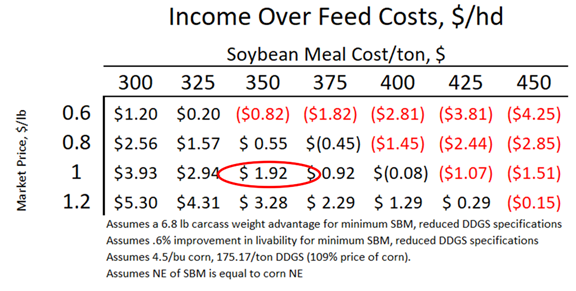

These numbers, like any modeling scenario, can change every day due to commodity price changes and market price changes. This is why models need to be dynamic and looked at consistently. In the example above, the $1.92 per head advantage should be considered an estimate. This spreadsheet can easily be set up in Excel.

By setting up a sensitivity table, you can identify different iterations of the model that work and others that don’t work because at some point the value of the soybean meal weight advantage isn't going to overcome a cost of diet difference and that needs to be considered.

“It offers different ways of expressing and getting accuracy of what are you modeling and gets you as close to real-life production as possible,” he noted.

In summary, Dr. Borg said nutritionists need to keep an open mind about the new research that is coming to light showing that net energy is higher in soybean meal than previously thought. He reminds nutritionists that the formulation exercise is just a portion of the work that needs to be done to determine the most cost-effective feeding program. Areas of potential revenue difference between feeding programs must be considered, such as carcass weight, market sales considering the potential for mortality change and percent of full value pigs.

“I think there's a real opportunity for a new industry modeling tool to be created that can assist in the decision-making process, perhaps similar to what Kansas State, PIC and Iowa State have created that brings it all together,” he said.

Click here to learn more.

Brought to you by U.S. Soy. Fully funded by the National Soybean Checkoff.