Combining pigs with crops can make sustainable sense

Is it possible to devise a sustainable system for pig production that is profitable and can apply at every scale of production? Farming methods that combine rearing livestock with growing crops or forest management might offer a solution.Contributing to global food security

For the past 20 years the ambition to eradicate global hunger has been the UN’s declared aim, as set out in the organisation’s Millennium and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). To accomplish this, intensification, the process of producing more output with the same or less input, was at first broadly encouraged – and the pig sector has been very proactive in this respect. Recently, however, especially since the announcement of the SDGs in 2015, focus has shifted to increasing sustainability rather than continuing with further intensification. Sustainability is based largely on the so-called “triple bottom line” of people, planet, profit, where businesses place considerations such as societal impact and environmental footprint on an equal footing with financial viability. The long-term consequences of intensive production often prove to be in conflict with this approach – intensive agriculture can be unsustainable in terms of use of resources, pollution, disease spread, financial income and social well-being. This calls for systems or adjustments that will bring us closer to a production approach that is still profitable and will prove socially beneficial for generations to come.

Pigs as soil improvers: “A digger from the front and fertilizer from the back” (Sepp Holzer) © Irene Camerlink

Sustainable pig farming

Agropastoral and silvopastoral systems are good examples of such production methods. Agropastoral systems combine keeping crops with rearing livestock, while silvopastoral operations combine livestock with forestry. These systems take a holistic view on production and pay attention to nutrient balances and closed cycles. The output of one aspect – for example manure from livestock – is aligned with the input required by another aspect, such as fertiliser required for crops.

This combined approach has many similarities with organic farming, but need not be limited to organic operations. In practice the way it’s implemented varies widely both between and within countries, and depends on farm size, the types of crops or trees involved and the types of livestock being reared. One may think of livestock in Africa, backyard farming of pigs in Asia or traditional farming in Europe, but also large-scale modern farms. In these combined systems pigs are an excellent choice as they digests crop leftovers, weeds and other low-value nutrients into high value protein for the plants.

Managing pigs and plants together

A profitable rotation can be made between crops and pigs. Once the crops have been harvested the pigs can roam that patch of land to clear up the leftover crops, remove weeds and loosen the soil and fertilise it. Once they have cleared the patch, the pigs move to the next field while the previous one can be sown with new crops.

This rotation means that almost year round the land can be used in a profitable way. It does take some careful management, adjusted to the seasons and climate, but such a system can help make a farm’s income less susceptible to market fluctuations. Instead of producing for one market with its ups and downs, there is a spread over various markets, which can compensate for the reduced prices of one sector.

Alentejano pigs grazing between oak trees in Portugal © Irene Camerlink

Forest pigs

Several good examples of silvopastoral systems that feature pigs can be found in parts of Spain and Portugal, where pigs roam between oak trees (photo 2). In spring the pigs feed on grass, which is supplemented with some dry feed, while throughout winter they fatten on the acorns from the oaks, creating an extraordinary flavour in the meat. The pigs are deliberately fed to grow slowly to improve the meat’s flavour, and the meat is sold for a premium price – up to €500 per ham.

The number of pigs that can be kept depends on the amount of land available, the productivity of the trees and the consumer demand for premium pork. The pigs also clear the forest of underbrush, thereby preventing the occurrence of large wildfires in this dry and extremely fire-sensitive area. In cases where the land is populated by cork oaks, the trees provide an extra source of income from the cork. A nice video of a silvopastoral system in Spain can be seen on the Association of Celtic Pigs Breeders’ website.

Pigs at Fulin farm, China, are both valuable pork and good soil improvers © Irene Camerlink

Fusion of modern large-scale commercial and agropastoral methods

Creative farmers show that it can be highly successful to combine agropastoral principles with modern commercial farming. An example of this can be seen at the Fulin Black pig farm in China. The farrow-to-finisher farm, which has 2,000 sows, an in-house slaughterhouse and extensive retail, seems far from the typical agropastoral system, yet it successfully applies the same principles. Growing pigs and gestating sows are kept in groups of 70 in large, open-sided pens with a canvas roof and a deep layer of river sand (photo 3). With 4m2 per animal, the pigs are clearly happy, with space to run and dig in the sand. Conventional gestation and farrowing crates are still there for the sows.

When the pigs are sent for slaughter the pen is disinfected and left to ferment. After a month, crops such as radish, celery, green onions, spinach and strawberries are planted on the sand (photo 4), with the choice of crop adjusted to benefit from market prices. Soil samples show that there is no pollution in the soil or crops.

The farm uses the local Black pig, of which the pork is worth three times more than the commercial White pigs. As consumer demand is less than the supply, some sows are inseminated with commercial breeds and the piglets sold as commercial stock. Given Fulin’s turnover of millions of yen, it’s clear that this system is highly profitable, and it’s likely it would be so even at a smaller scale, or if a commercial breed were used.

Crops planted where there were first pigs © Irene Camerlink

The future for some or for many

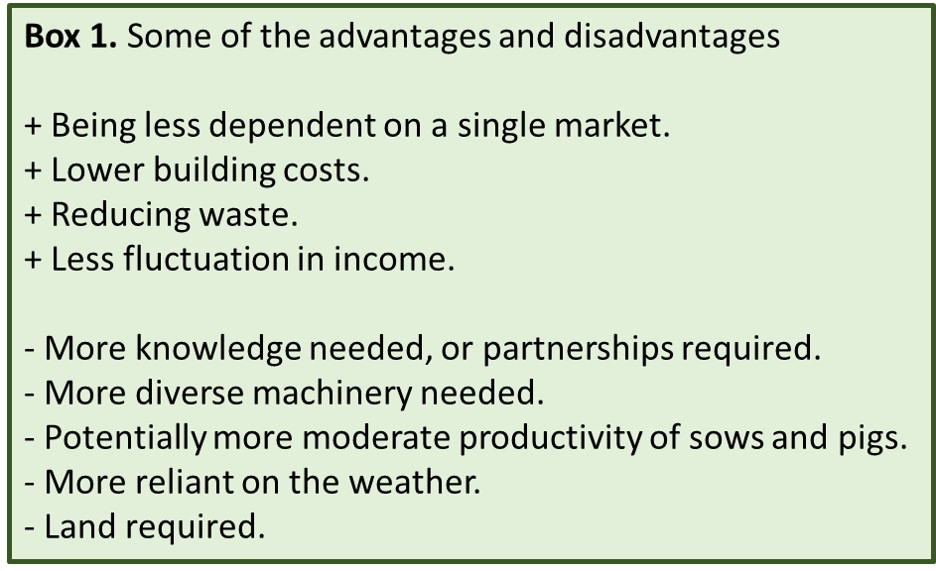

Listing the advantages and disadvantages (box 1) of agropastoral and silvopastoral farming, or a combination of both, it’s clear that these approaches might not be the best fit for every farmer. But the option of taking useful elements of from them and implementing them in commercial farming is worth considering.

When it comes to large-scale farms where the owner’s task is to manage employees, skills in managing people, finances and logistics are often more important than having all the hands-on skills. This is exactly what these combined systems need: a good manager who balances all the inputs and outputs to create a system where “waste” serves as a valuable input for the parallel component.