African swine fever in wild boar: environmental resistance

Characteristics of the African swine fever virus circulating in Europe and AsiaEditor's note: the following is an excerpt from African swine fever in wild boar populations - ecology and biosecurity. It was created by the FAO, WOAH and European Commission. Additional content from the booklet will be shared as an article series.

The extreme environmental resistance of the African swine fever (ASF) virus is the key to understanding the epidemiology of ASF and developing adequate measures and interventions for its control, both in the pig production sector, and under natural conditions when it circulates in wild boar populations. Currently available information on the potential of different matrices to facilitate spread of the virus is provided in Box 1, and fully listed by Fischer et al. (2020).

Two points deserve special consideration. First, most of the literature describing the tenacity of the ASFV is based on virus detection with a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test. However, the detection of its genome does not necessarily mean that a live, infectious virus is present in the animal. The virus genome can be detected even when the virus itself is not viable, and thus no longer infectious. Only virus isolation proves the viability of the virus, and is a more sensitive diagnostic method than PCR testing; however, virus isolation is difficult to routinely perform, and is therefore much less frequently used for diagnostic purposes at present (Fischer et al., 2020).

Second, any environment (such as the central European continental platform) is composed of a number of ecosystems (i.e. forests) that contain a number of habitats (i.e. broad-leaved deciduous trees), each subdivided into a number of microhabitats. While abiotic factors (such as sunlight, radiation, temperature, humidity and air composition) are largely shared in the environment, each of the habitats and microhabitats is characterized by specific characteristics such as pH, retained humidity and solar exposition. The thousands of square kilometres of forests in central and northern Europe consist of a wide range of different microhabitats in which the virus can persist for a variety of periods, while infected wild boar (as live animals) continue to spread the virus or contaminate the environment (as carcasses). Both environmental complexity and diversity guarantee – together with these infectious wild boar and contaminated carcasses – the continuous presence of the viable virus, and the consequent risk of repeated reinfection, determining the wild boar–habitat cycle.

In any ASF-infected wild boar population, there are seven categories of animals, each with a different epidemiological role in spreading the disease. These categories are:

Susceptible: Any healthy individual that has never been infected by ASFV and is thus susceptible to it. Such animals normally comprise the largest part of the population. The number of susceptible animals changes seasonally due to reproduction and mortality, with the latter largely due to hunting, though predation, limits on food resources and disease may also contribute.

Incubating: Any individual that is infected but does not yet show visible clinical signs of the disease. Incubating animals could spread the virus for a number of days (usually one) before showing evident signs of the disease. The number of incubating animals is usually very small (usually less than 2 percent) and is dependent on the phase of virus invasion, the season and other factors. The only way to determine if a hunted wild boar is in the incubation phase is to collect samples and conduct laboratory testing; positive animals should be safely destroyed. However, during the incubation period, especially during the first days, no virus can be detected. Usually the virus is detectable between the end of the incubation period and the beginning of the clinical phase, in the very early stage of which signs can still go unnoticed.

Diseased: A wild boar showing clinical signs of ASF, or appearing healthy but, when tested, shown to be virus positive. In experimental conditions, wild boar show clinical signs for 4–9 days before death (Nurmoja et al., 2017a); 90–95 percent of diseased animals die (Pietschmann et al., 2015; Nurmoja et al., 2017a). Clinical signs are not pathognomonic, instead being represented by many possible abnormal behaviours (such as lack of escaping, trembling of hind legs and prostration) that simply indicate that the wild boar is sick. Sick animals could be more prone to predation. In the hunting bag, the average virus prevalence ranges from 0.5 percent to 2.5 percent; however, according to local sampling strategies or specific epidemiological situations it could be higher, for example 13.7 percent in southern Estonia (Nurmoja et al., 2017b). The true proportion of virus-positive animals in the population can be under-represented in the hunting bag as sick animals deviate from their predictable behaviour, changing their daily routines, losing appetite and shifting to inaccessible parts of their territory, all of which prevent them from being easily hunted. Only laboratory tests can verify if a wild boar is infected with ASF, and if positive, it must be destroyed. Any wild boar killed in a road accident in ASF-affected or at-risk areas should also be tested.

