African swine fever in wild boar: African swine fever management

Tip to manage ASF virusEditor's note: the following is an excerpt from African swine fever in wild boar populations - ecology and biosecurity. It was created by the FAO, WOAH and European Commission. Additional content from the booklet will be shared as an article series.

The presence of ASFV in any wild boar population is a serious animal health threat for the sympatric domestic pig population. In the European Union, almost all domestic pig outbreaks occurred in areas where ASF was present among wild boar. In the absence of an effective and safe vaccine and due to strict international trade limitations imposed on an infected area or country, the presence of the virus in wild boar populations has very serious negative economic implications for the pork industry. While the complete eradication of the virus is the desirable outcome of management interventions, experience shows that it is neither a quick nor easy solution to the problem. ASF eradication in wild boar has proven to be a serious challenge everywhere and failures to achieve this strongly outnumber successful eradication campaigns. In most cases, virus eradication is simply not possible for various reasons, such as the lack of resources to manage very large infected areas inhabited by thousands of wild boar, or the nature of the wild boar’s habitats, where the active search and removal of carcasses is complicated and cannot be sustained (e.g. wetlands, mountain areas, border areas, minefields).

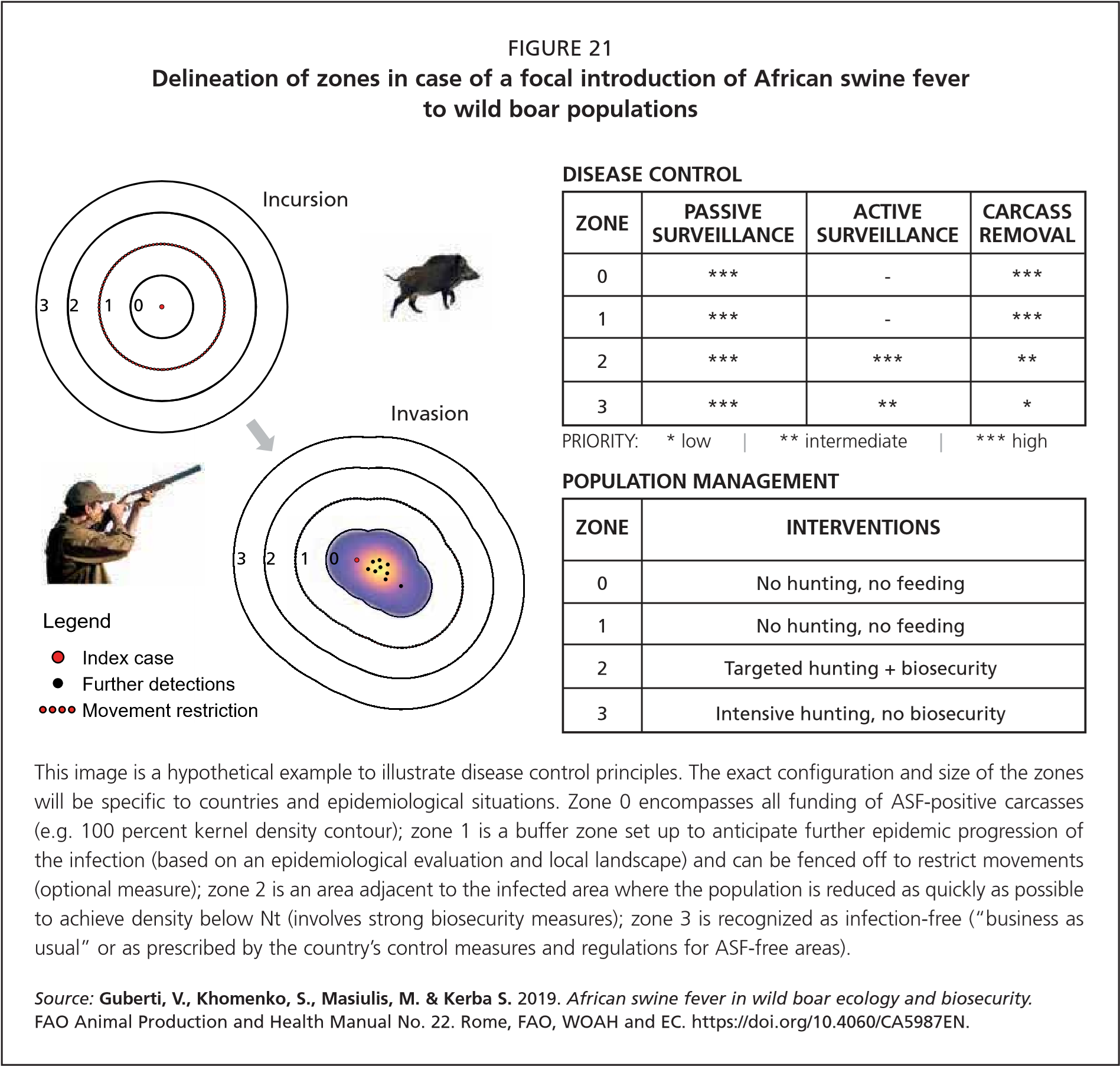

Three main ASF strategies have been used (Table 3) in attempts to reduce prevalence, limit the spread or eradicate the disease in wild boar. Eradication was only successful in relatively small infected areas (< 1 000 km2) where fencing was possible, which somewhat contributed to the other measures being carried out.

Aim of African swine fever management

For ASF management to be successful, it should aim to:

- Halt the geographical spread of the epidemic wave. If the epidemic wave is not halted, the process of virus eradication will inevitably fail and the size of the infected area will grow indefinitely.

- Eradicate the virus in the area the epidemic wave has passed through and where the virus is reaching an endemic status.

