A Perspective of Stockpersons and the Humane Euthanasia of Swine

The role of the stockperson in the humane killing of pigs is explained by Madonna Gemus-Benjamin and Scott Kramer of Michigan State University (MSU), Alastair Bratton (Verus Health Alliance) and Tina Conklin (MSU Extension) in the latest issue of 'MSU Pork Quarterly'.Introduction

As farmers, you are one per cent of our population who knows what it means to care for a living animal meant for food. You are able to extend compassion and respect to the animals in your care while making life and death decisions on a daily basis. A farmer’s desire to see their animals prosper and doing what is right for the animal’s quality of life can create a “caring-killing” paradox.

In this article, the intention is to provide the authors' current perspective on humane euthanasia for swine, including the role of the stockperson; the present choices available; research on human characteristics and coping strategies for the stockperson; and methods available toward evolving the perceptions swine euthanasia, so they are seen more as humane endings.

The Stockperson

A farm owner or employee, who works with livestock such as pigs, is considered a “stockperson.” Notably, high quality stockpeople working in pig production raise the standard of animal performance and make the business more successful (1). Studies have shown that the successful stockpersons are conscientious, caring, eager to learn, humble, careful observers, empathetic, and have a positive attitude. All of these attributes correlate to both improved productivity and animal welfare.

Understandably, stockpersons whose work involves euthanasia of an animal, may experience significant levels of grief and/or distress. A considerable amount of research has been conducted among animal shelter workers, veterinarians, and other animal caretakers on their reactions to euthanasia. These studies have revealed reactions of anger, sadness, fear, guilt, depression and helplessness.

Surprisingly, there is limited scientific research on how the pig stockperson feels about the euthanasia process. One survey study (2) found that employees prefer a method of euthanasia that is perceived as less painful and stressful and were more accepting of the task as long as the animal appeared sick. Women and Spanish-speaking stockpersons were less positive on the task of euthanising pigs. It is interesting that while most respondents of an employee survey did not have a problem performing euthanasia, the longer an employee’s job duties included euthanising pigs, the less willing he/she was to euthanise.

Experience would strongly suggest that people who enjoy working on farms and are respectful toward animals often have a difficult time making the timely decision to euthanise. Terry Whiting in an article for Livestockwelfare.com believes there are six human barriers to euthanasia: holding onto the faint hope of the animal recovering; ignorance; lack of training and equipment; lack of empowerment; shirking or repugnance of killing; and moral food conviction – an abhorrence of wasting an animal for use as food (3).

We wonder if the way that a stockperson is required to perform euthanasia might instill an inner psychological conflict. In psychology terms, this is known as cognitive dissonance, which is the mental discomfort experienced by an individual who holds two or more contradictory beliefs, ideas, or values at the same time (3). When this is experienced, individuals tend to become uncomfortable and they are motivated to reduce this dissonance, as well as actively avoiding situations and information, which might increase it. In euthanasia, one of the outcomes of this dissonance is that euthanasia, especially methods like Manual Blunt Force Trauma (MBFT) are performed incorrectly. With MBFT, frequently not enough force is used, or employees did not stay to monitor the pig afterward.

Because other employees are experiencing the same dissonance and are dealing with it in similar ways, these incorrect practices can become generally accepted in a farm’s culture. This causes a deterioration in euthanasia practices that can go unnoticed because the change may not be easily recognized within the group of employees all sharing in the dissonance. Eventually, these practices can deteriorate to a point that we might be surprised or shocked to see “normal” industry practices on undercover expose.

Coping with Euthanasia-related Stress

When dealing with this difficult but necessary task, it is very important, that managers create a barn culture where the stockpersons feel comfortable voicing their attitudes and those who are unwilling to perform euthanasia procedures on pigs should not be forced to do so. The stockperson may find it difficult to find others who can listen, without judgment. Often in barns, there is an expectation of “toughness” and stockpersons who struggle with euthanasia can fear being seen in a negative way or not successful in their work. Farm managers should observe their stockpeople for signs of this aversion or reluctant exposure to euthanasia, especially signs of dissatisfaction with the work or careless handling of pigs.

