Stunning at slaughter: is your hard work going to waste?

What are some of the stunning methods currently used at slaughter and how can an inefficient or inappropriate stunning technique result in carcass degradation and loss in earnings for the producer?Pigs are stunned prior to slaughter to minimise the suffering they experience. This is because an animal must be awake and conscious for poor welfare to occur, and an effective stun is one that renders the pig insensible for long enough for it to be stuck and bled without regaining consciousness. The two most common methods of stunning pigs are electrical and gas stunning, and there are advantages and disadvantages of each method for pig welfare and carcass quality.

Electrical stunning involves applying an electrical current to the head of the pig at a sufficient strength to overload the electrical impulses in the brain and cause the pig to become unconscious. The strength of the current, how long the current is applied for, and the placement of the electrodes (head only or head and body) will determine the effectiveness and duration of the stun. The minimum current needed to induce unconsciousness in pigs is 1.3A at 240V for 3 seconds. A higher intensity stun is associated with a longer period of unconsciousness, but also a decrease in carcass quality compared to gas stunning due to higher rates of blood splash (ecchymosis) and bone fractures.

The advantage of using electrical stunning is that it is quick to apply and provides an immediate stun, but it does have some disadvantages for pig welfare. Pigs must be stunned individually in a restraining device and this restraint and isolation from other pigs is very stressful for them. They may struggle violently, which makes it difficult to accurately apply the stunning equipment, and their acute stress response has negative consequences for meat quality. In addition, the equipment must be well maintained to ensure the electrical current is strong enough, and does not deliver pre-stun shocks to the animal.

Gas stunning involves exposing the pigs to carbon dioxide gas (CO2) at concentrations of 80% or more. The CO2 replaces the oxygen in their blood and causes the fluid around the brain to become acidic, resulting in a loss of consciousness within about 30 seconds. As with electrical stunning, this is a reversible stunning method and pigs can regain consciousness if left in fresh air. The equipment used for gas stunning means that pigs can be stunned in groups, and in some facilities the pigs can be loaded into the stunning chamber using automated gates, avoiding handling stress due to humans.

The advantage of gas stunning is that pigs can be stunned in groups with minimal handling and restraint, but this method comes with its disadvantages for pig welfare because it does not cause an immediate stun. In addition, breathing CO2 at concentrations higher than 30% is aversive for pigs. This is because CO2 forms an acid when it contacts wet surfaces, and may cause burning in the eyes and throats of exposed animals. Pigs will display avoidance behaviour, gasping and other indicators that they perceive the gas to be aversive.

Other methods of stunning are available, such as captive bolt methods or alternative types of gases, but these are not widely used for a variety of reasons. Captive bolt stunning requires the bolt to be placed in a precise position on the pig’s forehead to ensure it can penetrate the thick skull in this area, and this is difficult on a moving animal. As with electrical stunning, captive bolt stunning can result in violent kicking from the pig, which poses difficulties for handling post-stun. Exposure to alternative types of gases, such as argon or nitrogen, will cause pigs to lose unconsciousness by depriving them of oxygen. This stunning method results in fewer signs of distress than with CO2 stunning, but takes much longer for pigs to become unconscious (e.g. 30 secs with CO2 vs 3-5 mins with argon). This delay, combined with the higher cost of these gases, is not considered feasible under commercial conditions.