Immediate actions following first case detection

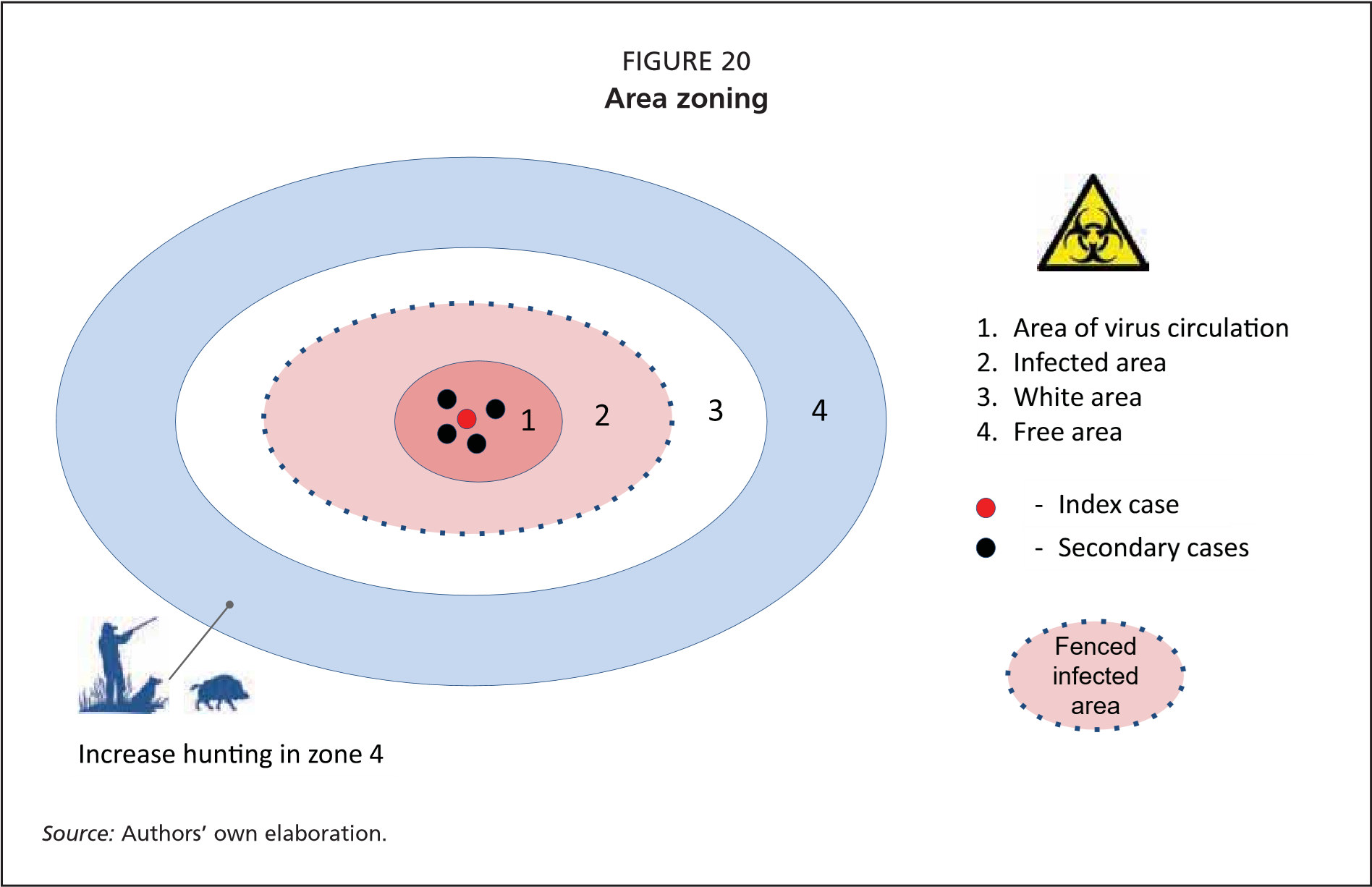

Following the detection of the index case, almost all usual forest, agricultural and leisure activities should be banned and the size of the area under restriction defined by landscape characteristics and the geographical distribution and abundance of the wild boar. Active searches for carcasses should provide key epidemiological information on the local evolution of the ASF epidemic. In practice, active searches for carcasses, sampling and their safe disposal should be the only activities permitted and must be carried out by trained personnel. To avoid disturbance, prevent long-distance movements of wild boar and limit virus contamination of hunting tools, vehicles and dressing rooms, all hunting activities should be banned in infected areas (zones 0 and 1, Figure 20). Feeding should be strictly prohibited throughout all zones to minimize contact rates between animals attending feeding sites and to eradicate any positive demographic effects on the wild boar population related to supplementary feeding. Logistics and biosecurity measures should be identified and implemented to ensure the safe removal of carcasses from the infected area (zones 0 and 1, Figure 20) until an ASF-free status is regained, which could require years of effort.

Defining areas

The primary objective of zoning is to define the spatial distribution of the virus and thus improve actions according to the risk posed by the presence of the virus, including the protection of the domestic pig population, as well as the eradication strategy of the competent authorities.

Area of virus circulation

Once the first infected animal is detected (index case), the priority should be to further delimit the area of virus circulation. This area is the convex polygon defined by the most external ASF-positive carcasses. The active search for wild boar carcasses (passive rather than active surveillance with hunting) should be immediately organized to better understand the spatial pattern of the infection around the index case. The logic behind this search is that the first detection of ASFV likely represents a much larger situation (Figure 20). To accomplish this epidemiological recognition phase usually takes around 3–4 weeks. All positive carcasses must be fine-scale mapped and the convex polygon must be drawn with a surrounding buffer area. The role of this buffer area is to account for the likely extent of the spreading wave of the virus given the apparent duration of the epidemic. The size of the buffer area can be identified based on: i) the size of an average annual home range of a wild boar; or ii) the expected speed of the epidemic wave (in Europe this is estimated to vary between 1 km per week and 1 km per month) (zones 0 and 1, Figure 20). The applied constant for this exercise was 6 km wide, which corresponded to the maximum annual home range of an adult male wild boar (6 x 6 x 3.14 = 10 000 ha) or a few months of an epidemic wave progression. The procedure should be repeated whenever new positive detections are reported outside the infected area (zones 0 and 1), with the zoning areas updated accordingly.