Individually, we all find ways of coping with the stress of euthanasia. A number of studies (5-8) have indicated the possible ways that employees and stockpersons managed that stress included:

- separation or avoiding euthanasia tasks

- wry humour

- recognition that euthanasia is humane, necessary and important

- gained competence and confidence through training that the euthanasia was done well

- a calling to a moral obligation to “do it correctly”.

Stockpersons

Advances in science and technology continually provide new opportunities as well as new products, equipment and techniques for the swine industry. While the recognition of a sick animal may seem like “second nature” to some, it is not to others. Through proper training we can help the stockperson to establish on-farm protocols, decision trees, and “rules of thumb” on making the best decisions around euthanasia when the pig has little or no chance of recovery.

Training

According to the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA), timely humane euthanasia is recommended for pigs when “death is a welcome event and continued existence is not an attractive option for the animal.” Some veterinarians have suggested that employees are not always properly trained to recognise when an animal is losing weight or getting sick. The following are “rule of thumb” characteristics may help stockpersons recognise when euthanasia should be considered:

- inadequate or minimal improvement after two days of intensive care.

- pigs may exhibit extreme weakness or inability to eat or drink.

- severely injured or non-ambulatory pigs with the inability to recover.

- suffering from any infection or disease which fails to respond to treatment.

- a 20 to 25 per cent loss in total body weight resulting in a body condition score of 1.

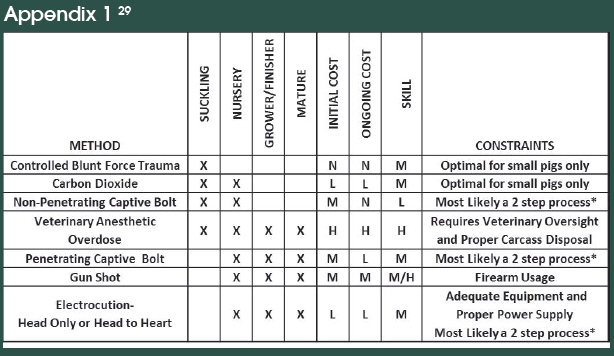

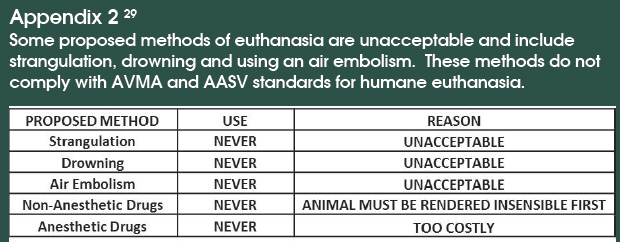

The National Pork Board (NPB) and the American Association of Swine Veterinarians (AASV) has provided a very thorough publication entitled, “On-farm Euthanasia of Swine – Recommendations for the Producer”(written materials are available through NPB’s “pork store” or by contacting the Michigan Pork Producers Association office) which provides a description of eight acceptable methods of swine euthanasia for pigs of different weights summarised in Appendix 1 (9). It should also be noted that there are proposed methods that should never be used as means of euthanasia. These unacceptable or unwise methods are presented in Appendix 2.

According to swine stockperson survey, employees viewed euthanasia training as beneficial especially when completed on-farm and by a company trainer. An effective preparation for training stockpersons on humane euthanasia requires a Euthanasia Action Plan on each farm to improve timeliness of euthanasia and reduce uncertainty in the method and skilled required for euthanasia. All individuals conducting euthanasia must be trained to be aware of the methods available, perform the techniques with care, efficiency and personal safety while avoiding additional fear or stress on the animal. If you are uncertain of your current practices and/or skills as a trainer or would appreciate an on-farm evaluation, contact your local veterinarian or extension agent for more information.

Demonstrate

When choosing a tool, it must be kept in mind that s that are unpleasant to operators/observers. It is important to choose the appropriate tool for these reasons when deciding on an individual on-farm method. For example, the practice of Manually Blunt Force Trauma (MBFT) is becoming less tolerated by consumers, customers and stockpeople of the pork industry. Sadler, Johnson and Millman have recently published an excellent overview of alternative methods to MBFT for piglets weighing up to 12 pounds (10).

