Advances in food scanning might spell the end for product recalls

Along with a host of other applications for the pork sector, the highly sensitive scanning technique of hyperspectral imaging promises to make food impurities a thing of the past.

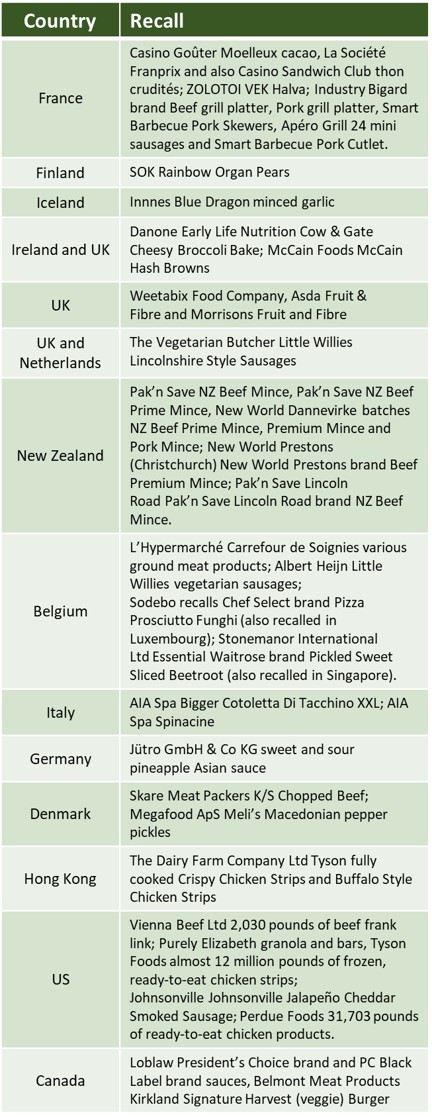

Source: eFoodAlert

In May 2019 alone, there were recalls of at least 40 different food product across 16 countries (10 of them in Europe) due to foreign-matter contamination. Among the assorted debris, pieces of plastic, rubber, glass, bone, packaging and metal all made their way into a wide range of finished products that went out for consumer purchase. These products were mostly pork and other meat items, but also included vegetarian products, cacao, granola, pizza, pickles and much more (see below for the full list).

Some companies around the world, however, have already secured their processing lines against this kind of contamination, by installing hyperspectral imaging systems. The technology is also being used to assess the tenderness of pork and poultry meat, and some systems, in addition, allow food processors to assess and manage the composition of their products, identifying for example, the amounts of protein, fat, bone and water they contain. Hyperspectral imaging is also being used to detect pathogens in poultry meat.