Infected area

Once the real extent of virus circulation is revealed, the “infected area” must be defined. This area is created based on the likelihood that the virus will geographically progress during the implementation of the containment or eradication campaigns. All ASF containment or eradication measures, including restrictions to domestic pigs, should be applied to the entire infected area. The size of the infected area should account for the size of the area of virus circulation. The infected area should be largest in size. The exact ratio between the sizes of these two areas is lacking, but experience shows that the size of the infected area should be at least twice the size of the area of virus circulation. It is highly recommended that the border of the infected area be shaped according to the presence of natural or artificial barriers and taking into account various other epidemiological considerations (season, population density, duration of the epidemic, availability of resources, anticipated duration of the management efforts, among others). As experience shows, artificial or natural barriers will not definitely halt the epidemic wave of the virus, but may contribute to the success of disease management interventions. The primary role of such barriers is to slow the spread of the virus, allowing for more time to implement appropriate management interventions aimed at adjacent areas (surrounding areas inhabited by ASF-free wild boar populations). In any case, ASF eradication is only achievable if the epidemic wave of the virus spread is successfully interrupted.

White area

The aim of creating and including a white area in the ASF management processes is to obtain a “wild boar vacuum” so that the infected population can be isolated, thus breaking the chain of the infection responsible for the epidemic wave. To halt the epidemic wave, the size of the white area should be planned to obtain the quasi-extinction of the local wild boar population. Too large an area means the wild boar population size is too big to manage, too small an area means there is potential for wild boar to escape the infected area and also for the local redistribution of animals, which could hinder management efforts. A quasi-extinction means that the wild boar population is no longer viable, despite some individuals still being alive. In epidemiology, the wild boar quasi-extinction density level does not enable virus transmission.

White area borders are defined through four main approaches:

- implementing administrative borders or weak geographical barriers (in this case the virus always bypasses the area);

- fencing off the area of virus circulation encircled within an infected area and very large white area (e.g. in Czechia);

- fencing off the whole infected area and building several small extra fences in the white area, which depends on the spatial evolution of the epidemic (e.g. in Belgium);

- fencing off a strip of forest (a few kilometres) to separate the infected wild boar population from the healthy population, while culling the boar inside the fenced forest.

African swine fever-free surrounding area

An ASF-free area is set out at the external border of the white area. In ASF-free areas, hunters are required to increase hunting efforts (i.e. double the previous year’s kill). While competent authorities supervise all activities carried out in infected and white areas, activities in ASF-free areas are carried out as part of usual hunting activities (with the sole exception of an increased effort). The size of ASF-free areas varies and issues addressed in such areas mainly concern wild boar management rather than disease control.

Once the zoning has been completed, competent authorities must decide if they plan:

- To contain the infection and possibly regain ASF-free status through medium-term wild boar population management. The strategy implies a certain period of endemic presence of the virus, which means that it could only reduce the speed of the epidemic wave, rather than halt it. As a result, the infected area tends to progressively enlarge, though not as quickly as when left unmanaged.

- To eradicate the virus through a short-term wild boar management strategy and regain ASF-free status through the local quasi-extinction of the infected population. The strategy is based on spatially isolating the chain of infection (hence stopping the epidemic wave) using boar-proof fences and reducing transmission inside the fence (R0 < 1).

The choice between the two different management strategies requires an assessment that should consider – among other circumstances – the size of the infected areas, economic implications and the impact on the pig industry, the numbers and geographical distribution of domestic pigs, the number of hunters and the wild boar density and available financial and labour resources. Actions should be carried out for at least one year following the detection of the index case, meaning volunteers should not be the sole labour force for carrying out disease control interventions.