Alternatives to MBFT include captive bolt methods. Based on recent studies, euthanasia of piglets during he farrowing and nursery phase can be conducted using a non-penetrating captive bolt method (NPCB) developed in conjunction with the University of Guelph and Bock Industries. The barrel of the gun is placed flush on the frontal bone, between the eyes, in the direction of the tail. The conical shaped head of the bolt impacts the skull, without breaking the skin, causing concussion and brain damage, then retracts back to the original position.

The tool, the Zephyr–EXL has been shown to be highly effective for euthanasia of both neonatal and older piglets up to approximately 20 lbs (11-13). This is an advantage of this technology as MBFT is not recommended for use on pigs that weigh more than 11 lbs. A penetrating captive bolt, such as the Blitz gun, is less preferable for use in young pigs due to concerns for operator safety and the unsightly open wound left by the penetrating captive bolt. The Zephyr-EXL allows for euthanasia of piglets in farrowing barns as well as those transitioning into the nursery (that weigh less than 20 lbs). Piglets classified as weak, lame, or having hernias at the time within the first four weeks of movement into the nursery are likely candidates for euthanasia.

Another advantage to the usage of Zephyr-EXL is that the stockperson can use a two-shot approach until they are comfortable with the new technique, achieving rapid insensibility and brain death while minimising pain and distress of the pigs. In one of the studies (13), two older piglets required a second or repeat application of the NPCB. Since the Zephyr-EXL does not require calibrating or reloading, the two shots can be fired quickly, with the second shot serving as a precaution to ensure sustained insensibility until death in 99.3 per cent of pigs (13). The average cost of the Zephyr-EXL, with air compressor, is $1,300.

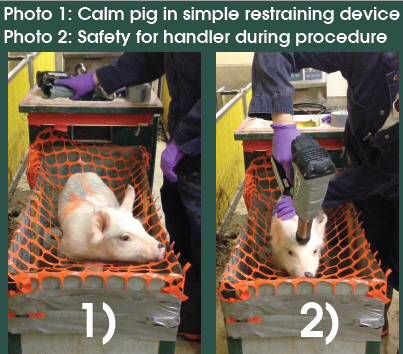

Another concern within the studies was the ability for the stockperson to properly place the NPCB gun flush against the skull while restraining the pigs. Recognising the need for a restraining method that would reduce operator error and increase safety while using NPCB guns, farms within Alberta introduced a prototype restraining method that appears to calm the pig while allowing safe restraint. The restraint is modeled after the concept of slings. By using mesh, netting or fencing, the pig can be placed such that the belly is supported and legs are suspended.

Based on the authors' observations, the pig is both calm and restrained within the device (Photo 1) and the handler has adequate and safe access to the pig to conduct humane euthanasia with one or even two shots (Photo 2). For more usage information on the Zephyr: bit.ly/ZephyrTool. Please note that the NPCB device in these photos are with a product similar to the Zephyr-EXL.

Follow-up

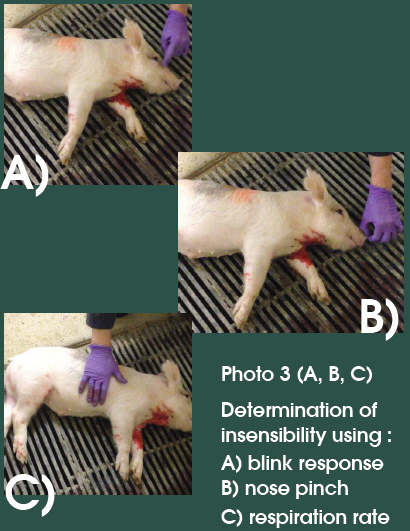

The goal of euthanasia is that the loss of consciousness or sensibility which should occur within seconds. A pig is considered insensible (Photos 3 A, B and C; 11) when they:

- lack a blink response when either the eyelid or cornea is touched,

- lack a response to a nose pinch

- lack rhythmic breathing.

Our group has found that necropsies of euthanised pigs help to tell a story of the underlying conditions and allow a psychological justification that the work of euthanasia was required.

