African swine fever in wild boar: is eradication a solution?

So far, extermination has only worked on islands with an organized, long-term effortEditor's note: the following is an excerpt from African swine fever in wild boar populations - ecology and biosecurity. It was created by the FAO, WOAH and European Commission. Additional content from the booklet will be shared as an article series.

In light of the expanding epidemic of ASF in Europe, voices have been raised in favour of extermination of wild boar as a pest or an invasive species (as in Australia, the United States of America and other areas outside of its native range in Eurasia). In some of the affected European countries this question has already provoked considerable debate in the media among game management professionals, hunters and veterinarians. This is not surprising considering that in northern and eastern Europe wild boar are a highly valued game species, whose extermination is quite reasonably opposed by the hunting community. That community is perceived to be responsible for the management of game species, and veterinary authorities often make formal requests that they carry out depopulation or extermination campaigns.

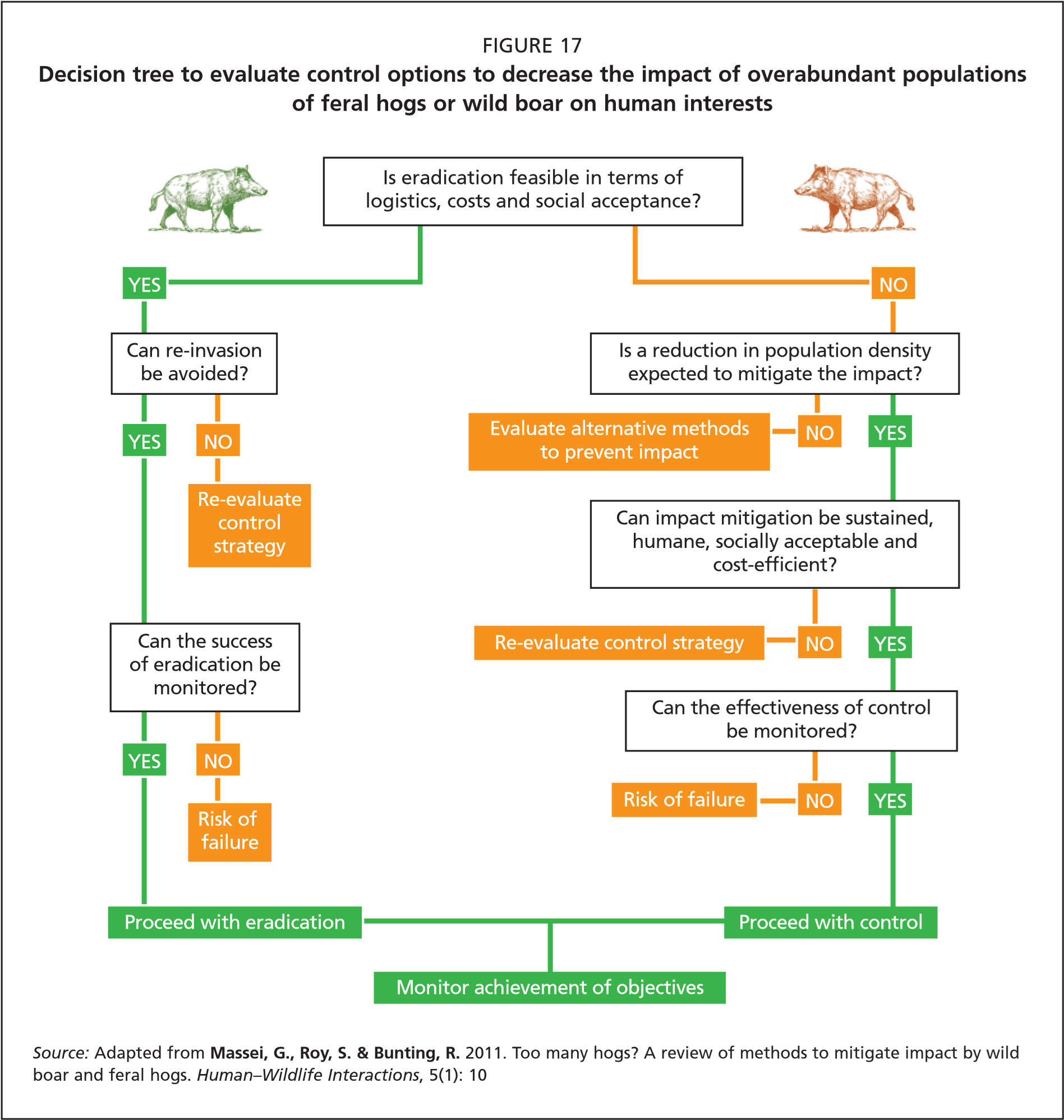

Experience shows that extermination of wild boar was feasible only on islands and as a well-organized, systematic and long-term effort (Massei, Roy and Bunting, 2011). The main lessons to learn from attempts to eradicate this species are that they can succeed only when: i) social acceptance; and ii) logistical and economic prerequisites for such a campaign are in place; and when iii) reinvasion of this species can be effectively avoided; and iv) monitoring of eradication success can be ensured (Figure 17). In northern and eastern Europe, fulfilment of these four basic requirements cannot be achieved, with even less likelihood of achievement in western Europe.

In the biological sense, wild boar are not an invasive, or non-native, species in the northern and eastern European ecosystems (Heptner, Nasimovich and Bannikov, 1961); therefore, their eradication inevitably conflicts with national nature and wildlife conservation legislation.

It is difficult to reach a consensus on these issues among the respective authorities, academia and non-governmental organizations (Danilkin, 2017). Although local extinction of wild boar can be achieved, reinvasions from other areas will occur, quickly decimating all eradication efforts. Existing population monitoring methods are not sensitive to low densities of animals and cannot verify the success of eradication with the required level of confidence.