A wild boar infected with the Caucasian strain of genotype II has a limited probability of survival; however, seropositive animals do occur in low numbers where ASF is present in wild boar populations. For the animals that survive the infection, the scientific literature describes three distinct occasions when serological tests may turn positive, of which only the two latter are observed with genotype II:

Chronically sick (Sánchez-Vizcaíno et al., 2015; defined as Category 1 by Ståhl et al., 2019): Animals with a reduced lifespan that host the virus for the rest of their life. These animals shed the virus when showing clinical signs and/or ASF lesions. The animals show as positive according to both PCR and antibody tests. There is no evidence that the ASF Caucasian genotype II induces the chronic form of the disease.

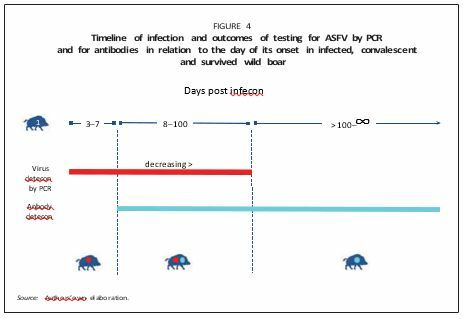

Convalescent (defined as Category 2 by Ståhl et al., 2019): Animals that completely recover from the infection and will not show any clinical signs or lesions. ASFV remains attached to the external membrane of the erythrocytes, the lifespan of which determines the presence of the virus in the blood. There is no evidence that these animals became long-term spreaders of the virus. They become virus negative at around 96 days after infection (Nurmoja et al., 2017a; Petrov et al., 2018). Often, convalescent animals are wrongly regarded as “carriers” (similarly to foot-and-mouth disease carrier individuals), but they are not capable of playing this specific epidemiological role (Figure 4).

Seropositive: Animals that have survived the disease and, when tested, appear to be antibody-positive only. They are resistant to reinfection, at least from the same strain of the virus, against which antibodies were developed. In infected areas, the proportion of seropositive wild boar in the hunting bag ranges from 0.5 to 2 percent; however, the number of seropositive animals is correlated with the duration of ASFV persistence in the area. Thus, increased seroprevalence reveals an endemic stability rather than an attenuation of the virus virulence. While seropositive animals no longer shed the virus, the viable virus could be still detected in their lymph nodes (Wilkinson, 1984; EFSA, 2010a); hence, they must be considered as potentially infective and thus whenever hunted and testing as seropositive for ASFV, should be safely destroyed in the same way as virus-positive animals.

Dead: The majority of wild boar infected with ASFV die (ASF has a case fatality of 90–95 percent) and remain in the environment for some time, providing a significant source of infection for other wild boar. The simplest and most frequent way of identifying the potential presence of ASF in an area is through hunters or other people visiting wild boar habitats finding carcasses, which can then be tested. Any dead wild boar should be removed from the forest and safely destroyed, as well as tested for the presence of ASFV or other pathogens. Although in any wild boar population there is always a proportion of animals that die naturally without any infection from ASFV (Keuling et al., 2013), as an ASF epidemic unfolds the number of carcasses increases substantially, thus signalling the incursion of the virus or, more often, an ongoing epidemic. In Europe, the detection of ASF-infected carcasses increases from winter through spring and summer, peaking in July and August. These observations reflect certain patterns of the disease transmission cycle and population dynamics, as well as the cumulative effect of climatic and seasonal factors on carcass decomposition and the probability of their detection by people.

In a wild boar population, the virus is shed by:

- Incubating animals, during a very short period before the appearance of clinical signs. As this phase is rather short, it is of minor importance in the whole chain of ASF infection.

- Sick animals, towards the end of the clinical phase. Shortly before the animal dies, virus shedding reaches its peak.

- Convalescent animals, which have survived the acute/subacute stage of infection. These can spread the virus for some time; the virus is attached mainly to the erythrocytes (95 percent), and to a lesser extent, white blood cells (1 percent). During this period, the virus is shed only through blood, for example from wounds resulting from fights among wild boar.

Reference

Guberti, V., Khomenko, S., Masiulis, M. & Kerba S. 2022. African swine fever in wild boar – Ecology and biosecurity. Second edition. FAO Animal Production and Health Manual No. 28. Rome, FAO, World Organisation for Animal Health and European Commission. https://doi.org/10.4060/cc0785