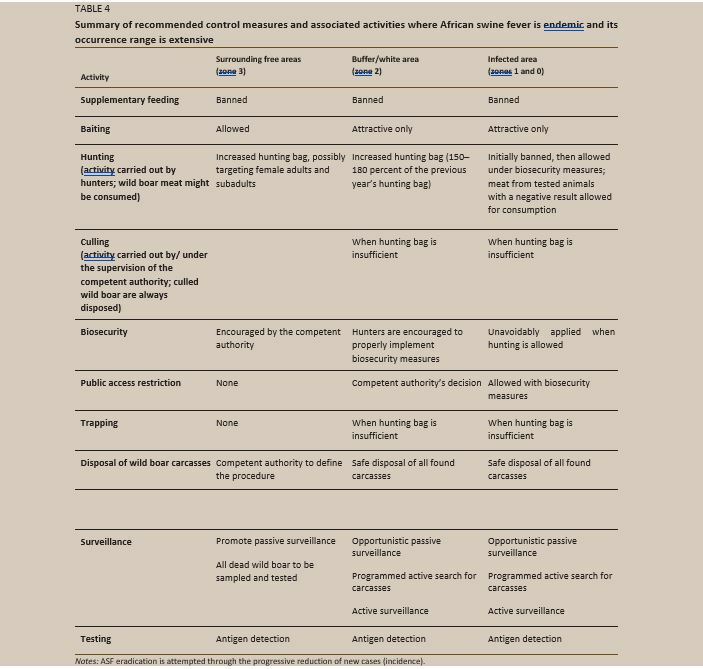

Containment followed by eradication

The aim of this strategy is to contain the virus inside the infected area, while strongly reducing wild boar density in the white (if defined) or ASF-free surrounding areas. The gradual reduction of the wild boar population (both inside and outside the infected area) through the targeted hunting of adult and subadult females, the safe disposal of carcasses and the application of biosecurity measures during hunting should drive ASFV to extinction. Unfortunately, according to European experience, this strategy tends to maintain an endemic equilibrium for years, which increases the risk of the virus escaping outside of the infected area. Table 4 shows the main measures that are implemented.

Eradication achieved through the extinction of local wild boar populations

This strategy uses fences to achieve eradication. Boar-proof fences are erected to delimit areas where all wild boar should be culled by specially designated teams, tested and then disposed of regardless of the test results. Usually, public employees (e.g. foresters, gamekeepers, snipers) cull the wild boar in the area. This depopulation effort is a special measure that requires extremely high biosecurity standards of conduct. Provided that the extinction of the local wild boar population is successful or at least achieves a significant reduction in numbers, passive surveillance should be established. This surveillance should aim to exclude the possibility that the virus escaped from its known circulation zone to the white area. In white areas, the wild boar population is rapidly reduced by any legal means, but never through driven hunts. The quasi-extinction of the infected wild boar population requires spatial isolation (quarantine). The combination of management actions coupled with the lethality of the virus should result in virus eradication.

Area adjacent to the infected area

A very strong reduction of the wild boar population is desirable in areas that are adjacent to the infected area. Whenever possible, recreational hunting pressure should be increased. Further economic incentives may stimulate the active participation and involvement of hunters and subsidies can help maintain local venison markets. The reduction of wild boar populations can only be considered effective when hunting bags grow by a factor of at least 1.8 compared with the previous year. To avoid excessive testing of hunted wild boar, areas adjacent to the infected area should be carefully monitored for any wild boar carcasses (see the section on surveillance). However, if hunted animals are to enter the market chain, every wild boar should undergo PCR testing and receive a negative ASF result.

The proposed containment and eradication of ASF are largely based on the epidemiological considerations and principles described in previous chapters. The approach should be implemented and fine-tuned according to the local epidemiological landscape and adjusted following the evolution of the disease.

KEY MESSAGES

- ASFV can only be detected early through passive surveillance.

- At the end of the epidemic, passive surveillance is the only strategy that can demonstrate the elimination of the virus.

- Passive surveillance is also key to determining the different zones through which the infection in wild boar populations can be managed.

- ASF eradication is possible if two concomitant goals are achieved: halting the geographical spread of the virus; and drastically reducing the number of infected wild boar in the endemic area through which the epidemic wave was passing.

- ASF eradication is possible through the progressive reduction of virus incidence or through the quasi-extinction of the local infected wild boar population.

- The progressive reduction of virus incidence is possible through carrying out targeted hunting of adult and subadult females, the strict application of biosecurity measures during hunting in the infected area and an increased hunting effort in ASF-free surrounding areas.

- The eradication of the virus through the quasi-extinction of the local infected wild boar population is possible through fencing and rapidly culling the wild boar population surrounding the infected area.

- Eradication is only possible when a complete set of measures is applied to both the infected and surrounding areas.

Guberti, V., Khomenko, S., Masiulis, M. & Kerba S. 2022. Chapter 4. African swine fever in wild boar – Ecology and biosecurity. Second edition. FAO Animal Production and Health Manual No. 28. Rome, FAO, World Organisation for Animal Health and European Commission. https://doi.org/10.4060/cc0785