In some eastern European countries, ASF is endemic in pig populations (EFSA, 2010a, 2010b, 2014, 2015, 2017; Khomenko et al., 2013); thus, even when wild boar are absent, the infection can remain a threat for long periods of time in domestic pigs and contaminated by-products.

Therefore, based on ecological, epidemiological, practical and ethical considerations, extermination of wild boar as a species anywhere in northern and eastern Europe should not be viewed as a principal or a key solution for ASF. Rather than making decisions that create a complex collision of interests among stakeholders, it is more appropriate to try to change hunting management practices, to reduce the size of the wild boar population for a period of time to manage the situation with ASF, and to take precautionary measures to avoid spreading the disease (see later sections of this chapter and chapters 4 and 5).

Why conventional hunting fails to control wild boar population growth

The exact demographic mechanisms behind positive population balance of wild boar may differ between parts of Europe (Gamelon et al., 2011; Servanty et al., 2011). However, in general, it is evident that contemporary hunting pressure, the main source of mortality in wild boar, cannot stop the population growth of this species. Although in some countries hunting wild boar is permitted without restrictions and occurs all year round, the feasibility of a significant increase in hunting seems to be low (Massei et al., 2015). Apart from the demographic aspects, the natural resilience of wild boar to hunting pressure is facilitated by complex behavioural responses such as individuals learning to avoid risk, changing activity patterns, home range sizes and habitat preferences. Wild boar often take advantage of the network of protected areas and concentrate around urban or buffer zones along State borders where hunting is prohibited, restricted or otherwise problematic. Large crop fields, particularly those of ripening maize, are another type of shelter where animals can avoid hunters and stay out of reach for extended periods of time.

In the temperate forests of northern and eastern Europe, hunting wild boar is recreational and occurs mainly during autumn and winter months, when it is more practical and efficient. The most effective hunting occurs in a relatively narrow window of 3–4 months. Even if hunting takes place all the year round, the bulk of the hunting yield is nonetheless amassed during the traditional winter gaming season. For the majority, hunting is a recreational activity and a supplementary business activity for gamekeepers and hunting organizations. For the latter, wild boar are an important economic resource that is purposely managed, protected and exploited, often with remarkable investments of money, time and labour.

In this particular system, non-professional hunters expect easy and predictable encounters with wild boar with little investment of time dedicated to searching for animals. Therefore, game managers typically aim at increasing the density and survival of wild boar populations and in this way ensure stable services, attractiveness and the economic sustainability of their seasonal hunting business. The most widespread management approach to achieve these results with the free-living populations is provision of supplementary feeding and shooting restrictions on adult females to ensure ethical hunting practices are employed.

Is population control of wild boar a panacea for African swine fever eradication?

So far, there is no empirical evidence that eradication of ASF from wild boar populations can be achieved on a large spatial scale through a significant reduction of their numbers. The experience from Czechia and Belgium summarized in chapter 4 serve as examples of eradication of ASF from wild boar following focal introduction and localized spread.

It requires extraordinary effort, resources and an unprecedented level of coordination. However, population management and hunting practices in Europe need to account for the presence of this important pig disease within ecosystems to minimize the negative impact of risky activities.

The most challenging aspect of ASF epidemiology is the capacity of the virus to survive for a long time in the environment, particularly in or in association with carcasses of wild boar that have died of the infection. Because of this complication, the disease transmission cycle only partially depends on the density and interaction patterns of live animals. Apparently, both long-term survival of the virus and involvement of the carcass-to-animal transmission mechanism make it possible for the disease to circulate even at low wild boar population densities.

Research and statistical simulations based on current understanding of ASF epidemiology in wild boar showed that population management measures potentially available to limit the spread of ASF should be exceptionally drastic (EFSA, 2017). Under the conditions found in the disease-affected countries in Europe, to prevent the spread of the virus in stillfree areas – with an average abundance of one to two animals per square kilometre – a preventive reduction by 80 percent of the actual, real number of wild boar in the area over four months within a 50-km zone adjacent to the infected area would be required to prevent the propagation of the virus. In the areas where ASF is already endemic, the same de-population level cannot guarantee the eradication of the disease due to the presence of infected carcasses.

Alternatively, targeted hunting of reproductive females and a ban on supplementary feeding could be applied for a minimum of three years in a buffer zone of 100–200 km surrounding ASF-infected areas to halt the geographical spread of the infection to the free areas. However, it must be stressed that there is limited experimental evidence regarding the success of either of these approaches in the control of ASF in wild boar. Furthermore, no minimum population density threshold to stop transmission of ASF has been reliably identified to date (see chapter 1).

The general lesson from the computer simulations is that a combination of several measures most suitable or feasible for a particular context should be applied at the same time (EFSA, 2017) as a potential solution for lowering wild boar numbers where this is considered beneficial for reducing the risk of infection.

Population reduction and control are the measures that can help to decrease disease burden and the risk of its spread but only in combination with a variety of other interventions, including strict biosecurity during hunting, fencing, removal and safe disposal of infected carcasses, effective surveillance and overall good cooperation and coordination of efforts among wildlife authorities, game managers, hunters and veterinary professionals.

Guberti, V., Khomenko, S., Masiulis, M. & Kerba S. 2022. African swine fever in wild boar – Ecology and biosecurity. Second edition. Chapter 3. FAO Animal Production and Health Manual No. 28. Rome, FAO, World Organisation for Animal Health and European Commission. https://doi.org/10.4060/cc0785