An integral factor to reduce stress includes supportive managers, owners and peers, allowing stockpersons the opportunity to examine stressful situations in a safe and confidential environment. Safe environments can only be achieved when there is an openness based on the culture and values of the employees and an exchange of ideas to ensure that the approaches adopted by the farms are relevant and accepted. As an industry, we communicate to consumers that “pig farmers care” – as farm managers we need to make sure that stockpeople know that “we care that you care.”

We must present humane euthanasia in a manner that is factual and sensitive. We (swine people) need to work to not only share our own concerns but also listen and address those of our colleagues and consumers. Just as the concepts of good animal welfare are never static; the swine industry is constantly collaborating and investigating new dynamic solutions to improve our knowledge and ability to best care for our pigs, including improved euthanasia techniques and support.

Conclusion

Despite their best efforts, stockpersons will encounter situations in which the best option for the pig is humane euthanasia. While industry-specific guidelines for humane euthanasia of swine do exist, the difficulty that a stockperson encounters lies in not only correctly identifying the compromised animal but also in deciding when and whether to treat or euthanize. We urge farmers to work with their veterinarian and employees to establish an on-farm euthanasia protocol for each phase of production to alleviate any questions or anxiety regarding proper euthanasia expectation. Several methods of euthanasia are available and accepted by the AVMA and AASV.

Each method is unique and specific for distinct ages and phases of production and ensures a humane end of life. We must also support further and continued research into hiring and keeping the best stockpeople and continuing to seek production practices that ensure their well-being as well as the pigs for which they provide care. Prosperity for all!

References

- Gemus, M. 2014. The Effect of Stockpeople on Pigs. (Last accessed February 5, 2015).

- Matthis, S. 2004. Selected Employee Attributes and Perceptions Regarding Methods and Animal Welfare Concerns Associated with Swine Euthanasia. (Last accessed February 5, 2015).

- Whiting, T. 2006. Future Trends in Animal Agriculture: Advancing Farm Animal Welfare and the Canadian Experience

- Festinger, L. 1957. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Stafford, K.J., McKelvey, K. and Budge, C. 1999. How does animal euthanasia affect people and how do they cope? Companion Animal Society Newsletter. 10: 7-14.

- Herzog, H.A., Vore, T.L., New, J.C. 1989. Conversations with veterinary students: Attitudes, ethics, and animals. Anthrozoos. 2:181-188.

- Gardner, D. 2014. Managing grief associated with euthanasia. (Last accessed February 6, 2015).

- Leiser, R. 2008. Coping with euthanasia. Downloaded 23 July 2008.

- On-farm euthanasia of swine. 2008. (Last accessed February 9, 2015).

- Sadler, Johnson and Millman. 2014. Alternative Euthanasia Methods to Manually Applied Blunt Force Trauma for Piglets Weighing Up To 12 lbs. Pork Information Gateway. November 2014. Bulletin pig 05-06-08.

- Casey-Trott T.M., Millman S.T., Lawlis P., Widowski T.M. 2010. A non-penetrating captive bolt (modified Zephyr) is effective for euthanasia of neonatal piglets. Proc Cong Int Pig Vet Soc. p1158.

- Casey-Trott, T.M., Millman S.T., Turner P.V., Nykamp S.G. and Widowksi T.M. 2013. Effectiveness of a nonpenetrating captive bolt for euthanasia of piglets less than three days of age. J. Anim. Sci. 91:5477-5484.

- Casey-Trott T.M., Millman S.T., Turner P.V., Nykamp S.G., Lawlis P., Widowski T.M. 2014. Effectiveness of a nonpenetrating captive bolt for euthanasia of 3kg to 9kg pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 92:5166-5174.

| Notes on Appendix 1 |

| The table illustrates suggested and accepted methods for humane euthanasia of swine. (N=none, L=low, M=medium, H=high). Regardless of the procedure, staff must be properly trained on the use of equipment, proper restraint, maintenance, safety and confirmation of insensibility and death. (*) – In some instances, the initial method may only stun the animal and second step such as exsanguination (bleeding out) or pithing (physical destruction of the spinal cord by a rod or cane) may be required to fully euthanise the animal. |

July 2015