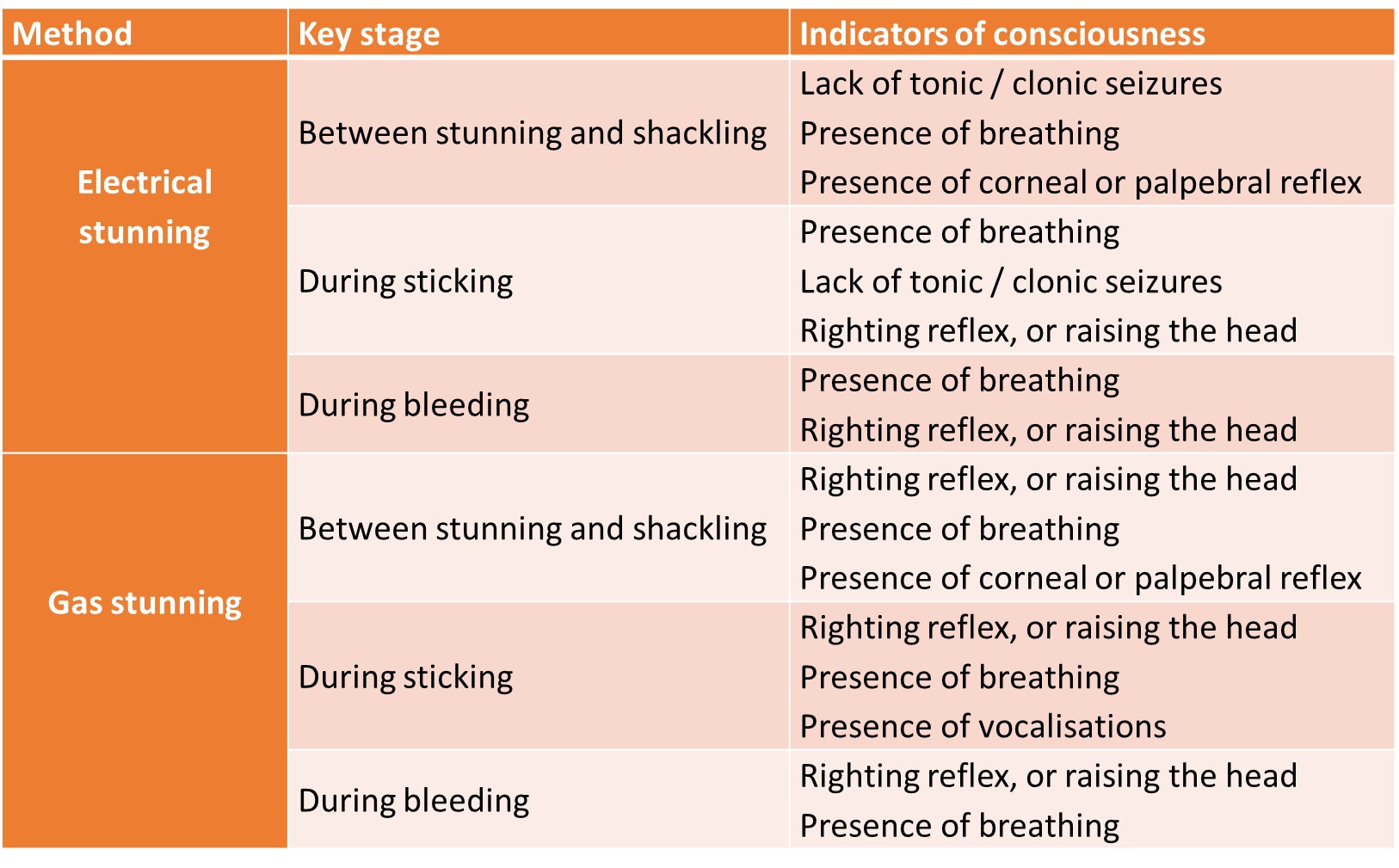

No matter which stunning method is used, it is imperative to ensure that the stun is effective. This means that the pig is rendered unconscious quickly and effectively with minimal suffering, and that the pig does not begin to regain consciousness before it has been bled out. The signs of a pig regaining consciousness differ between electrical and gas stunning, and a summary is presented in Table 1. If pigs begin to show any of these signs they must be re-stunned, and under no circumstances must sticking occur or carcass dressing continue until a successful re-stun been confirmed. Effective stuns can be ensured by the correct use of stunning equipment, the regular maintenance of this equipment, and by remaining vigilant to the signs of pigs regaining consciousness so that they can be re-stunned immediately.

Table 1. Indicators of pigs regaining consciousness following stunning (taken from Velarde and Dalmau (2018)).

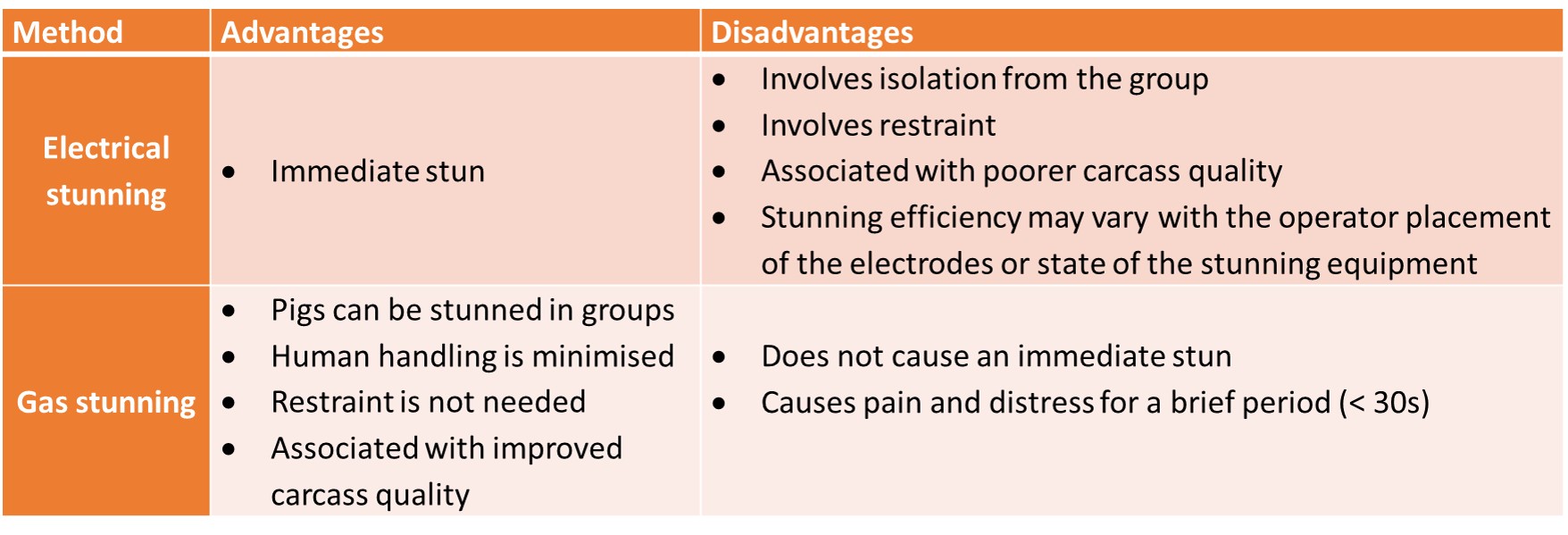

In conclusion, successful stunning is a vital component of ensuring that the slaughter process is as humane as possible, with the amount of suffering experienced by each animal minimised. Each method of stunning provides different advantages and challenges for pig welfare, as indicated in Table 2. CO2 stunning allows pigs to be stunned in groups, and is associated with better carcass quality due to a reduction in blood splash, bone fractures, PSE and drip loss. However, CO2 does not stun pigs immediately and is associated with signs of distress. More research is needed to develop new combinations of gases that can induce unconsciousness rapidly and with minimal signs of distress.

Table 2. Advantages and disadvantages of electrical and gas stunning methods for pig welfare.

For more information on this topic, please refer to Velarde and Dalmau (2018). ‘Chapter 10. Slaughter of Pigs’ in Advances in Pig Welfare.