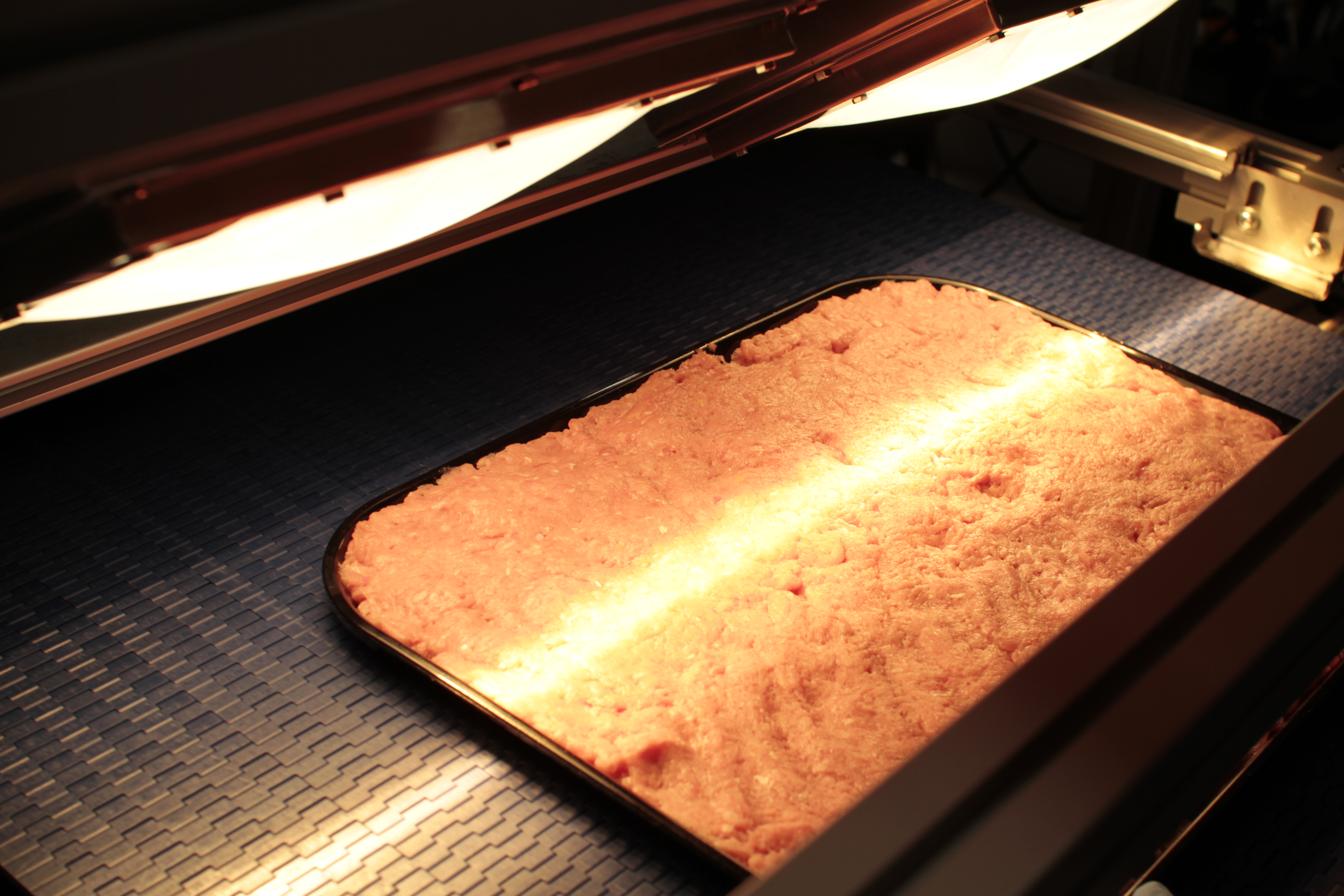

Hyperspectral imaging involves scanning food products across a wide range of the electromagnetic spectrum and analysing the “image” produced to look for imperfections and other elements of interest. By projecting and detecting wavelength bands at a fine resolution from both the visual and non-visual parts of the electromagnetic spectrum, a hyperspectral sensor collects enough detailed data from the object to create a unique “fingerprint” for any product, such as a pork cutlet or minced pork. In scanning subsequent items, any material that stands out as unusual from the standard fingerprint is easily and identified. The process involves large amounts of information being gathered and processed instantaneously, making it well suited to automated systems where the readouts can be acted on in real time.

© Treena Hein

Hyperspectral imaging has many uses in agriculture that are already in place or in development. Besides food processing and packing lines, it can be used to detect debris at harvest, to determine crop plant health and to identify animal proteins or contaminants in livestock feed. In human medicine, use of the tech for early diagnosis of various organ diseases is now being explored. The technology also can be used to identify various minerals in geological samples, to monitor emissions from factories, incinerators and other facilities and to detect temperature differences in all sorts of situations. It also has applications in the analysis of banknotes and coins for authenticity, and in remote sensing, including military surveillance. A variety of cutting-edge uses of hyperspectral technology were presented at a global conference in April 2019.

Compared to other methods currently in use for detecting undesirable material, hyperspectral imaging is a significant and powerful step forward. Visual inspection is inconsistent, and in the course of examining products workers may actually contribute foreign matter (for example, when workers accidentally scissor off small pieces of their rubber gloves). Scanning systems that use X-rays don’t detect materials such as plastic and are also unable to identify small pieces of bone or cartilage. Metal detectors, meanwhile, are only able to identify metal fragments. In the end, even companies that deploy all of these traditional sensing systems may still miss foreign materials.

Hyperspectral imaging in use

P&P Optica, a Canadian hyperspectral-technology firm based in Waterloo, Ontario, started trialling its “Smart Imaging System” in both Canada and the USA three years ago for poultry, meat and produce applications. It is now building systems for commercial deployment.

© P&P Optica

The applications of most interest to P&PO’s pork clients, says Heather Galt, vice president of marketing, are quality measures such as water content, pH, colour and grade, as well as composition, in trim, bacon and product blends.

In February, the government’s export-credit agency, Export Development Canada, announced a $1 million investment in P&P Optica to help the firm expand into international markets. “Over the past months, we’ve invested heavily in growing our presence in the US market, and our first few commercial systems will be installed in both Canada and the USA,” says Galt. “We are focused primarily on the meat industry at the moment, with pork and poultry representing our two most engaged markets.”

The first applications will be foreign-object detection, but the firm’s systems are flexible so they can be upgraded to measure composition of both trim and product blends, as well as tenderness and many other attributes. “We have heard interest in inspecting sausages for casing removal and/or casing flaws,” says Galt, “but we aren’t currently working with any customers for this particular application.”

Boston, Massachusetts-based Headwall Photonics has installations in Canada and the US for meat, fruit and nut analysis, including some at Ocean Spray (cranberry and other fruit products) and the Bratney Companies (a large food-processing firm).

In 2014, Headwall Photonics entered a licensing agreement with the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) for poultry processing, and it continues to work with the USDA (primarily in Athens, Georgia) on the detection of septicemia-toxemia at the carcass level. It has other customers using its technology to evaluate poultry wholesomeness – assessing how healthy-looking carcasses are, and spotting signs of disease such as skin tumours – and for grading cuts of pork and lamb.

While the technology is expensive and it will take time for it to become fully established in the pork sector, its extraordinary sensitivity compared to traditional methods of weeding out food contamination is obvious. As hyperspectral imaging is further adapted more applications in food processing are found, we’re sensing this can only be a good thing for consumers and producers of pork alike.